Variation theory is a powertool for building understanding in the classroom. But many teachers have never even heard of it.

Here's what variation is and how to use it:

↓

Here's what variation is and how to use it:

↓

A big part of the work of teachers involves helping pupils build an accurate understanding of abstract concepts.

Ideas such as proportion, power, and prefixes.

Ideas such as proportion, power, and prefixes.

However, new knowledge must be fashioned with existing.

"We understand new things in the context of things we already know."—@DTWillingham

And so, one of the best ways to build abstract understanding is by providing students with a range of concrete examples.

"We understand new things in the context of things we already know."—@DTWillingham

And so, one of the best ways to build abstract understanding is by providing students with a range of concrete examples.

The examples we choose and the variation between them has a big impact on the precision of resulting understanding.

This is the basis of 'variation theory'.

This is the basis of 'variation theory'.

Tell me more...

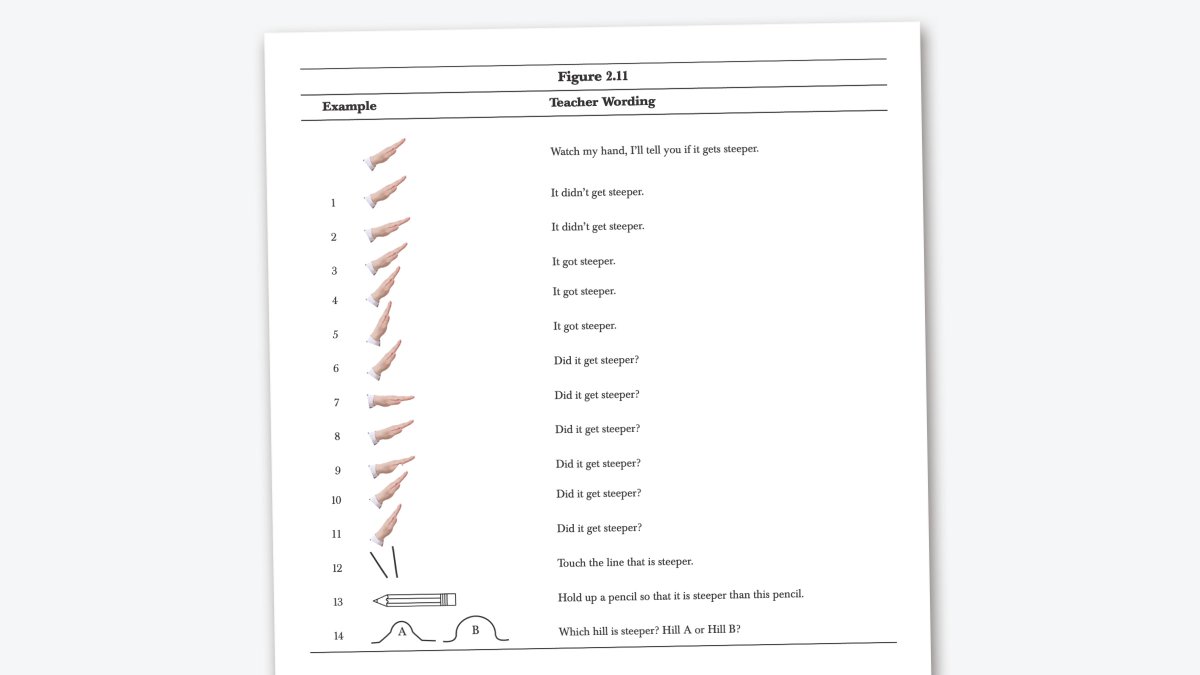

Essentially, when we present students with a contrasting range of examples—where some features change and others remain the same—we can draw their attention to the defining features of an concept.

And in doing so: sharpen their understanding.

Essentially, when we present students with a contrasting range of examples—where some features change and others remain the same—we can draw their attention to the defining features of an concept.

And in doing so: sharpen their understanding.

One of the key premises of variation theory is that students benefit from not only seeing examples of the thing, but also from examples that are *not* the thing.

These are called negative or non-examples.

This is getting pretty abstract, so let's consider an example 🤪

These are called negative or non-examples.

This is getting pretty abstract, so let's consider an example 🤪

EXAMPLE

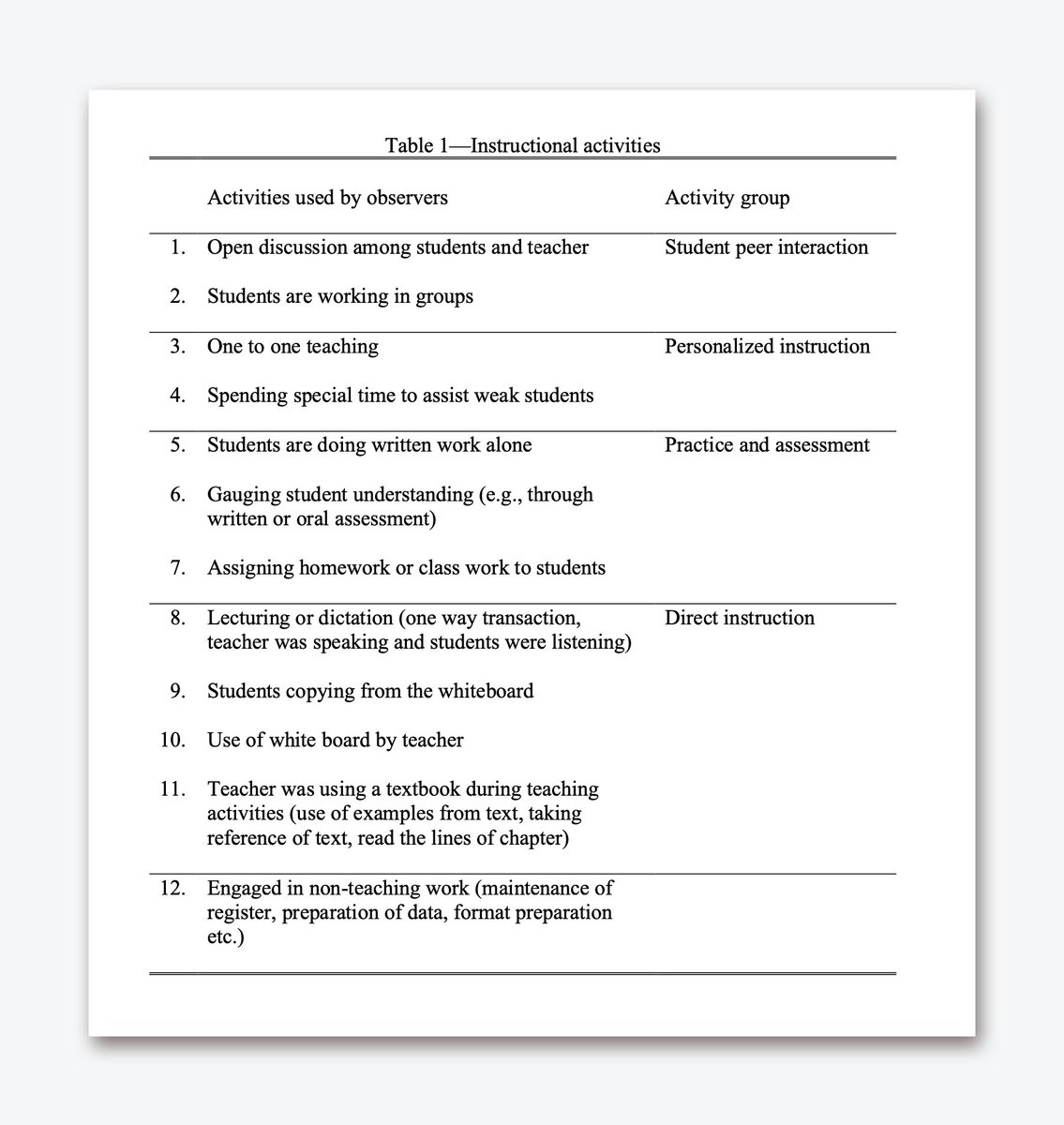

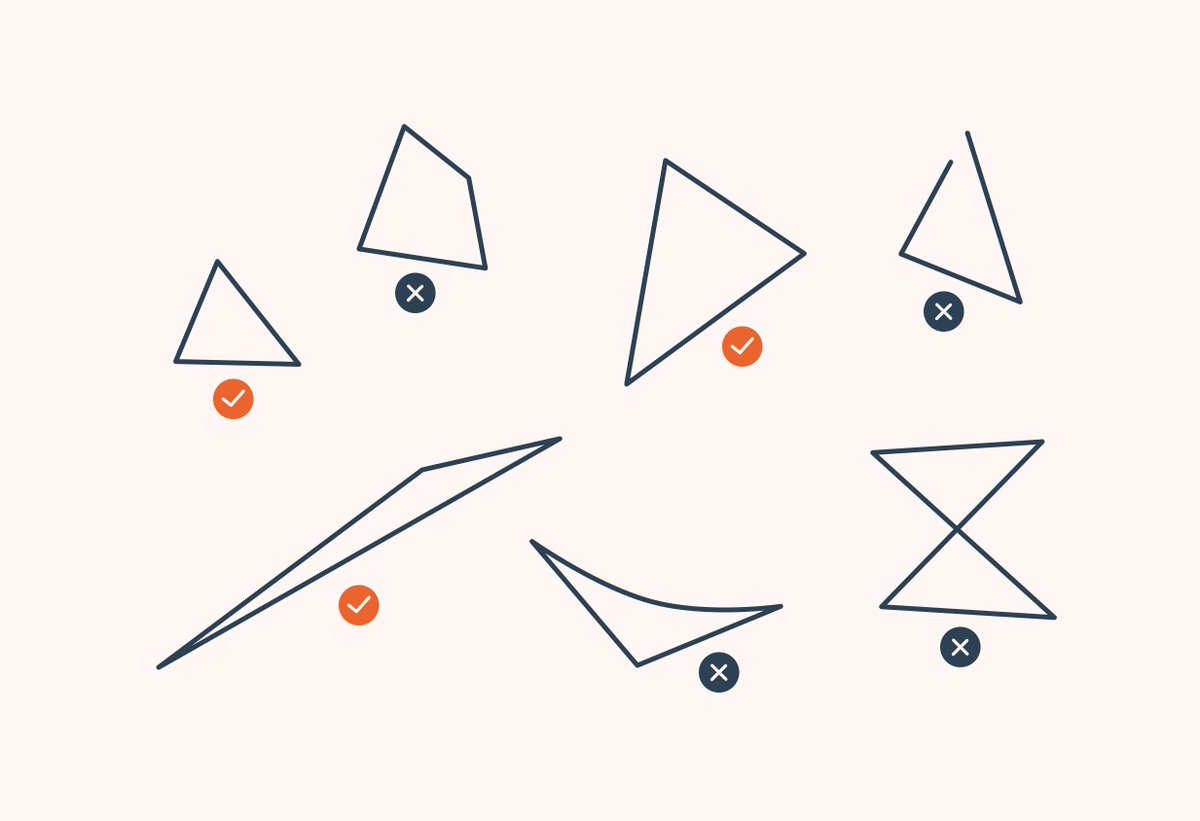

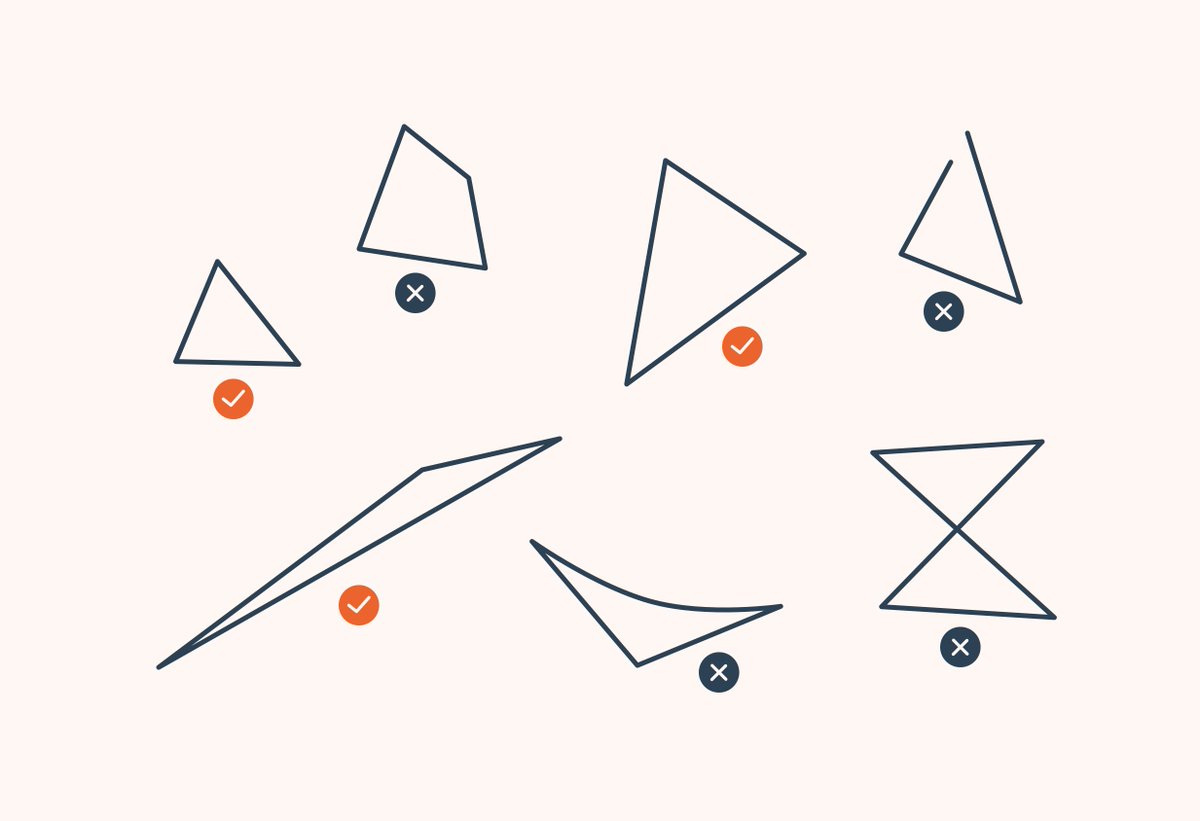

To help a student refine their understanding of a triangle, we might begin by establishing the defining and the non-defining features of the concept:

Defining → 3-sides, straight sides, closed shape

Non-defining → Length of sides, similarity of angles, orientation

To help a student refine their understanding of a triangle, we might begin by establishing the defining and the non-defining features of the concept:

Defining → 3-sides, straight sides, closed shape

Non-defining → Length of sides, similarity of angles, orientation

Then we'd present them with a range of examples, some positive and some negative.

Positive examples → shapes that *are* a triangle

Positive examples → shapes that *aren't* a triangle

Negative examples mitigate overgeneralisation.

Positive examples → shapes that *are* a triangle

Positive examples → shapes that *aren't* a triangle

Negative examples mitigate overgeneralisation.

ADVANCED TACTICS

To begin with, we provide examples that clearly *are* and *are not* triangles—far positive & negative examples.

But then we can progress to examples which are are less clear cut—near positive & negative examples.

To begin with, we provide examples that clearly *are* and *are not* triangles—far positive & negative examples.

But then we can progress to examples which are are less clear cut—near positive & negative examples.

This helps students better perceive the 'boundary condition' of a concept—when a thing ceases to become a thing.

Such as how far we can change a triangle before it stops being a triangle.

Near examples drive even greater precision in student understanding.

Such as how far we can change a triangle before it stops being a triangle.

Near examples drive even greater precision in student understanding.

VARIATIONS ON VARIATION

The triangle example outlined here illustrates just one of several ways to employ variation.

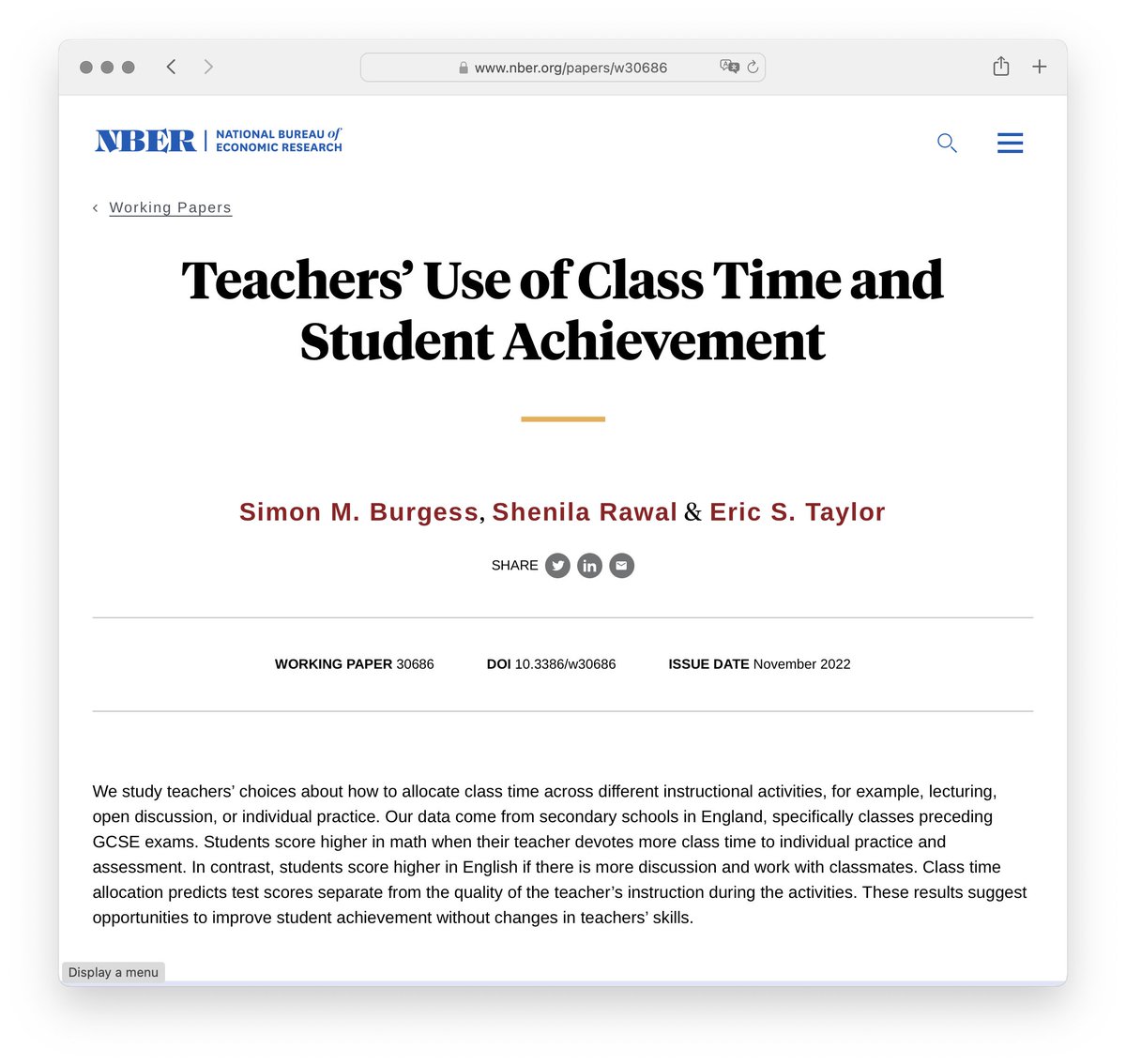

Depending on the subject being studied and prior student knowledge, there are 3 different approaches we might consider using:

The triangle example outlined here illustrates just one of several ways to employ variation.

Depending on the subject being studied and prior student knowledge, there are 3 different approaches we might consider using:

1/ Conceptual variation

→ Presenting examples and non-examples to refine the understanding of a particular idea (as in triangle example above).

→ Presenting examples and non-examples to refine the understanding of a particular idea (as in triangle example above).

2/ Relational variation

→ Illustrating how changing one variable impacts another, to build the understanding of a relationship.

→ Illustrating how changing one variable impacts another, to build the understanding of a relationship.

3/ Contextual variation

→ Experiencing the concept or its application in different guises or environments. This helps detach a concept form the context in which it has been learnt, and so promote transfer.

→ Experiencing the concept or its application in different guises or environments. This helps detach a concept form the context in which it has been learnt, and so promote transfer.

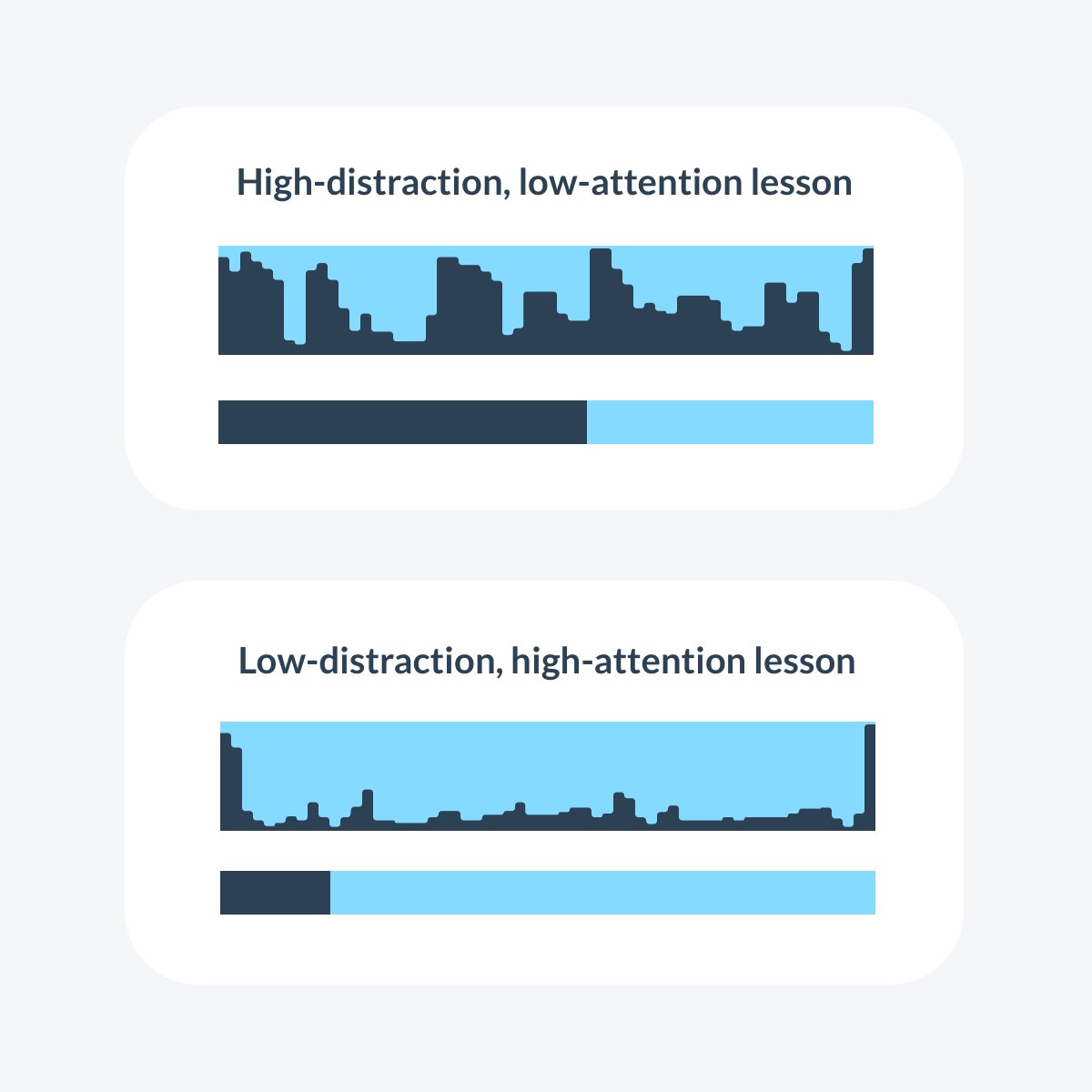

The key to variation is helping students attend to difference amongst similarity.

However, perceiving differences can be hard, particularly for novices.

Where possible, make it easier for your students to 'spot the difference' by presenting examples side-by-side.

However, perceiving differences can be hard, particularly for novices.

Where possible, make it easier for your students to 'spot the difference' by presenting examples side-by-side.

IMPORTANT

Variation is about drawing attention to specific features of an idea. This can only happen if we keep our changes minimal.

Exemplification quickly loses power if we change too many things at once.

Variation is about drawing attention to specific features of an idea. This can only happen if we keep our changes minimal.

Exemplification quickly loses power if we change too many things at once.

NOTE

The example I've provided here is for mathematics.

But variation theory has utility for any subject that aims to build abstract ideas.

The example I've provided here is for mathematics.

But variation theory has utility for any subject that aims to build abstract ideas.

For a wider range of examples across different subjects, grab a copy of:

📚How to Explain Absolutely Anything to Absolutely Anyone by @atharby

A fab resource for any teacher seeking to elevate their approach to explanation.

📚How to Explain Absolutely Anything to Absolutely Anyone by @atharby

A fab resource for any teacher seeking to elevate their approach to explanation.

For more on the underlying theory, check out:

🎓Variation Theory and the Improvement of Teaching and Learning by Mun Ling Lo

An epic read that goes crazy deep on curriculum & instruction. One of my fav papers of all time.

🎓Variation Theory and the Improvement of Teaching and Learning by Mun Ling Lo

An epic read that goes crazy deep on curriculum & instruction. One of my fav papers of all time.

And if you really want to go down the rabbit hole, get your eyes on:

🎓Theory of Instruction: Principles and Applications, by Engelmann & Carnine

One of the most comprehensive—albeit impenetrable—analyses of precision teaching ever conducted.

🎓Theory of Instruction: Principles and Applications, by Engelmann & Carnine

One of the most comprehensive—albeit impenetrable—analyses of precision teaching ever conducted.

So there you go, a brief introduction to variation theory and how it can help build abstract understanding in the classroom.

You probably do a lot of this already, but hopefully this helps refine *your* understanding further ;)

👊

You probably do a lot of this already, but hopefully this helps refine *your* understanding further ;)

👊

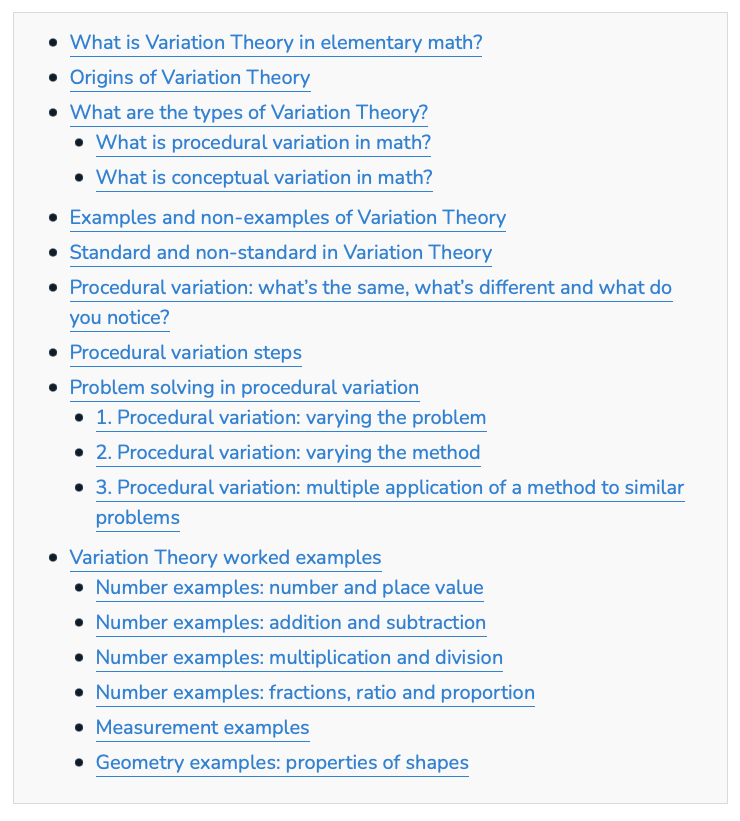

+ a great deep dive on variation theory for primary math(s) teachers from @Mr_AlmondED

thirdspacelearning.com/us/blog/variat…

thirdspacelearning.com/us/blog/variat…

+ helpful lethal mutation flag RE VT inefficiency in science (and probably beyond) from @adamboxer1

https://twitter.com/adamboxer1/status/1602233660811448320

@naveenfrizvi + interesting paper exploring how primary teachers learned about VT through lesson study, from @SmartJacques & @AliClarkWilson

discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1010…

discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1010…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh