This self-portrait, from 1556, is by Sofonisba Anguissola.

She was regarded by everyone from the Pope to Michelangelo as the greatest female artist of the Renaissance.

Here is the story of her long and fascinating life...

She was regarded by everyone from the Pope to Michelangelo as the greatest female artist of the Renaissance.

Here is the story of her long and fascinating life...

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was born to an aristocratic family in Cremona, a city in northern Italy.

Her unusual name stems from a family tradition of using Carthaginian names; Cremona was near the site of Hannibal's victory over Rome at the Battle of the Trebia in 218 BC.

Her unusual name stems from a family tradition of using Carthaginian names; Cremona was near the site of Hannibal's victory over Rome at the Battle of the Trebia in 218 BC.

Her father, Amilcare, was a learned man. He ensured that his six daughters received a proper education and encouraged them to pursue the fine arts.

Sofonisba's talent was soon revealed - it would one day take her all around Europe, both in person and in her fame.

Sofonisba's talent was soon revealed - it would one day take her all around Europe, both in person and in her fame.

She started painting at the age of 14 and studied under prominent Cremona-based painters like Bernardino Gatti and Giulio Campo.

They were a big influence on Anguissola with their sumptuous colours, textures, and rather freely drawn, almost loose brushwork.

They were a big influence on Anguissola with their sumptuous colours, textures, and rather freely drawn, almost loose brushwork.

But her main tutor was Bernardino Campo. Here he is in one of the Renaissance's most interesting portraits.

Anguissola depicted Campo, her tutor, painting a portrait of herself. It's funny and self-referential, but also speaks of a highly inventive and confident young artist.

Anguissola depicted Campo, her tutor, painting a portrait of herself. It's funny and self-referential, but also speaks of a highly inventive and confident young artist.

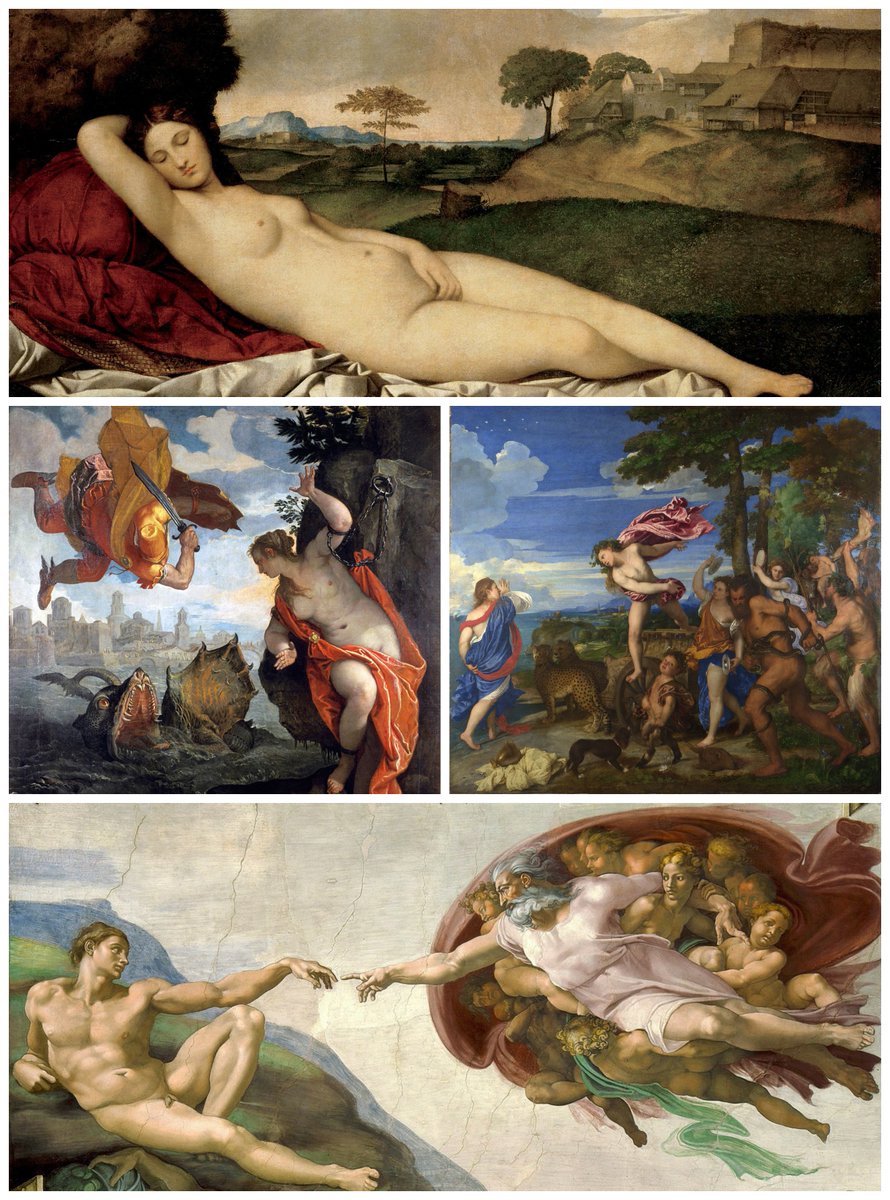

When we think of Renaissance art we imagine Classical, Biblical, and historical scenes featuring idealised human forms; that's not the sort of thing Anguissola painted.

Partially because it was improper for women to study the anatomy of nudes; a whole genre she couldn't access.

Partially because it was improper for women to study the anatomy of nudes; a whole genre she couldn't access.

And so Anguissola was limited almost exclusively to portraits.

But it seems that her focus on them brought out an unusual intimacy, warmth, and familiarity which is often lacking in the graceful but distant art of the Renaissance.

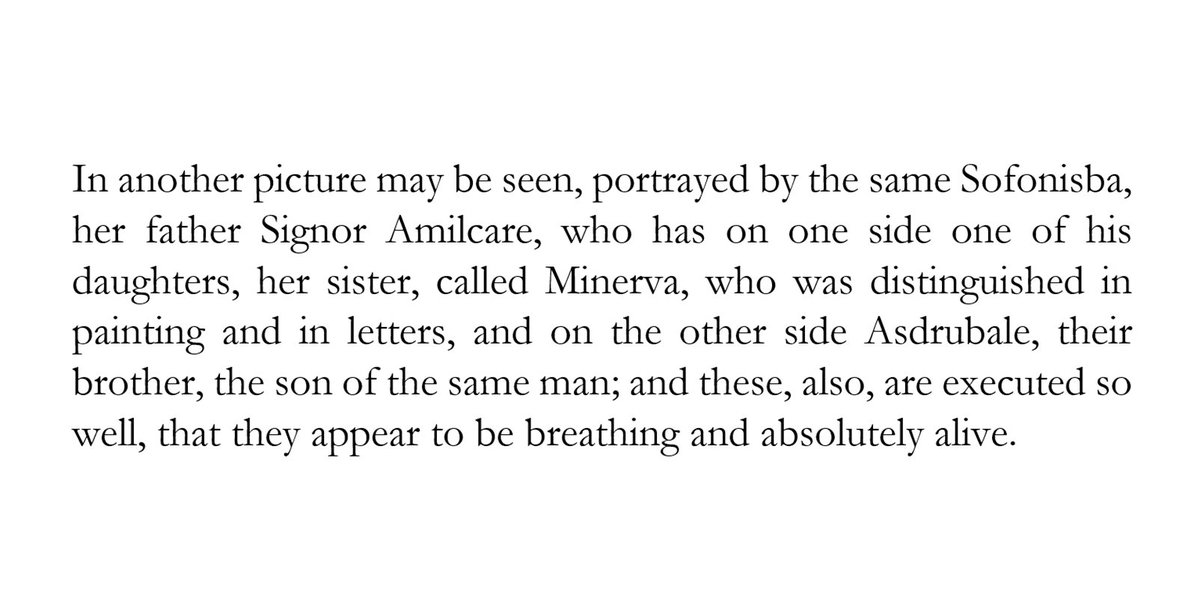

Here we see her father and two siblings:

But it seems that her focus on them brought out an unusual intimacy, warmth, and familiarity which is often lacking in the graceful but distant art of the Renaissance.

Here we see her father and two siblings:

In 1554, aged 22, Anguissola travelled to Rome.

There she was introduced to Michelangelo, who was *the* most famous artist on the continent - a living legend.

She showed him a sketch of a laughing boy. He was not impressed and asked her to draw something more difficult...

There she was introduced to Michelangelo, who was *the* most famous artist on the continent - a living legend.

She showed him a sketch of a laughing boy. He was not impressed and asked her to draw something more difficult...

He wanted to see pain; an expression far harder to depict.

So Anguissola drew this - Boy Bitten by a Crayfish.

Thoroughly impressed, Michelangelo recognised her immense talent and shared his sketches with her; for two years he provided a mixture of advice and informal tutoring.

So Anguissola drew this - Boy Bitten by a Crayfish.

Thoroughly impressed, Michelangelo recognised her immense talent and shared his sketches with her; for two years he provided a mixture of advice and informal tutoring.

Giorgio Vasari, who lived in the 16th century and wrote miniature biographies of the greatest artists of the age, from Leonardo to Raphael and all the rest, also wrote about Anguissola.

Here is what he wrote about her, impressed above all by the liveliness of her work:

Here is what he wrote about her, impressed above all by the liveliness of her work:

Perhaps her greatest painting - another admired by Vasari - is this, of her sisters playing chess.

There's a striking naturalism and candidity about this painting, along with her typical warmth and affection, not to mention the exquisite colours and textures.

There's a striking naturalism and candidity about this painting, along with her typical warmth and affection, not to mention the exquisite colours and textures.

She also painted self-portraits throughout her life.

In Self-Portrait with an Easel and Self-Portrait at a Spinet (a type of musical instrument), both from the 1550s, we see Anguissola portraying herself in the act of creation.

A clear statement about how she viewed herself.

In Self-Portrait with an Easel and Self-Portrait at a Spinet (a type of musical instrument), both from the 1550s, we see Anguissola portraying herself in the act of creation.

A clear statement about how she viewed herself.

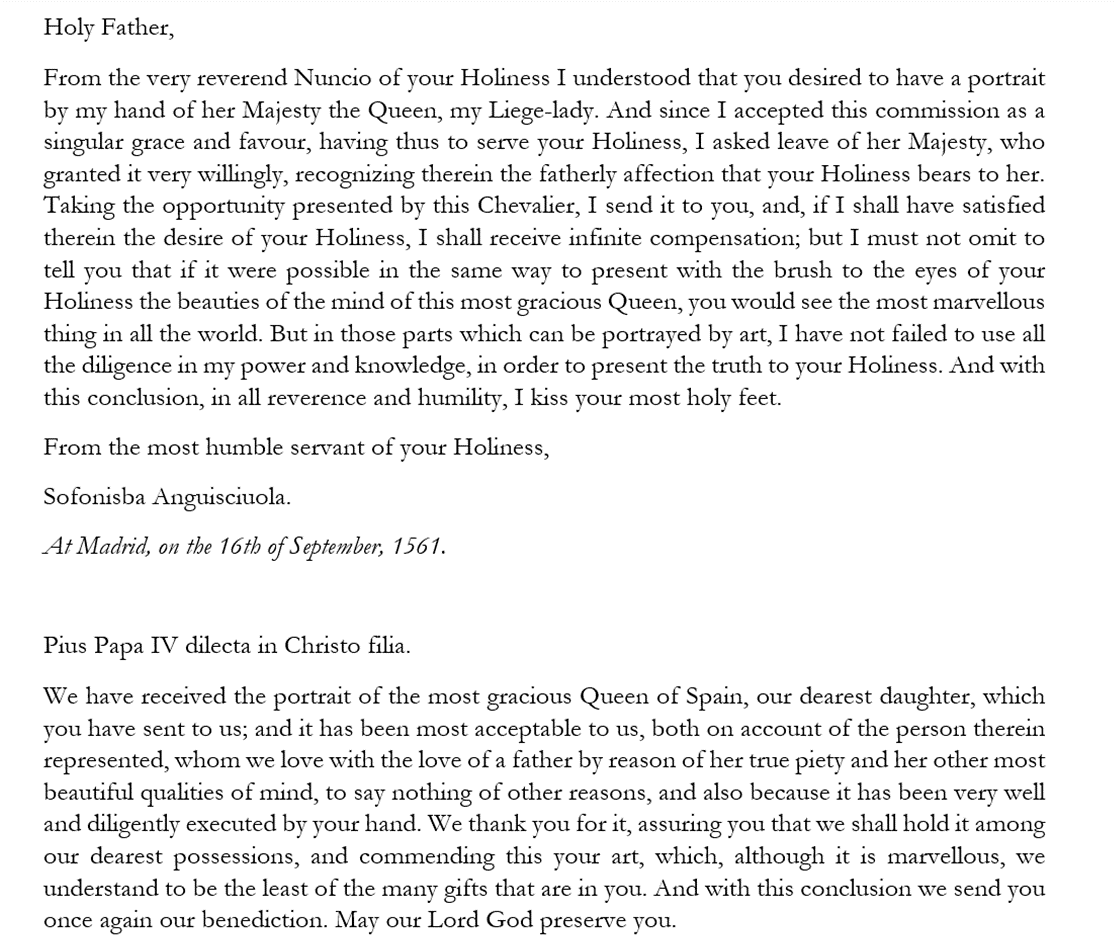

Anguissola's fame had started to grow, even beyond Italy. In 1558 she went to Milan and made a portrait for the Duke of Alba, who then recommended her to the king of Spain, Philip II.

In 1560 she travelled there, becoming a tutor to his wife and an official court painter:

In 1560 she travelled there, becoming a tutor to his wife and an official court painter:

She stayed in Spain for fourteen years, and in that time created a host of official portraits for the Spanish court.

This required a change in style. Her old intimacy was replaced by regality, her warmth by royal dignity.

This required a change in style. Her old intimacy was replaced by regality, her warmth by royal dignity.

Yet her portraits lost none of their liveliness.

From Anguissola's depiction of Elisabeth of Valois, Queen of Spain, we can discover something of the Queen's personality.

Thirty years later, she would paint the Queen's daughter in the same pose.

From Anguissola's depiction of Elisabeth of Valois, Queen of Spain, we can discover something of the Queen's personality.

Thirty years later, she would paint the Queen's daughter in the same pose.

During her long life Anguissola made portraits for all sorts of people. From poets and painters to the Holy Roman Emperor and Francesco Medici, there was no shortage of dukes, princes, nobles, and artists whose likenesses she was hired to capture.

Pope Pius IV had heard about Anguissola, too. He wrote to her, asking for a portait of the Queen of Spain. Anguissola duly obliged. Their correspondence survives.

In Vasari's words, "let this testimony suffice to prove how great is the talent of Sofonisba."

In Vasari's words, "let this testimony suffice to prove how great is the talent of Sofonisba."

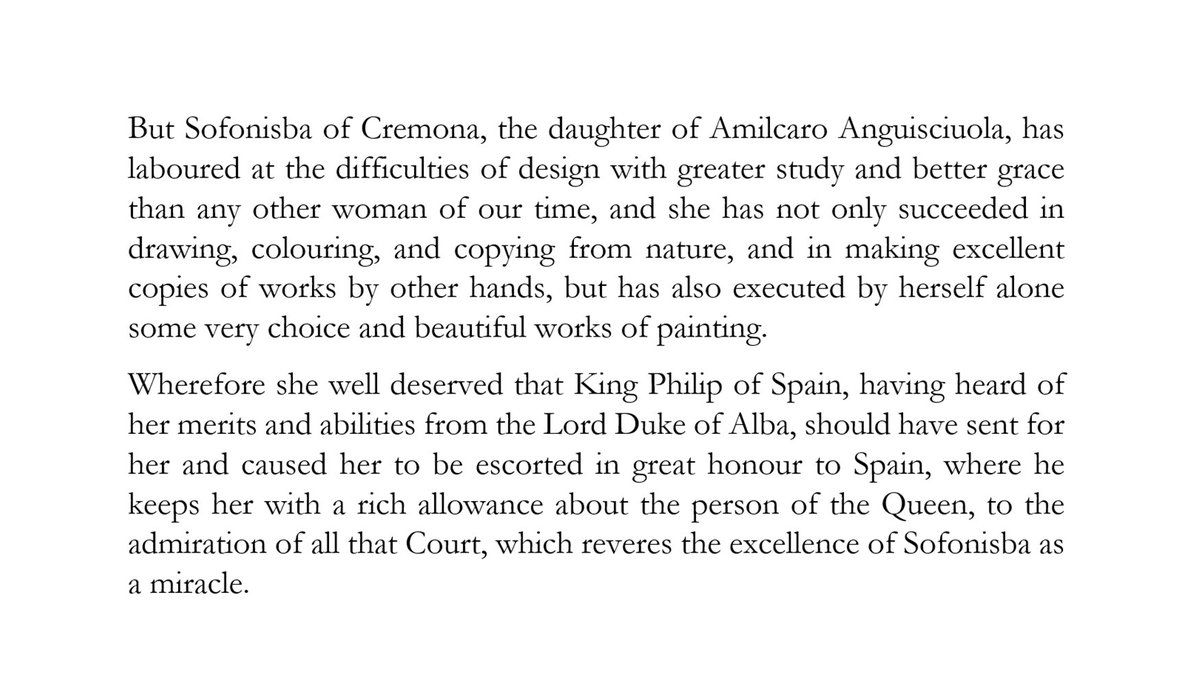

Vasari, at a time when Anguissola was working in Spain and thus lamenting the lack of availability of her work in Italy, wrote this about her.

For Vasari, she was the foremost female painter of the age.

For Vasari, she was the foremost female painter of the age.

By 1571 Elisabeth had died and Anguissola wanted to leave the Spanish court.

King Philip agreed; he paid the dowry for her marriage to the son of the Viceroy of Sicily and set her up with a pension that allowed her to live comfortably for the rest of her life.

King Philip agreed; he paid the dowry for her marriage to the son of the Viceroy of Sicily and set her up with a pension that allowed her to live comfortably for the rest of her life.

They moved to Sicily but he died in 1579. So Anguissola returned to Cremona. She fell in love with and married the captain of the ship that took her there, Orazio Lomellino.

Back in Italy Anguissola continued her portrait work and became a tutor to young painters.

Back in Italy Anguissola continued her portrait work and became a tutor to young painters.

And in her later career, as a widely known and respected artist with a healthy fortune, Anguissola turned to religious themes.

After many years of regal portraiture, that wonderful intimacy from her early years returned. Her style had matured too; darker, but no less warm.

After many years of regal portraiture, that wonderful intimacy from her early years returned. Her style had matured too; darker, but no less warm.

This was her final self-portait, painted in 1610.

From the prodigious talent who had impressed Michelangelo in her early twenties to a travelled and famous artist who had met and painted the great and good of the earth.

From the prodigious talent who had impressed Michelangelo in her early twenties to a travelled and famous artist who had met and painted the great and good of the earth.

One of the artists who sought to learn from Anguissola was Anthony van Dyck; he visited her in 1623, when he was only twenty five.

Just as Anguissola had learned from the masters in her youth, she helped van Dyck - who would go on to become the leading court painter in England.

Just as Anguissola had learned from the masters in her youth, she helped van Dyck - who would go on to become the leading court painter in England.

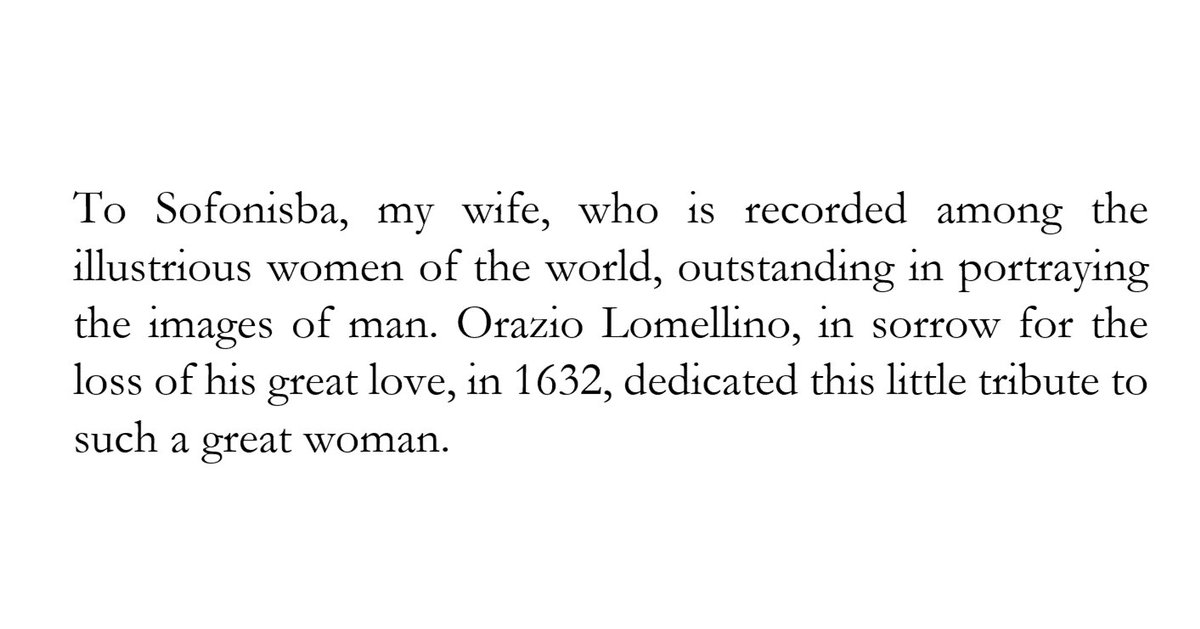

In 1624 she died - at the grand old age of 93. Anguissola's second husband, Orazio Lomellino, survived her.

This was what he wrote on her tombstone. A rather moving message.

This was what he wrote on her tombstone. A rather moving message.

And that's Sofonisba Anguissola, esteemed by Vasari and Michelangelo, portraitist of kings and emperors, and a painter whose life tells a different story of the Renaissance.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh