🥳Publication day for #UndergroundMathematics! Thanks to everyone involved❤️

Here’s a short🧵to its main argument: How did practical mathematics and a culture of accuracy developed in EM Europe? Rationality wasn’t just about scholars, it included craftsmen and artisans too!

Here’s a short🧵to its main argument: How did practical mathematics and a culture of accuracy developed in EM Europe? Rationality wasn’t just about scholars, it included craftsmen and artisans too!

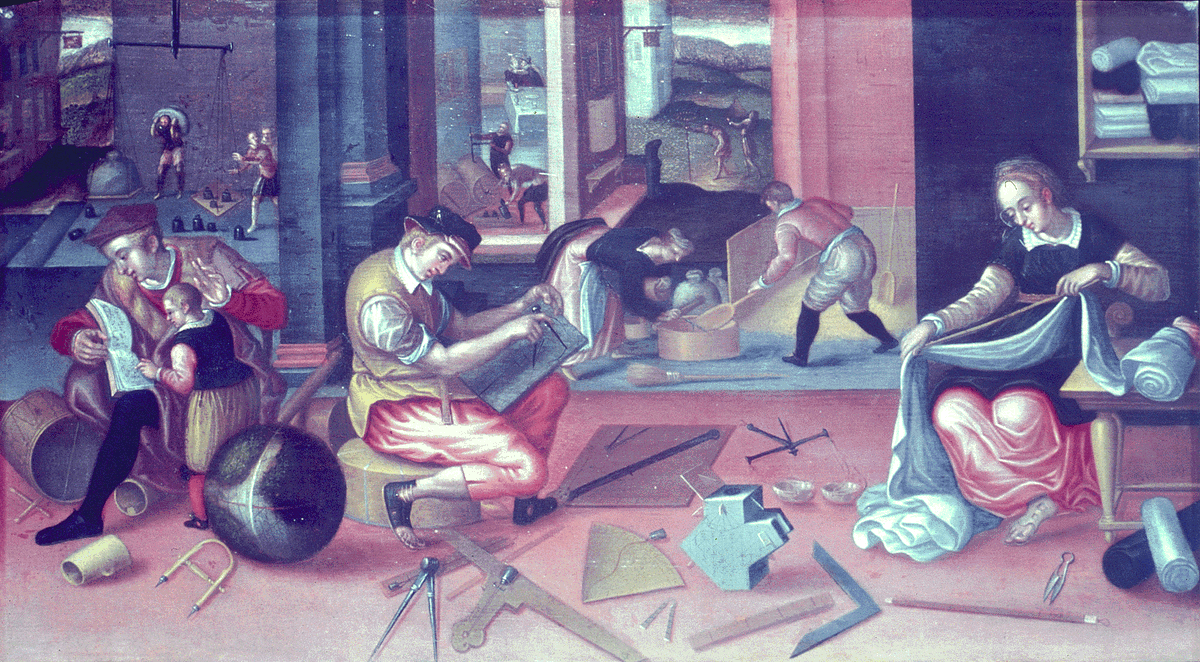

Practical mathematics was ubiquitous, from wine gauging to mercantile arithmetic. It was widely depicted, as here in ‘The Measurers’ (see Jim Bennett’s great piece on this painting @HSMOxford). And yet, usual narratives have forgotten a whole discipline: subterranean geometry!

The Geometria Subterranea was also known as Markscheidekunst or ‘the art of setting limits’. These surveyors were working underground in the silver mines of the Empire, in Scandinavia and Spain, but who knows what their mathematics was? Or how it was taught and improved?

Virtually forgotten today, subterranean geometry was once a big deal! Christian Wolff put it on the title page of his Mathematisches Lexicon, Leibniz took careful notes on the topic: rulers and scholars all wanted to now how practitioners could be so accurate underground…

It was performed by craftsmen trained hands-on in the mines. They had their own instruments, their own manuscripts, even their own language – the Bergmannsprache! Using lots of archive, I reconstruct how they worked and why geometry was so important, in the mines and beyond...

The development of #UndergroundMathematics mirrors larger developments: in every arts and crafts, quantification and accuracy were silently gaining ground. Early modern mathematics isn’t just about the ‘scientific revolution’, it’s a way broader cultural development!

My book presents case studies about maps, manuscript and prints, religion and politics set in the mines, in schools and at courts. The example of subterranean geometry shows the complex relationships between craftsmen and scientists, and the huge impact of practical mathematics!

‘A sophisticated, authoritative and original analysis’ (Jim Bennet), a ‘thoroughly researched book [that] presents fascinating stories’ (Ursula Klein, @MPIWG), it ‘offers a rare glimpse on how a specific mathematical culture developed’ (Jeanne Peiffer,@CAK_UMR)! #HistSTM

Thanks to all the people who helped me during the nine (yes, 9) years it took to complete this project ❤️. I sincerely hope you’ll find this a stimulating reading!

Preorders at @CambridgeUP and all kind of information cambridge.org/9781009267304!

Preorders at @CambridgeUP and all kind of information cambridge.org/9781009267304!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh