The small city of Lugo in northern Spain has a special secret.

It is the *only* place in the world to have a complete set of intact Roman walls. They were built 2,000 years ago and surround the entire old town.

But how did they survive? That's where it gets interesting...

It is the *only* place in the world to have a complete set of intact Roman walls. They were built 2,000 years ago and surround the entire old town.

But how did they survive? That's where it gets interesting...

The city of Lugo was originally founded as Lucus Augusti in 13 BC.

It was a vital outpost and so in the 3rd century AD the Romans built a huge defensive fortification around the city, over 2,000 metres long and up to 15 metres tall, with over 80 towers.

It was a vital outpost and so in the 3rd century AD the Romans built a huge defensive fortification around the city, over 2,000 metres long and up to 15 metres tall, with over 80 towers.

Even Rome itself, despite being swamped by ruins of every imaginable kind, does not have intact fortifications like Lugo.

Its Aurelian Walls, dating from the 3rd century AD, are rather more imposing and impressive.

But they survive in disconnected fragments:

Its Aurelian Walls, dating from the 3rd century AD, are rather more imposing and impressive.

But they survive in disconnected fragments:

And Hisarya in Bulgaria, once a Roman military stronghold in Thrace, has some incredibly impressive walls.

They survive at their original, intimidating height in parts, but are otherwise largely ruinous, and don't fully surround the city.

They survive at their original, intimidating height in parts, but are otherwise largely ruinous, and don't fully surround the city.

So why does Lugo still have this extraordinary circuit of walls - over two kilometres long - in such good condition?

It might have something to do with the materials from which they were built, of slate and shale rather than brick:

It might have something to do with the materials from which they were built, of slate and shale rather than brick:

But the truth is that, as you might suspect, they're not *completely* original.

Over the centuries these great walls have been restored, renovated, and tampered with many times.

Consider the gates. Some of the original Roman gates survive (five in all) like the Porta Mina:

Over the centuries these great walls have been restored, renovated, and tampered with many times.

Consider the gates. Some of the original Roman gates survive (five in all) like the Porta Mina:

While five larger gates were added in the 19th century as the city of Lugo grew in size and more gates were needed for traffic and pedestrian circulation.

Like the Bishop's Gate:

Like the Bishop's Gate:

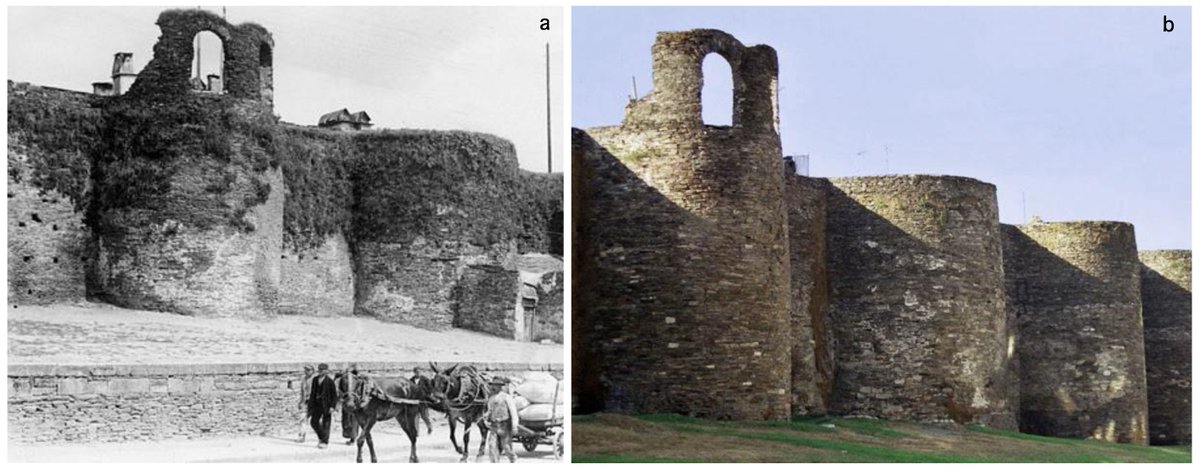

And since the 19th century consistent efforts have been made to restore them, not limited to removing overgrowth (as below) but including more invasive work to rebuild damaged sections.

This has continued through the 20th and into the 21st century - an ongoing municipal project.

This has continued through the 20th and into the 21st century - an ongoing municipal project.

Which is part of the reason for their most striking feature (beyond the overall quality of their condition): this spacious walkway running along their entirety.

It's not really an original Roman feature, but its creation has given the city something utterly unique.

It's not really an original Roman feature, but its creation has given the city something utterly unique.

And so this touches on one of the most interesting debates in the realms of history, architecture, and archaeology: restoration v preservation.

Should we preserve ruins as they are, to prevent further degradation, or restore them to how they once looked?

Should we preserve ruins as they are, to prevent further degradation, or restore them to how they once looked?

This debate really kicked off in the 1800s.

On one side were those like the scholar and artist John Ruskin (1819-1900) who believed that all buildings, not only ruins, should be left exactly as they are.

On one side were those like the scholar and artist John Ruskin (1819-1900) who believed that all buildings, not only ruins, should be left exactly as they are.

He belived that a building's age was its truest quality, and that restoration was "as impossible as raising the living from the dead."

And therefore that "no restoration should ever be attempted, otherwise than... in the sense of preservation from further injuries."

And therefore that "no restoration should ever be attempted, otherwise than... in the sense of preservation from further injuries."

Ruskin's position was at least partially related to the wave of restoration in 19th century Britain.

There was a boom in church attendance and so the Victorians set about restoring all those old Medieval churches, ensuring they were fit for purpose.

There was a boom in church attendance and so the Victorians set about restoring all those old Medieval churches, ensuring they were fit for purpose.

But their restorations were often more like renovations, either totally unsympathetic to the original (rather like St. Alban's Cathedral, below) or sometimes more like overly sentimental, inauthentic rebuilds.

It was this sort of thing that Ruskin found so troublesome.

It was this sort of thing that Ruskin found so troublesome.

While French architect Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) embodied the other side of the debate.

He was the foremost restorer of his age, and took on projects all around France, like the Notre Dame.

Under his guise it was, after significant work, restored to its Medieval glory.

He was the foremost restorer of his age, and took on projects all around France, like the Notre Dame.

Under his guise it was, after significant work, restored to its Medieval glory.

He also rebuilt the original Medieval spire (or fleche) of the Notre Dame, which had been taken down in the 1700s.

His version, which burnt down in 2019, was slightly different to the original.

Does that make the Notre Dame inauthentic?

His version, which burnt down in 2019, was slightly different to the original.

Does that make the Notre Dame inauthentic?

One of Viollet-le-Duc's greatest successes was the restoration of Carcasonne, a Medieval citadel in southern France.

The local government had decided to demolish its walls but, thanks to public outcry, Viollet-le-Duc was tasked with their complete restoration.

The local government had decided to demolish its walls but, thanks to public outcry, Viollet-le-Duc was tasked with their complete restoration.

Throughout the 20th century both approaches have been adopted.

For example, the Ba'athist regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq started (but did not finish) a total restoration of the Ziggurat of Ur, a three thousand year old Sumerian temple.

For example, the Ba'athist regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq started (but did not finish) a total restoration of the Ziggurat of Ur, a three thousand year old Sumerian temple.

But it's more common to leave ruins as they are, performing structural repairs at most to prevent them from totally falling apart.

Not just for famous monuments like the Parthenon - whose restoration seems unthinkable - but even for much smaller, locally-significant ruins.

Not just for famous monuments like the Parthenon - whose restoration seems unthinkable - but even for much smaller, locally-significant ruins.

And yet the restored walls of Lugo have given the people of the city something truly special.

They are an object of civic pride and, though a part of Lugo's ancient history, are still very much alive and in use; people go for walks and runs on them, or just hang around there.

They are an object of civic pride and, though a part of Lugo's ancient history, are still very much alive and in use; people go for walks and runs on them, or just hang around there.

Another interesting result of Lugo's maintained wall is the way it creates a real city centre, now largely pedestrianised, with narrow streets and great mixed-use spaces.

Regulations to limit the height of buldings and potentially damaging construction work have furthered this.

Regulations to limit the height of buldings and potentially damaging construction work have furthered this.

Which brings us to something else about Lugo's wonderful Roman walls.

Even if they have been restored and well-maintained, that doesn't tell the full story of their survival; it is at least partially thanks to simple preservation that they remain...

Even if they have been restored and well-maintained, that doesn't tell the full story of their survival; it is at least partially thanks to simple preservation that they remain...

Because most European cities had walls and fortifications of some kind, whether Roman or Medieval.

But, in the 19th century particularly, they were deemed subsidiary to the demands of urban expansion and accordingly demolished.

Not Lugo - those new gates were a middle ground.

But, in the 19th century particularly, they were deemed subsidiary to the demands of urban expansion and accordingly demolished.

Not Lugo - those new gates were a middle ground.

The City of London was once surrounded by a Roman wall which had been further fortified in the Middle Ages.

But as its defensive purpose disappeared and London's population expanded, the wall was largely demolished, leaving only scattered fragments hidden around the city.

But as its defensive purpose disappeared and London's population expanded, the wall was largely demolished, leaving only scattered fragments hidden around the city.

And so they are the Roman walls of Lugo.

A story of restoration versus preservation, and of preservation versus demolition; of history as a still-living, still-useful part of civic life, or as a simple ruin.

To restore or to preserve? Lugo offers one potential answer.

A story of restoration versus preservation, and of preservation versus demolition; of history as a still-living, still-useful part of civic life, or as a simple ruin.

To restore or to preserve? Lugo offers one potential answer.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh