The original Santa Claus, so to speak, is Saint Nicholas (270-343 AD). He was an early Christian bishop born in Myra, modern-day Turkey, who became famous for working miracles and helping the needy.

In the 5th century the Roman Emperor Theodosius II built a church in his honour.

In the 5th century the Roman Emperor Theodosius II built a church in his honour.

One story tells how St Nicholas saved three young women from being forced into prostitution by dropping bags of gold through the windows of their house so that their father could afford a dowry to have them married:

And there's another story about a terrible famine, where a butcher captured and killed three young children, planning to sell them off as meat.

St Nicholas found the children, pickling in a barrel, and brought them back to life:

St Nicholas found the children, pickling in a barrel, and brought them back to life:

Every Christian saint has a feast day. In St Nicholas' case it was 6th December. Of course, the celebration of his day in the early Christian church was unlike what it is now.

But that's where the earliest traces of Santa Claus originate, in a gift-giving bishop from Turkey.

But that's where the earliest traces of Santa Claus originate, in a gift-giving bishop from Turkey.

It was the Christianisation of pagan Europe and the merging of religious cultures which helped create the figure we know today.

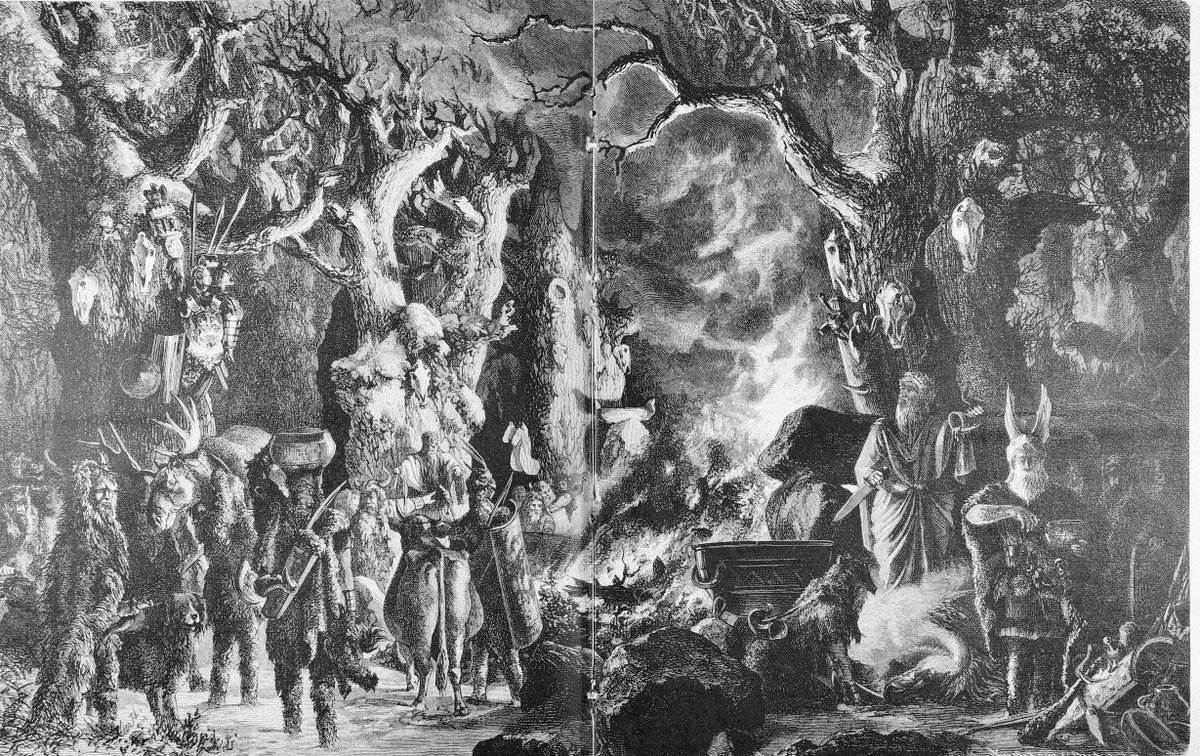

In Germanic paganism there was a midwinter festival called Yuletide which involved drinking, eating, and haunted nights.

In Germanic paganism there was a midwinter festival called Yuletide which involved drinking, eating, and haunted nights.

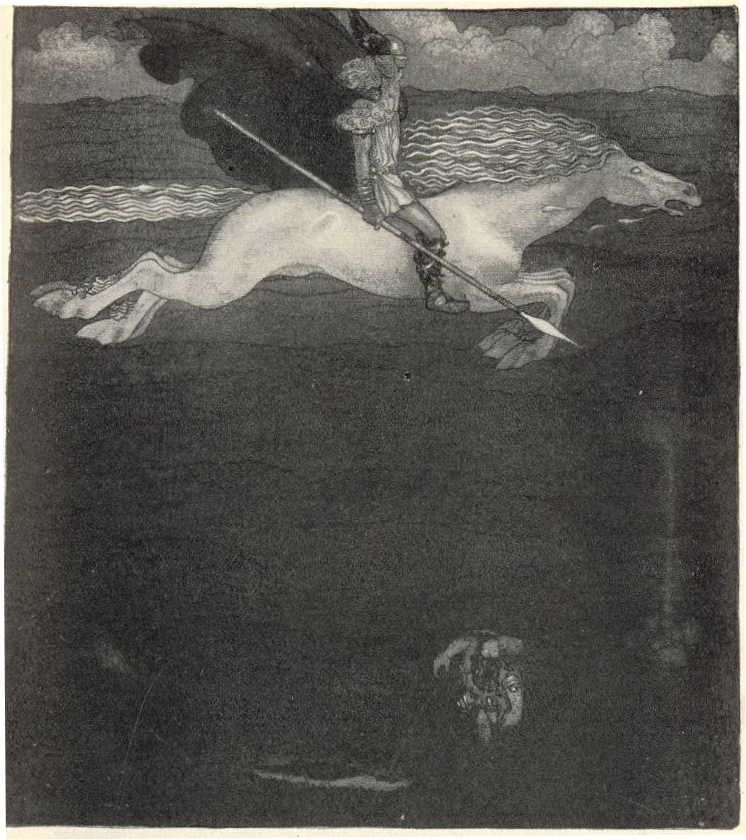

Yuletide was also associated with the Wild Hunt of Odin, a ride through the night-time sky of ghosts, valkyries, and other creatures led by Odin or some other mythological figure.

It may be in this that Santa Claus riding reindeer through the sky originates.

It may be in this that Santa Claus riding reindeer through the sky originates.

Another pagan figure who influenced Santa Claus was Krampus - who still exists as he once did in many countries - a scary creature who punished evil children on 5th December, before good children were rewarded with gifts on St Nicholas' feast the following day.

It was with these (and many other) pagan traditions that Saint Nicholas and his gift-giving feast day merged in a process whereby Christian rulers and preachers supplanted Yule as Christmastide - while keeping and adapting the old pagan traditions.

For example, the hearth (fireplace) played an important role in pagan worship, while in one version of the story about St Nicholas giving gold to the young women he did so through the chimney.

Which perhaps explains why Santa Claus comes down the chimney to deliver his gifts.

Which perhaps explains why Santa Claus comes down the chimney to deliver his gifts.

In the Netherlands Saint Nicholas became Sinterklaas, who wears a bishop's red robes and rides a white horse through the sky, just like Odin and his steed Sleipnir.

While St Nicholas' feast day on 6th December involved wild festivities and gift giving, especially to children.

While St Nicholas' feast day on 6th December involved wild festivities and gift giving, especially to children.

In many countries the 6th December - St Nicholas' original feast day - remains the time for gift giving.

So how did it move to the 25th December in other countries, the day of Jesus' birth and one essentially unrelated to St Nicholas?

So how did it move to the 25th December in other countries, the day of Jesus' birth and one essentially unrelated to St Nicholas?

The Reformation is why, as Protestantism rose and Catholic ways were cast off.

In the 1500s Martin Luther moved celebrations associated with the 6th December to 25th December. He disapproved of the Catholic veneration of saints and thought Christ's birth a more appropriate date.

In the 1500s Martin Luther moved celebrations associated with the 6th December to 25th December. He disapproved of the Catholic veneration of saints and thought Christ's birth a more appropriate date.

The same occurred in England, where Yule had also become Christmas and the celebrations associated with the Feast of St Nicholas moved to the 25th December.

While there it was the allegorical, paganistic figure of "Father Christmas" who had merged with Saint Nicholas.

While there it was the allegorical, paganistic figure of "Father Christmas" who had merged with Saint Nicholas.

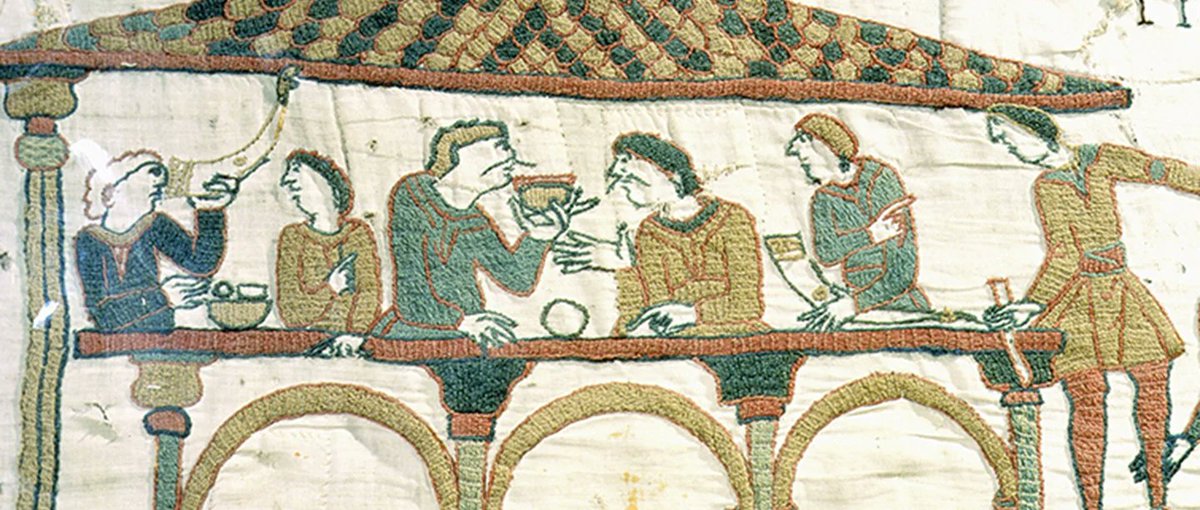

And so another key part of this story is the Medieval culture of feasting and merrymaking.

In the Middle Ages feast days - whether celebrating saints or anything else - were important occasions where special foods were eaten and people drank plentifully.

In the Middle Ages feast days - whether celebrating saints or anything else - were important occasions where special foods were eaten and people drank plentifully.

But down the centuries Christmas was a controversial celebration.

Its use of pagan traditions and extravagant, licentious celebrations involving mass drunkenness caused it to be banned in many countries at many different times.

Its use of pagan traditions and extravagant, licentious celebrations involving mass drunkenness caused it to be banned in many countries at many different times.

After the English Civil War in the 17th century the new Puritan regime under Oliver Cromwell banned Christmas for all those reasons.

After their fall Christmas was reinstated, and Father Christmas became even more closely associated with feasting and merrymaking.

After their fall Christmas was reinstated, and Father Christmas became even more closely associated with feasting and merrymaking.

This version of the figure is best-known from Charles Dicken's A Christmas Carol, during the Victorian revival of Christmas, as an old and jolly man with a big belly who symbolised merrymaking.

But it was from the USA that the modern Santa Claus would re-enter Europe.

But it was from the USA that the modern Santa Claus would re-enter Europe.

In 17th and 18th century America the Christmas figure of Dutch immigrants - Sinterklaas, anglicised as Santa Claus - and of English immigrants - merrymaking Father Christmas, celebrated on the 25th December - would merge to create the Santa Claus we know today.

The many different pagan and Christian traditions of Europe were consolidated in America into a single figure.

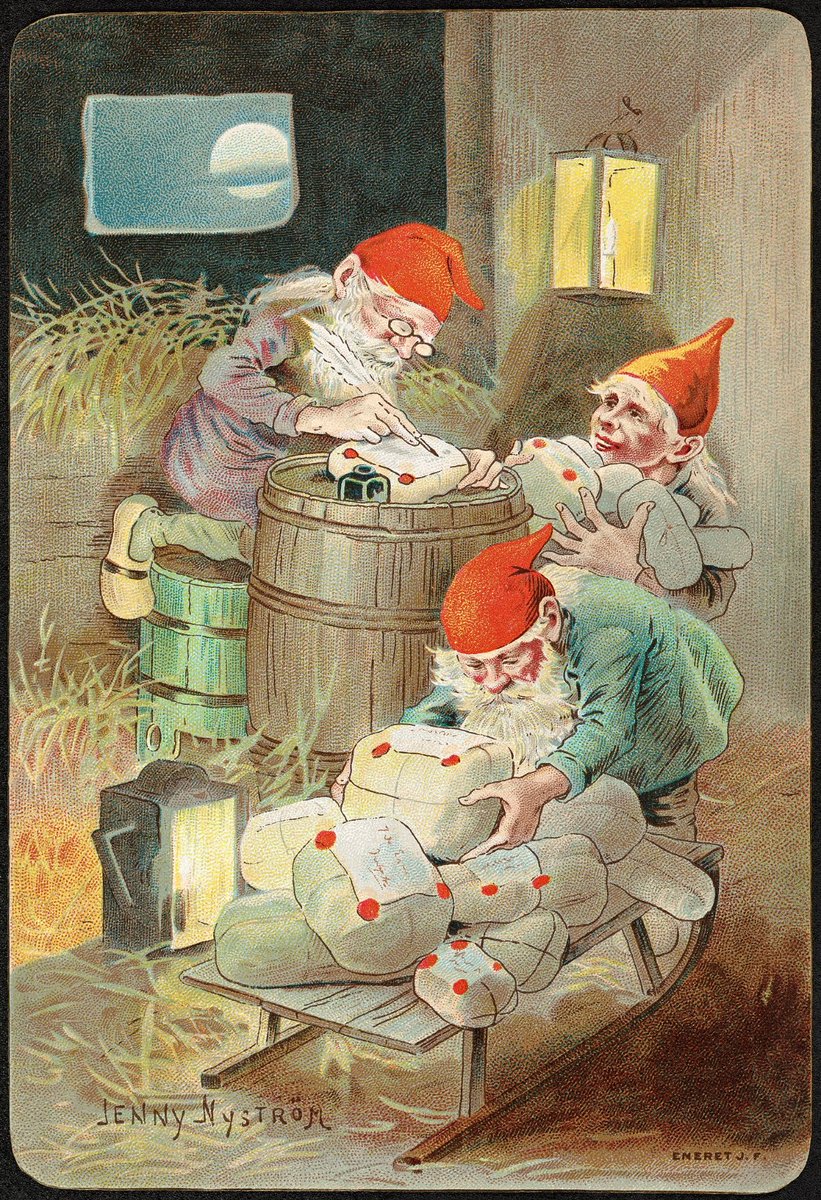

New things were formulated in the USA, too. Santa's helpers - the elves - seemingly came from the tomtenisse of Scandinavian folklore.

New things were formulated in the USA, too. Santa's helpers - the elves - seemingly came from the tomtenisse of Scandinavian folklore.

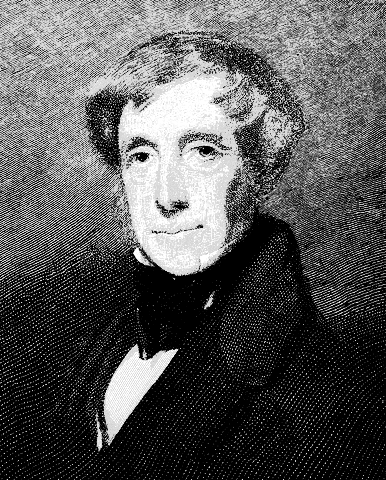

It was Clement Clarke Moore's 1823 poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas" which helped establish Santa Claus' image and many North American Christmas traditions.

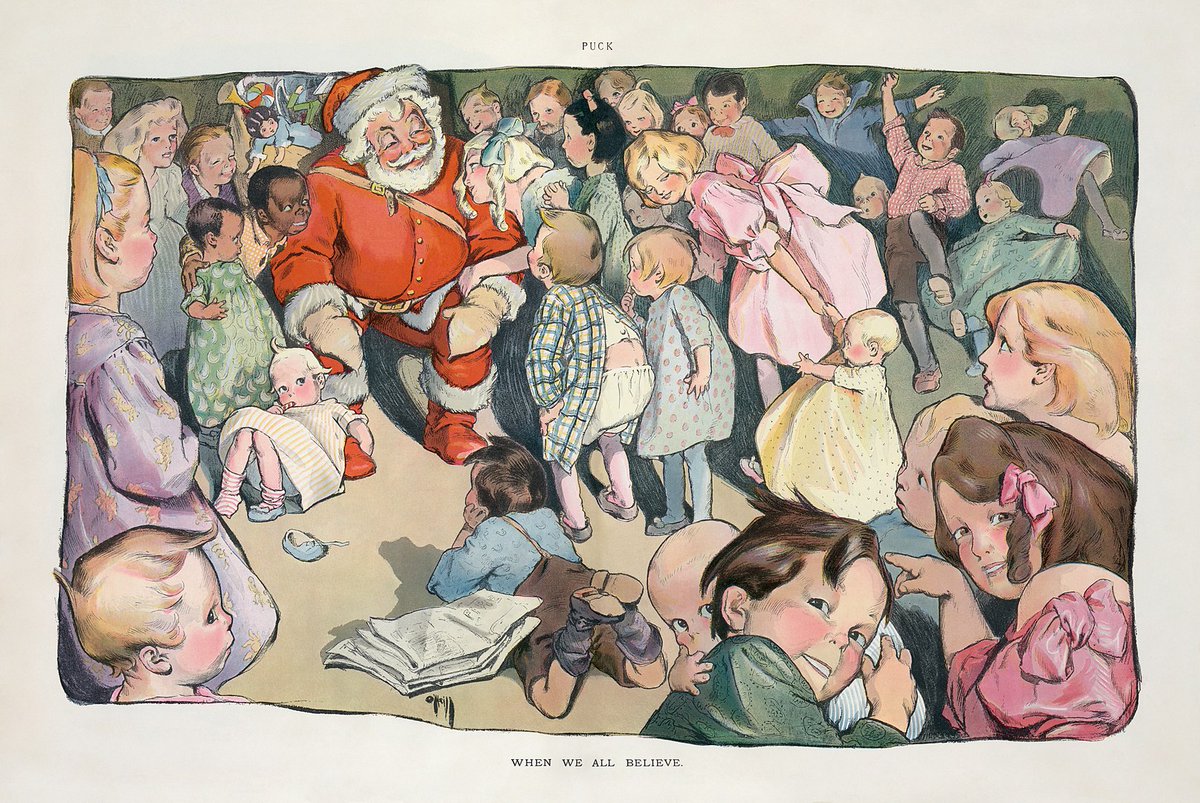

While the extravagant Medieval drinking was replaced with a more familial, child-focussed celebration.

While the extravagant Medieval drinking was replaced with a more familial, child-focussed celebration.

His apperance was further consolidated by the late 19th century cartoon illustrations of Thomas Nast.

Where Santa Claus had the red of St Nicholas' bishop's robes, the big belly of jolly Father Christmas, and the beard of so many pagan figures - a true cultural palimpsest.

Where Santa Claus had the red of St Nicholas' bishop's robes, the big belly of jolly Father Christmas, and the beard of so many pagan figures - a true cultural palimpsest.

Santa Claus, then, is a figure reconfigured over centuries from countless different traditions.

From the gift-giving of an ancient Christian bishop to the godly hunts of pagan mythology and Scandinavian elves to allegories for Medieval merrymaking, all distilled in the USA.

From the gift-giving of an ancient Christian bishop to the godly hunts of pagan mythology and Scandinavian elves to allegories for Medieval merrymaking, all distilled in the USA.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh