Just finished #EmergencyState & some thoughts.

I really enjoyed it, & it’s a real feat managing to distill so much in such an accessible, readable & intellectually wide-ranging way. I hope he writes more books along these lines.

I really enjoyed it, & it’s a real feat managing to distill so much in such an accessible, readable & intellectually wide-ranging way. I hope he writes more books along these lines.

My particular interest is in one theme in the book: why were such draconian laws given so little scrutiny, even taking account of the emergency conditions? Hence, partly at least, why much of it was so poor, & misunderstood, including by the police & Government itself.

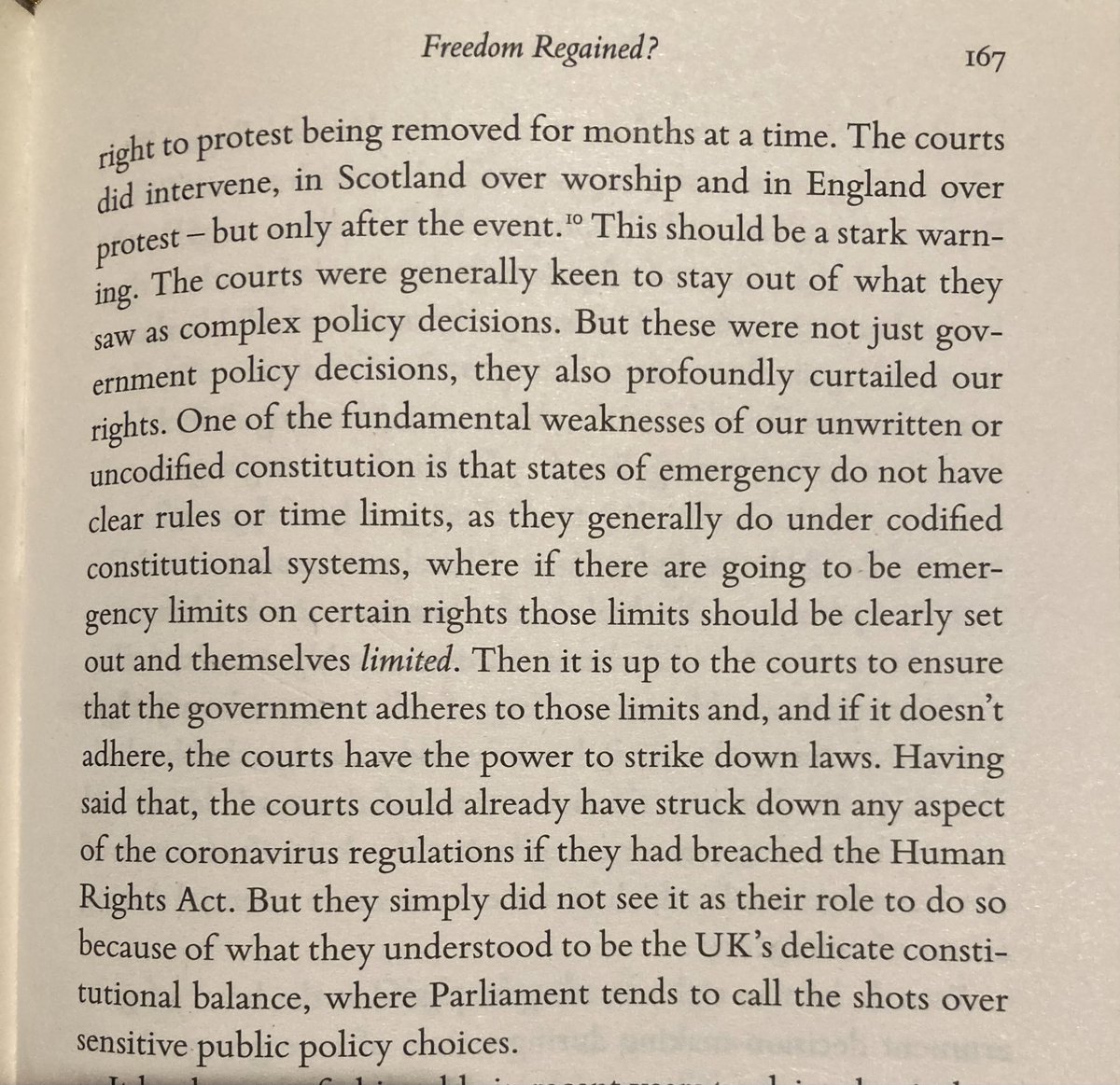

A key reason is suggested in the conclusion: fundamental constitutional defects, in particular the lack of a codified constitution. But what is the evidence for that?

There’s a good summary of previous measures taken to tackle emergencies, & I’d’ve liked more on legislative history & expectations. EG Defoe’s book on the plague suggests that 2ndry legislation under an old Act was also used as far back as the 17th century (extract below).

IE I wondered whether this was a sort of default position for the UK, which, perhaps, our constitution encourages? Or was the Government’s response actually out of the ordinary, & more to do with the characters & circumstances concerned?

And how did the UK compare to other countries on democratic scrutiny? EG did those with codified constitutions provide more scrutiny?

Perhaps more on that may be needed to answer definitively whether there’s a systemic explanation.

Perhaps more on that may be needed to answer definitively whether there’s a systemic explanation.

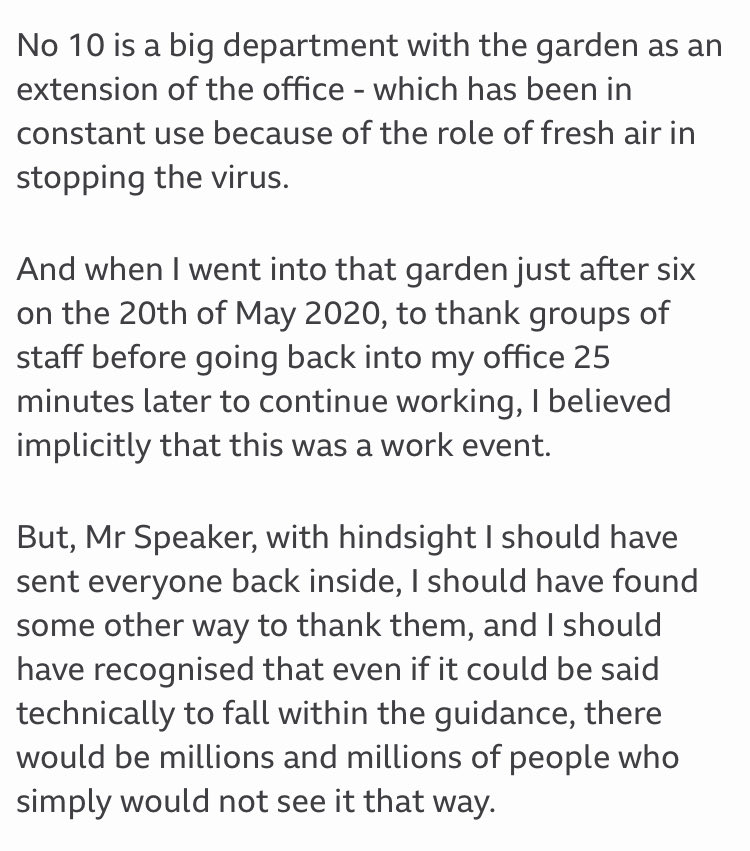

Elsewhere the book considers that the attitude of the particular Government at the time was to some extent a key factor.

This looked a stronger (& perhaps easier) argument to me.

This looked a stronger (& perhaps easier) argument to me.

As I’ve argued in this thread, parliamentary democracy has been under assault on (at least) two fronts recently. The Conservatives even won power in 2019 with a manifesto openly boasting that its leader defies Parliament.

https://twitter.com/inkspringed/status/1587782613384699904

Does such a Government particularly thrive in a constitution like ours? Are its anti-democratic tendencies are exacerbated by it?

A counter-argument might say constitutions like that of the US aren’t immune either.

A counter-argument might say constitutions like that of the US aren’t immune either.

The book is IMV rightly sceptical whether cases like Dolan were correctly decided, & wonders whether courts buckled under pressure. But how can we be confident courts under a different constitution would have decided them differently?

So I think the book raises valid points & important questions here without necessarily providing enough to justify the conclusion that the constitution is at fault.

But that doesn’t at all detract from an excellent read & a hugely impressive intellectual achievement.

But that doesn’t at all detract from an excellent read & a hugely impressive intellectual achievement.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh