I’ve spent the past year visiting memorials, monuments, museums, and concentration camps in Germany, exploring how that country remembers the Holocaust. I wanted to understand if there was anything the U.S. could learn. Here’s the story of what I found:

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

2/ When I was writing my book, How the Word Is Passed, I was thinking a lot about what public memory looked like in the US, specifically in the context of slavery. After the book came out I began thinking more about what public memory to past crimes looked like in other countries

3/ I was especially interested in thinking about Germany, a place that is often lifted up as an exemplar of remembrance for their willingness to acknowledge, confront, and build memorials to the Holocaust and the role that country played in perpetuating that horrific crime.

4/ I’d often invoke Germany myself, talking about their impressive commitment to memorialization. But then I had a moment where I realized that while I kept talking about how impressive Germany’s memorials were, I had never actually seen them for myself. I needed to change that

5/ So I went to Germany and visited memorials, monuments, museums, and historical sites tied to the history of the Holocaust. Here are some of the places that I went:

6/ I visited the House of the Wannsee Conference, an idyllic lakeside villa on the outskirts of Berlin, where, on January 20, 1942, the leaders of the Nazi regime discussed and drafted their ideas about how to implement “the final solution of the Jewish question.”

7/ I visited Gleis 17, the train station from which thousands of Jewish families were forced to get on trains (and pay for their own tickets) taking them to camps like Auschwitz. Today, it is a memorial that shows the number of Jewish people deported each day on the platform.

8/ I visited the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which sits in the center of downtown Berlin, spanning 200,000 sq feet and consisting of 2,711 concrete blocks. The space resembles a graveyard, a vast cascade of stone markers with no names or engravings on their facade.

9/ I visited the Topography of Terror museum, where people can learn about the history of the Nazi regime, and the way Hitler and the SS both gained and used their power. It’s located on the former grounds of the headquarters of the Gestapo.

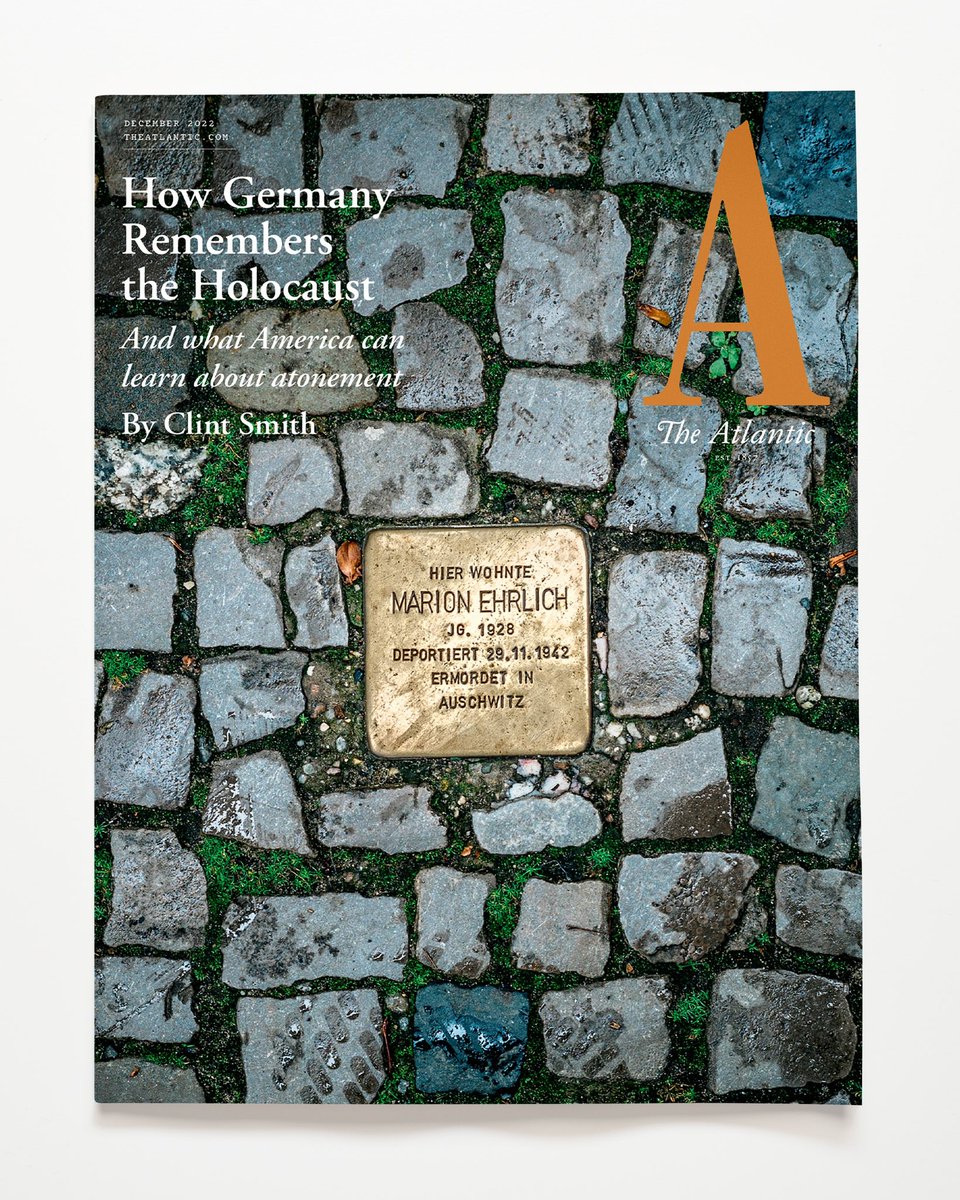

10/ I saw the Stolperstein, small brass “stumbling stones” that memorialize people who were victims of the Nazis. There are more than 90,000 stones in 30 European countries. The name, birthdate, and fate of each person are inscribed and placed in front of their final residence.

11/ I went to Dachau. Over the course of 12 yrs, over 41,000 people were killed there & in subcamps. Many were burned in the crematorium or buried, but thousands of corpses remained aboveground. When American soldiers liberated the camp & saw the bodies they vomited, they cried.

12/ I have stood in many places that carry a history of death—plantations, execution chambers—but I have never felt my chest get tight the way it did when I stood inside Dachau’s gas chamber. The ceiling was so low, you could reach up and touch it with your hands.

13/ I imagined the people who once stood in rooms like this one in death camps across Europe, the moment they realized what the holes in the ceiling were for. That it was not for a shower, but for gas. It is a fear I cannot fathom. It is a type of torture I cannot fully grasp.

14/ I learned so much from the people I spent time with, specifically Jewish people living in Germany who carry this history with them in the most personal and intimate ways. They are people who lost parents & grandparents in the Holocaust, & people who survived it themselves.

15/ One thing I learned that I had not fully understood, was how few Jewish people were left in Germany.

Jewish people represent *less than a quarter of a percent* of the population in Germany. There are more Jewish people in the city of Boston than there are in all of Germany

Jewish people represent *less than a quarter of a percent* of the population in Germany. There are more Jewish people in the city of Boston than there are in all of Germany

16/ One Jewish woman I spoke to said that this creates an environment in which Jewish people are more historical abstractions than they are actual people, empty canvases upon which Germans can paint their repentance. Many Germans do not personally know a Jewish person.

17/ This is a profound difference compared to the US, where there are still millions of Black people. There are a very different set of implications for memory here.

18/ I want to be clear that this piece is not meant to be any definitive account of Holocaust memorialization. Many brilliant people have wrestled with this question for years. It is simply meant to be a single meditation on a place that has taught me so much about remembrance.

19/ This piece is only possible because of the incredible editing of @denisewills & @AmyWeissMeyer. @JeffreyGoldberg supported this idea from the beginning & encouraged me to make the trip to Germany. The copy editors and fact checkers at the Atlantic are the best in the business

20/ I hope you’ll read the story. These trips to Germany changed me forever. The way they remember the Holocaust is endlessly fascinating, profound, and complex. I’ll be thinking about it for the rest of my life.

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

Also, not to be forgotten, the incredible photos above are by photographer Marc Wilson.

I also want to take a moment to say that this sort of story is only possible because of Atlantic subscribers. Your support provides the resources that make this possible. If you’re able, I hope you’ll consider subscribing so we can keep doing this work: accounts.theatlantic.com/products/?sour…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh