The hands of a clock move clockwise. To see a clock moving the other way feels incredibly wrong.

But there's no reason why it needs to be this way. Just like languages, which can be written left-right or right-left, an anticlockwise clock is perfectly understandable.

But there's no reason why it needs to be this way. Just like languages, which can be written left-right or right-left, an anticlockwise clock is perfectly understandable.

And seeing a clock with the numbers in the opposite order... that feels even stranger.

But, again, it makes just as much sense and is no less easy to read.

But, again, it makes just as much sense and is no less easy to read.

And so the answer lies in the origins of the clock.

What we know as clocks are mechanical (or digital) devices, but for most of history we didn't have them.

So, before the invention of the mechanical clock in the 14th century, how did people keep time?

What we know as clocks are mechanical (or digital) devices, but for most of history we didn't have them.

So, before the invention of the mechanical clock in the 14th century, how did people keep time?

There's been a few ways.

Such as the hourglass, which dates to the 8th century AD. It measures time with the falling of sand from one glass bulb to another.

Such as the hourglass, which dates to the 8th century AD. It measures time with the falling of sand from one glass bulb to another.

Then there are water clocks, which date to at least 1,400 BC, invented by different societies around the world. They didn't go out of use until 17th century because of their accuracy.

They keep time by slowly filling up a marked container with water, or by draining it.

They keep time by slowly filling up a marked container with water, or by draining it.

Candles have also been used for timekeeping.

They were marked at regular intervals with hours, so that the burning down of the wax indicated the passing of time.

They were marked at regular intervals with hours, so that the burning down of the wax indicated the passing of time.

But the oldest way of keeping time was with the sundial.

How does a sundial work? You basically put a stick in the ground and use its shadow to mark the passing of the hours.

How does a sundial work? You basically put a stick in the ground and use its shadow to mark the passing of the hours.

Well, it's a bit more complicated than that.

The sundial needs to be orientated and callibrated properly, depending on location, time of year, and orientation (vertically or horizontally), while the stick (known as a "gnomom") also needs to be shaped and placed in the right way.

The sundial needs to be orientated and callibrated properly, depending on location, time of year, and orientation (vertically or horizontally), while the stick (known as a "gnomom") also needs to be shaped and placed in the right way.

Anyway, as for clockwise and counterclockwise, they're relative terms: they both depend on your perspective

The earth's objective rotation is eastwards - that's true no matter which way you're looking at it.

The earth's objective rotation is eastwards - that's true no matter which way you're looking at it.

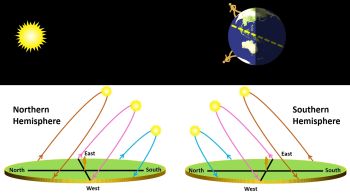

But if your perspective is the Northern Hemisphere, then the earth seems to be rotating anticlockwise.

Whereas if it's the Southern Hemisphere, the earth seems to be rotating clockwise.

Which means that, if you're facing the equator, the sun appears to move through the sky in different directions depending on where you are.

In the Northern Hemisphere it's left to right, and in the Southern Hemisphere it's right to left.

In the Northern Hemisphere it's left to right, and in the Southern Hemisphere it's right to left.

And so, given that the Northern Hemisphere rotates anticlockwise, the sun appears to move across the sky in the opposite direction, which is clockwise...

...along with its shadows.

Hence sundials in the Northern Hemisphere rotate, by nature, in a clockwise direction.

...along with its shadows.

Hence sundials in the Northern Hemisphere rotate, by nature, in a clockwise direction.

The mechanical clock was invented in Europe - in the Northern Hemisphere - and so its inventors naturally decided that its hands should rotate in the way people were used to.

Which, thanks of their sundials, meant clockwise.

Which, thanks of their sundials, meant clockwise.

And this also explains why the numbers are in the order they are.

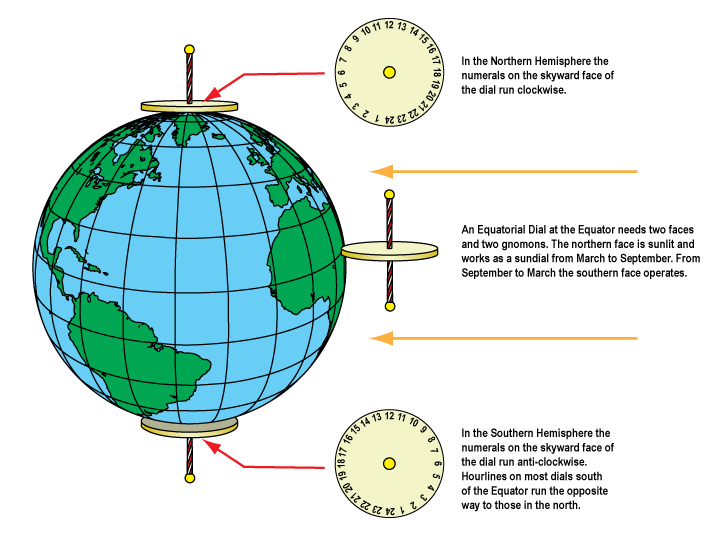

For sundials in the Northern Hemisphere to work properly they need to have midday pointing north, at the "top" of the sundial.

The clock's inventors simply used the same layout.

For sundials in the Northern Hemisphere to work properly they need to have midday pointing north, at the "top" of the sundial.

The clock's inventors simply used the same layout.

In the Southern Hemisphere it's the other way round.

A sundial has midday pointing south and moves anticlockwise.

So if the clock had been invented in the Southern Hemisphere then all of our watches and clocks would be rotating anticlockwise.

A sundial has midday pointing south and moves anticlockwise.

So if the clock had been invented in the Southern Hemisphere then all of our watches and clocks would be rotating anticlockwise.

Though, in that situation, clockwise and anticlockwise would be the other way round, too...

Anyway, none of this is to mention sundials on the equator - which look totally different!

Anyway, none of this is to mention sundials on the equator - which look totally different!

And that's why the hands of a clock rotate in the direction they do.

So, other than geography, it did have something to do with time - clocks were invented in the Northern Hemisphere first and the relevant sundial layout was adopted.

So, other than geography, it did have something to do with time - clocks were invented in the Northern Hemisphere first and the relevant sundial layout was adopted.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh