1/This is a thread about metallurgy's secret cheat code, and how it's used by the aerospace industry to accomplish things that no material should.

In particular, how that cheat code is enabled on the humble, but amazing, jet engine turbine blade.

In particular, how that cheat code is enabled on the humble, but amazing, jet engine turbine blade.

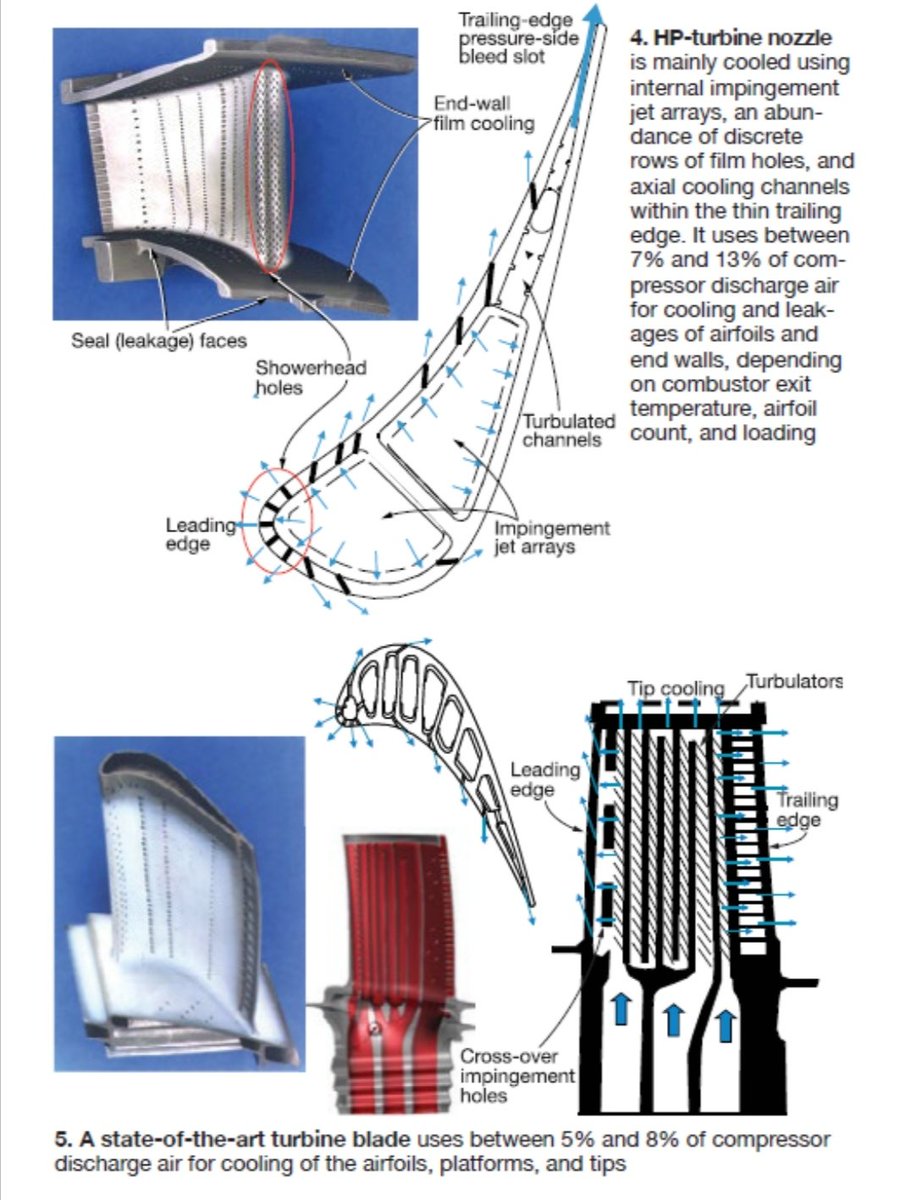

2/This is our friend, the high pressure turbine blade. It lives inside your everyday turbofan engine and helps you go on holiday. It also casually takes 20,000G of force and operates about 200C above it's own melting point.

I have a separate thread about that, but I digress.

I have a separate thread about that, but I digress.

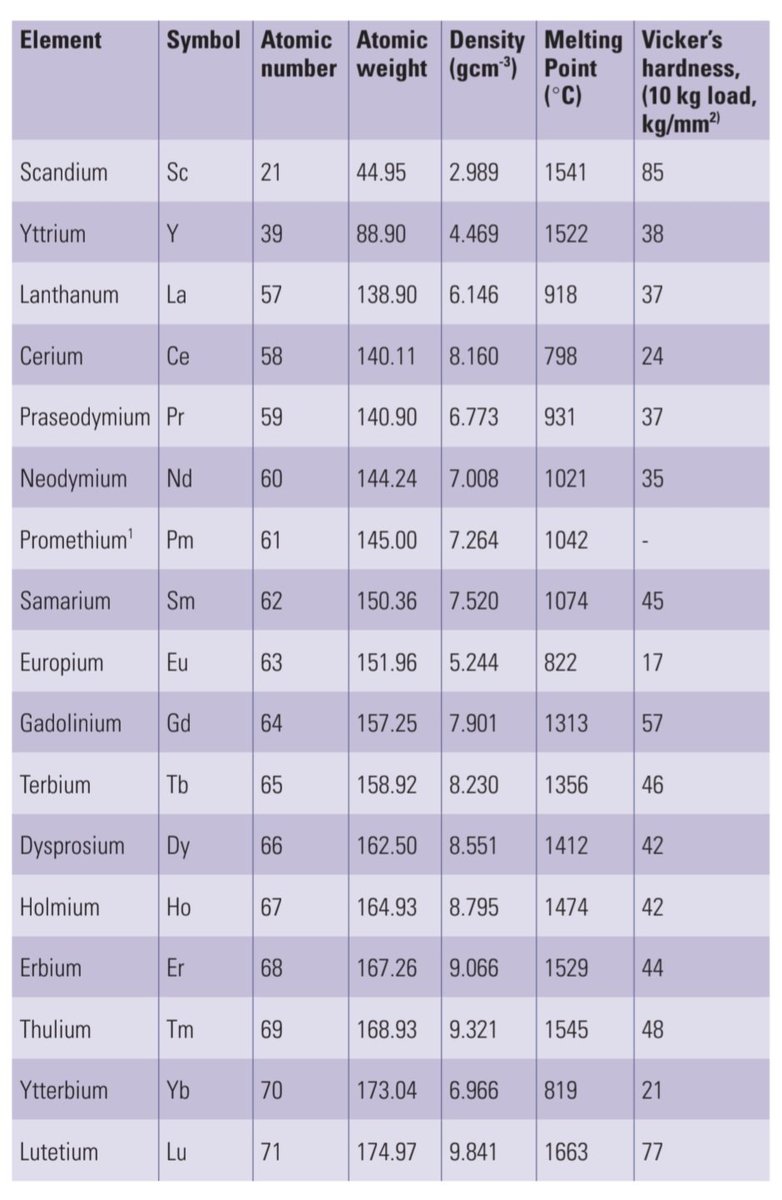

3/Zoom into any metal, real close-like, and you'll see this. Countless tiny crystals, forming a complex grain structure. The size and uniformity of these grains has a *huge* effect on the tensile strength and fatigue life of the material.

4/When the metal is casted it cools from a molten state, but it doesn't do so uniformly. Tiny crystals form and grow as the metal cools and solidifies. The size and uniformity of the crystals is dictated by the speed and uniformity of the cooling.

5/Broadly speaking the smaller the grain size, the better. Grain boundaries inhibit crack propagation and so the more of them there are, and the more uniform there are, the harder it is for defects to propagate. In a turbine blade, subject to insane stress, this is crucial.

6/Except there is an exception. At very high temperatures, thermal creep starts to become an issue which can dominate over cold tensile strength. For a blade operating right next to it's melting point this is a big deal.

Creep is enhanced by grain boundaries. What to do?

Creep is enhanced by grain boundaries. What to do?

7/With this exception comes a countermeasure. A cheat code if you will. Rather than small or large crystals, why not a single crystal with no grain boundaries at all? Not perfect for fatigue, but ideal for continuous load at high temperature.

Well, easier said than done.

Well, easier said than done.

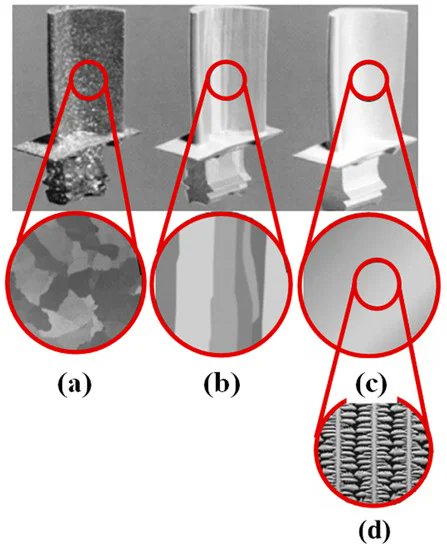

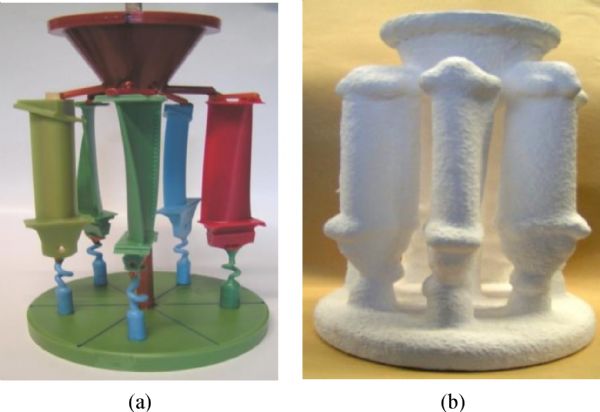

8/Enter the strange world of single crystal investment casting. First a wax turbine blade is produced, with a ceramic core inside held in place with platinum wires.

9/Then a robotic arm dips it repeatedly in ceramic slurry, which dries to create a ceramic mould (the wax will later be melted out). This is the mould that will enter the vacuum furnace and cast the Nickel superalloy.

10/The ceramic mould, filled with molten Nickel superalloy, is lowered from the vacuum furnace onto a chiller plate. This forces crystallisation to start from a single point.

11/The crystals move up through the mould as it is lowered slowly from the furnace. They move through a tight 'pigtail' which causes one crystal to dominate before it enters the rest of the mould. The pigtail is then removed.

12/The casting is removed from the mould and the core leached out. It is cleaned and etched to reveal the crystal structure for inspection, to ensure that impurities haven't caused multiple crystals to form that would threaten blade integrity.

13/The blade is the barrelled for a super polished finish and sent to turbine blade machining, leaving the foundry. After much additional processing, coating & inspection the blade is finished. A literal crystalline jewel, ready to take you overseas.

More fun engineering threads:

New & upcoming gas turbine trends:

The open-rotor engine:

Turbine blade film cooling:

Tidal energy basics:

New & upcoming gas turbine trends:

https://twitter.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1603766611470581760?t=wKYdzJP7WKB1F2iAJd9jVQ&s=19

The open-rotor engine:

https://twitter.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1594005868852514816?t=_qkxlWWwqZmMnERqaAq6wA&s=19

Turbine blade film cooling:

https://twitter.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1596473208487956480?t=74armmuqh1nKB31cYUvkGw&s=19

Tidal energy basics:

https://twitter.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1598247533310279681?t=QnOme_huZWtw5Yd4NGII-A&s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh