Classical Ash'arism, by which I mean here the school up to around the time of Razi, has a very strong appeal.

With only thin metaphysical assumptions, it can establish: the existence of God, the truth of Islam, the need for revealed morality; and (1/13)

With only thin metaphysical assumptions, it can establish: the existence of God, the truth of Islam, the need for revealed morality; and (1/13)

through occasionalism, it (arguably) can reconcile itself to any possible natural-scientific finding whatsoever. (2/13)

That is, classical Ash'arism can - without requiring many starting assumptions - give one rational justification for believing in Islam and following Islamic morality, whilst also leaving one free not to have to worry about the discoveries of natural science at all. (3/13)

The downside here is from the same source as the upsides: the thin assumptions.

To not make Islamic metaphysics dependent on an extensive premises, and to immunise these beliefs from conflicting with science, it makes limited positive claims about the nature of the world. (4/13)

To not make Islamic metaphysics dependent on an extensive premises, and to immunise these beliefs from conflicting with science, it makes limited positive claims about the nature of the world. (4/13)

'Limited' is a relative term: it is still telling us that God exists, some miracle reports are reliable, Islam is true, we can't reason our way to morality without the aid of revelation, and (5/13)

that there is no coherent distinction to be drawn between the natural order studied by science and God's activity.

But once we get there we can get no further, and we're also limited in our ability to defend the starting points which got us there in the first place. (6/13)

But once we get there we can get no further, and we're also limited in our ability to defend the starting points which got us there in the first place. (6/13)

We seemed to be foreclosed from the possibility of developing a true, progressive, science of metaphysics which gradually expands and refines the positive claims about the world; but in so doing (7/13)

multiplies what we are required to accept and, crucially, runs more and more into risk of clashing with other sciences.

The greater the number of positive claims made about the world by one science, the more likely it's going to be in tension with those made by another. (8/13)

The greater the number of positive claims made about the world by one science, the more likely it's going to be in tension with those made by another. (8/13)

Consider e.g. the Thomist analysis of evolution by natural selection by John Deely, or of quantum mechanics by (my acquaintance) Bill Simpson.

If Muslims want an equivalent to the various Catholic progressive, scientific metaphysical research projects out there (9/13)

If Muslims want an equivalent to the various Catholic progressive, scientific metaphysical research projects out there (9/13)

- which we had once upon a time before the decline of aqliyyat in the last few centuries - we will not just be able to accept whatever natural science happens to say, nor rest on thin metaphysical assumptions without grounding them in a much more expansive system. (10/13)

Philosophical problems no longer become interminable disputes for humans to incessantly go back and forth about, but every one is answered and integrated into an ever advancing system (though there will always be the interminable debate over whether to accept that system).(11/13)

Do we want a metaphysics as a true science entitled to make, develop, and refine substantive claims about the world just as the other sciences do; or one which allows us to accept the other sciences whatever they say confident in our iman? (12/13)

There isn't an easy answer here, nor necessarily a right one: perhaps both are theologically legitimate.

Both can claim grounding in the tradition (ie pre- and post- Razi).

Allahu 'alam. (13/13)

Both can claim grounding in the tradition (ie pre- and post- Razi).

Allahu 'alam. (13/13)

Sum: "Solving" philosophical problems (eg of causality or knowledge) has costs, insofar as our answers require us to make substantive metaphysical claims about the world, and these might conflict with the claims or assumptions made by the natural sciences.

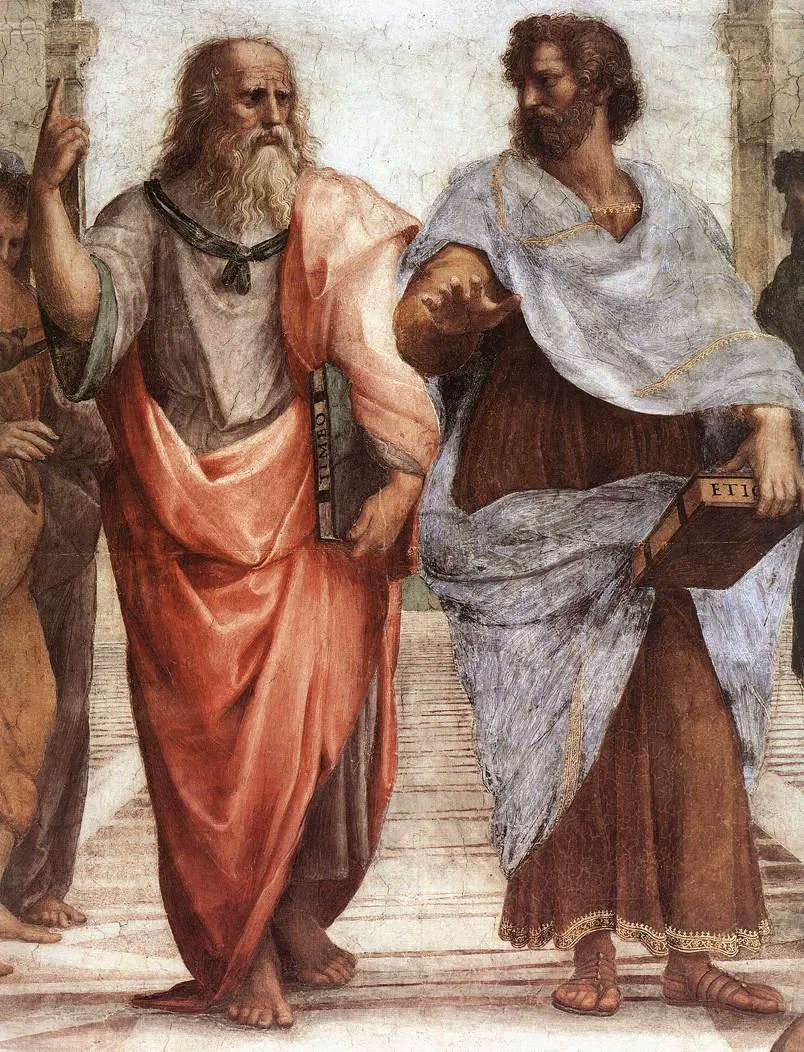

Illustration: the 20th century Thomist John Deely had a precise and incredibly elaborate system of metaphysics which purports to be able to solve every major issue in philosophy which has arisen over the ages, and which can justify his Catholicism, but the cost is that any (1/3)

natural-scientific finding becomes something which he may or may not be able to accept, and if he accepts which he may or may not have to revise his metaphysics for. (2/3)

We could have that; or we can have an unchanging system that can accept all findings, but doesn't tell us very much beyond the most core things, and struggles to justify those of its foundations which are contestable (although these are only few). (3/3)

The main virtue of classical Ash'arism summarised very well:

https://twitter.com/lastbondman/status/1606019955782098944?t=XP8fLncZ26-2Sc4DZ9ktEg&s=19

Addendum: Another aspect of the difference is that classical Ash'arism accommodates natural science more easily at the cost of making it harder to ascribe theological significance to it. (1/11)

As aforesaid, under occasionalism it is arguably the case that any possible finding of natural science can be accommodated.

However, given that the theory posits that there is nothing intrinsic to the natural world by which the natural order operates the way it does (2/11)

However, given that the theory posits that there is nothing intrinsic to the natural world by which the natural order operates the way it does (2/11)

rather than some other way or no way at all, what then is the significance of the way it does operate?

The classical Ash'aris themselves, being voluntarists, would say that there ultimately is none. But even without voluntarism - (3/11)

The classical Ash'aris themselves, being voluntarists, would say that there ultimately is none. But even without voluntarism - (3/11)

ie even assuming God's will and therefore the regularities in the natural world He causes is purposeful all the way down - it becomes hard to see what is being revealed to us human beings when we make a new natural scientific discovery. (4/11)

On certain strands of post-classical kalam, however, the situation is different.

Eg on Akbarianism, the natural order is intrinsically related to the natures of things in the created world themselves, which in turn (5/11)

Eg on Akbarianism, the natural order is intrinsically related to the natures of things in the created world themselves, which in turn (5/11)

(through the exemplar forms in the divine self-knowledge they participate in) manifest the divine Names and Attributes, and therefore instantiate in a limited way the infinite perfection and pure goodness of God Himself. (6/11)

Accordingly, the discoveries of natural science do not merely tell us about a contingent world that will soon be extinguished, but they inform us about eternal metaphysical truths: (7/11)

Every scientific discovery teaches us more about the natures of things, and therefore (if we have the eyes to see it) the Names and Attributes and perfection and goodness of God. (8/11)

The problem is, however, that not all scientific theories are compatible with this metaphysical system.

So when a theory is suggested, we have to ask: (1) whether we can accept it on our metaphysics; and (2) whether our metaphysics needs to be revised to accommodate it. (9/11)

So when a theory is suggested, we have to ask: (1) whether we can accept it on our metaphysics; and (2) whether our metaphysics needs to be revised to accommodate it. (9/11)

The other problem is that it's all well and good to say that under Akbarianism (or some other essence-realist strand of post-Razi kalam) natural science can reveal to us insights into God's Names and Attributes, it's harder to say what exactly those insights are. (10/11)

So perhaps there is ultimately no difference between the non-voluntarist occassionalist and essence-realism, save (the very big advantage) that the former can accommodate natural science more easily than the latter.

Allahu 'alam. (11/11)

Allahu 'alam. (11/11)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh