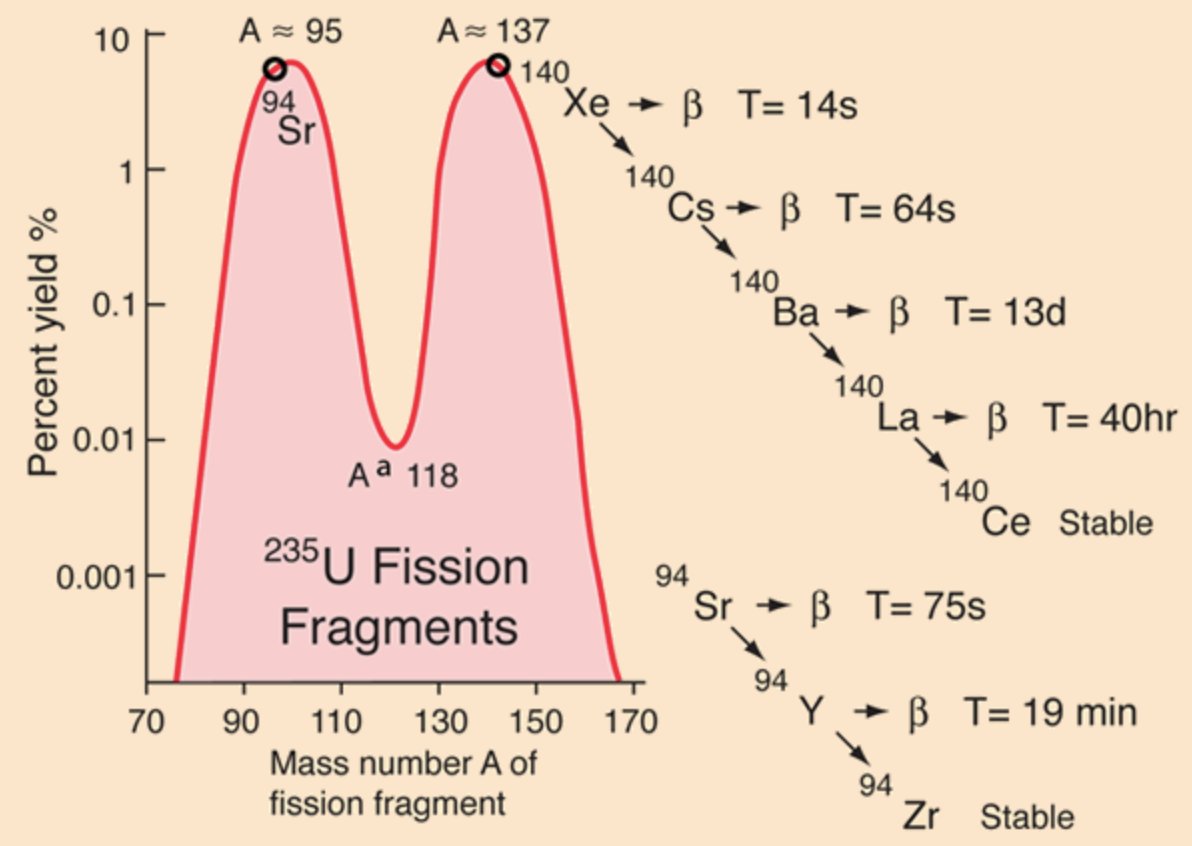

So when talking about recycling spent nuclear fuel (i.e. "waste"), we often like to focus on turning it back into more nuclear since that is an amazing trick! But there are also lots of useful isotopes to recover and if we recycle at scale it could really change things! 🧵 1/17

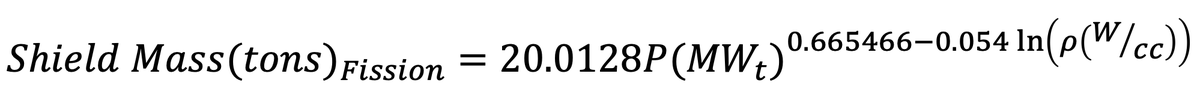

When atoms fissions, we get a broad range of isotopes with most of them massing either ~95 or ~137 amu, but there is a broad distribution and the exact make-up depends on isotope and neutron energy. 2/17 hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/NucEne/f…

The first obvious isotopes to recover are the ones we already do at research reactors, medical isotopes! Mo-99 is the most common fission fragment recovered, and it is used as a source of Tc-99m for medical diagnostics. I personally have even had some! 3/17

~6% of fissions make Mo-99, but it has a ~66 hr half-life so recovery is hard to do. Wide scale reprocessing would increase total supply, but the amount would vary. Other, longer lived isotopes will be available in larger amounts though! 4/17

Cs-137 also is made ~6% of the time and has a ~30 yr half-life. As a powerful gamma and beta emitter it has a number of uses in medicine and industry. Similar story for Sr-90, which has even been used as a much cheaper isotope for RTGs! Imagine low(er) cost space probes! 5/17

There also may be industrial applications for lower activity radionuclides like Tc-99 and Zr-93. Tc-99 doped steel is much more corrosion resistant and could be used in nuclear applications without any radiation concerns. 6/17

The Zr-93 generated as well as the leftover activated Zr clad from spent fuel could also be remade into slightly radioactive fresh clad for the recycled nuclear fuel. The industrial processing would be slightly more complex, but it would lower our waste burden. 7/17

But there are also stable isotopes to be recovered, and valuable ones at that! We can recover platinum group elements as well as some noble gases from fission products. Some may need some isotope separation, but others come out effectively ready to use! 8/17

Ruthenium is a very rare metal of which several isotopes are made during fission. The longest lived radioactive isotope is ~100 days, so after a couple years of "cooling" you would get pure, stable Ru for sale! Since it costs ~$475/oz that could be nice! 9/17

Rhodium is similar to Ru, but only has two isotopes and would be non-radioactive after ~10 days! It currently costs >$13000/oz so even tiny amounts are worth extracting! 10/17

Palladium is something many of us may be wearing, but it is a bit harder to justify extracting from fission. Although the yields are good (>0.1%) one of the 6 isotopes has a 6.5E6 yr half-life... Perhaps with good isotope enrichment we can make this make sense! 11/17

We also can extract good old fashioned silver while doing this, and all of it will be stable after just a couple weeks! This would only make sense when extracting the other platinoids though. Yttrium (not a platinoid, but a valuable rare earth) can also be extracted stable. 12/17

Indium can also be extracted, although it is technically radioactive. In-115 is one of the two "stable" isotopes found in natural indium though, and has a half-life longer than the age of the universe. Indium is some very valuable stuff, so I would think hard about this! 13/17

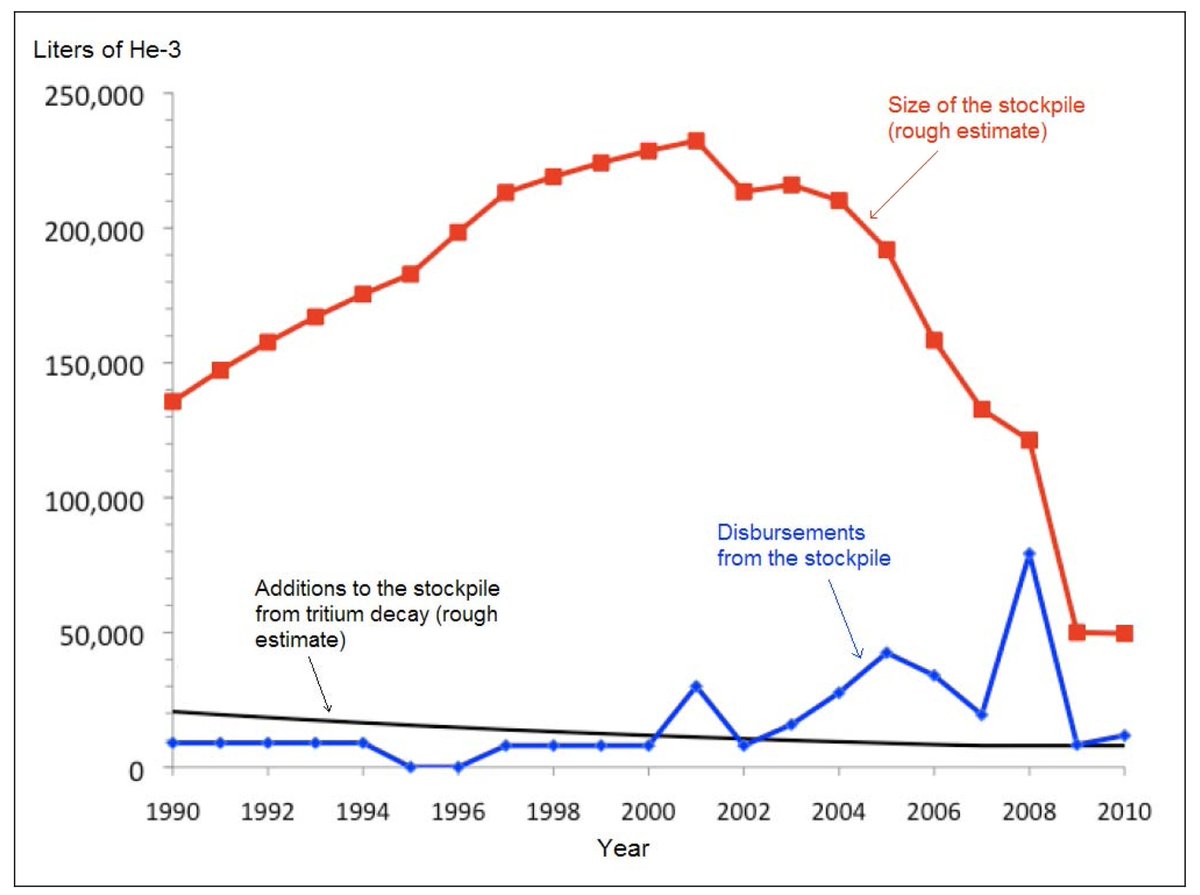

The final thing worth considering would be xenon and krypton. Xe will come out essentially stable, with one isotope technically being radioactive, but so long as to not matter. Kr will need some significant cooling (decades) or we could enrich it. Both are very expensive! 14/17

The various amounts of material recoverable will depend on burn-up, but recovery of some of these stable isotopes has been considered! A group from Russia looked into this and generated the following chart. 15/17

The total production just from current SNF is something worth considering. A future with more nuclear power would make this process even more exciting! We could potentially upend the platinoid and noble gas markets with enough reprocessing as well as lower the total cost. 16/17

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh