SARS-CoV-2 variant evolution: 2022 in review.

🧵

🧵

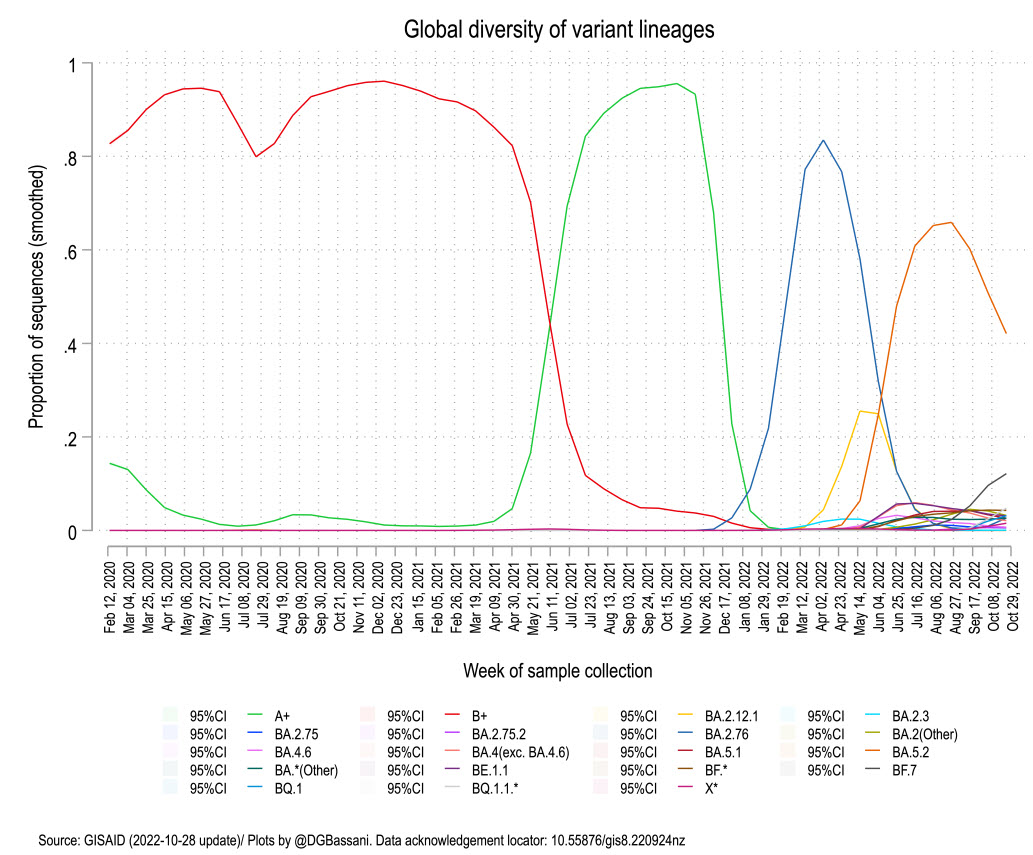

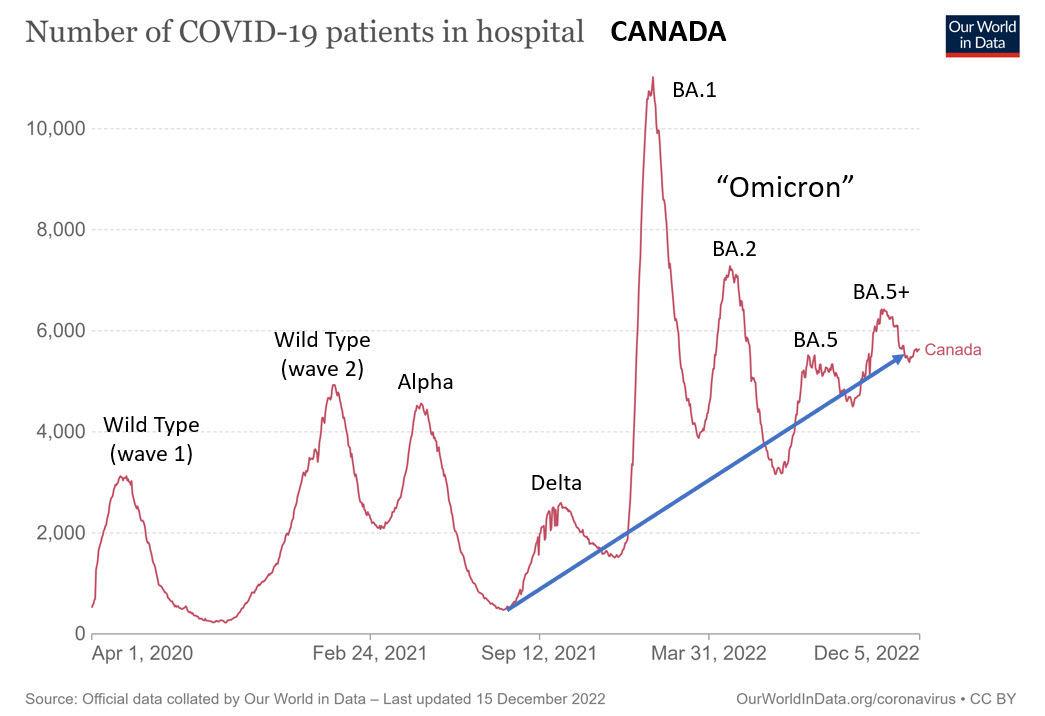

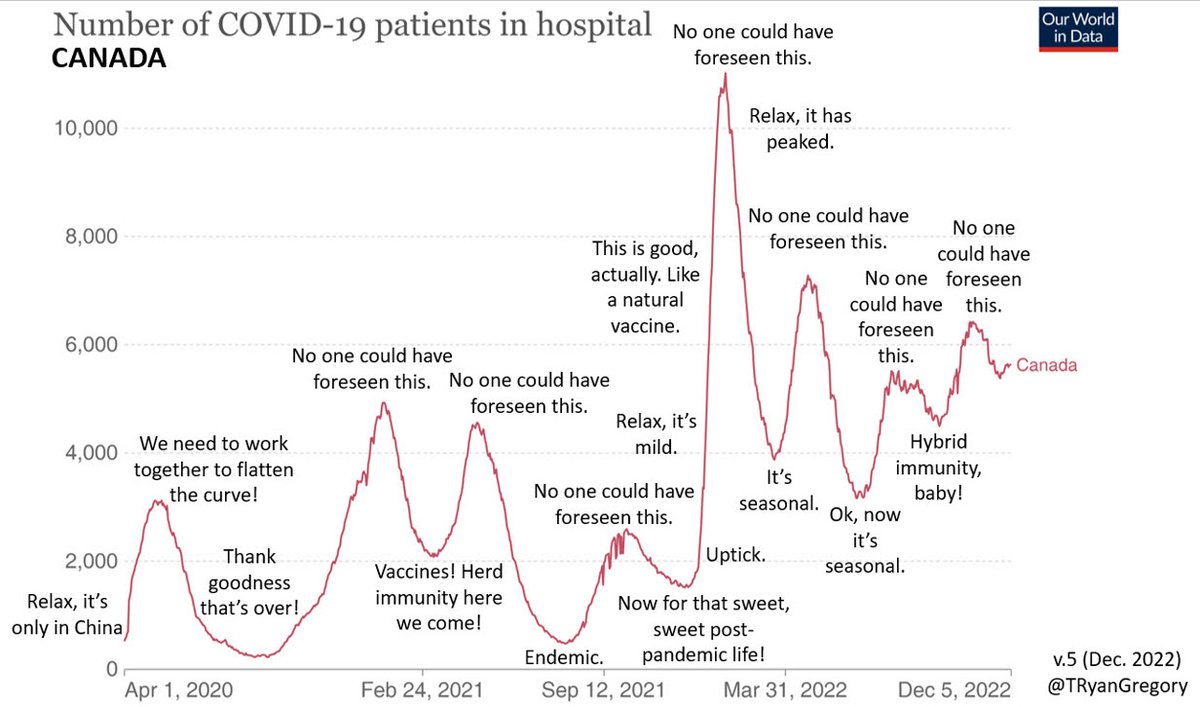

For background, recall that prior to summer 2022, we mostly had distinct waves each caused by a single variant. Depending on where you live, this may have included two wild type waves, then waves caused by Alpha, Delta, and the first Omicron.

https://twitter.com/TRyanGregory/status/1577617059525140480?s=20&t=pa9jdXqEN6zoRekletbWYg

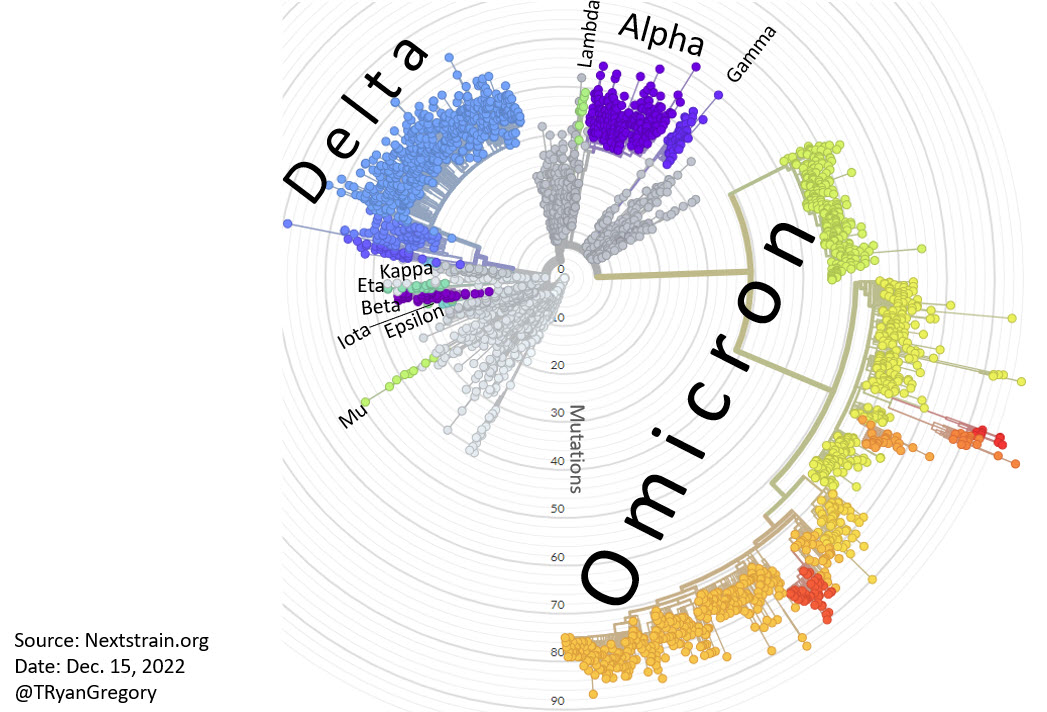

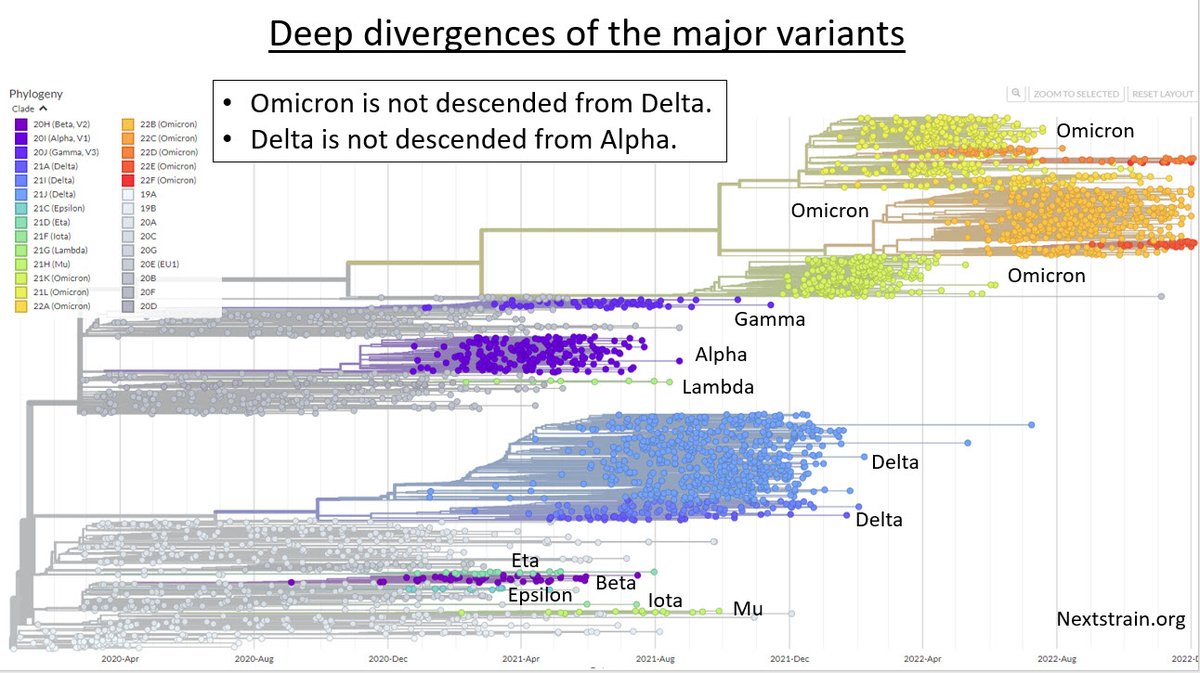

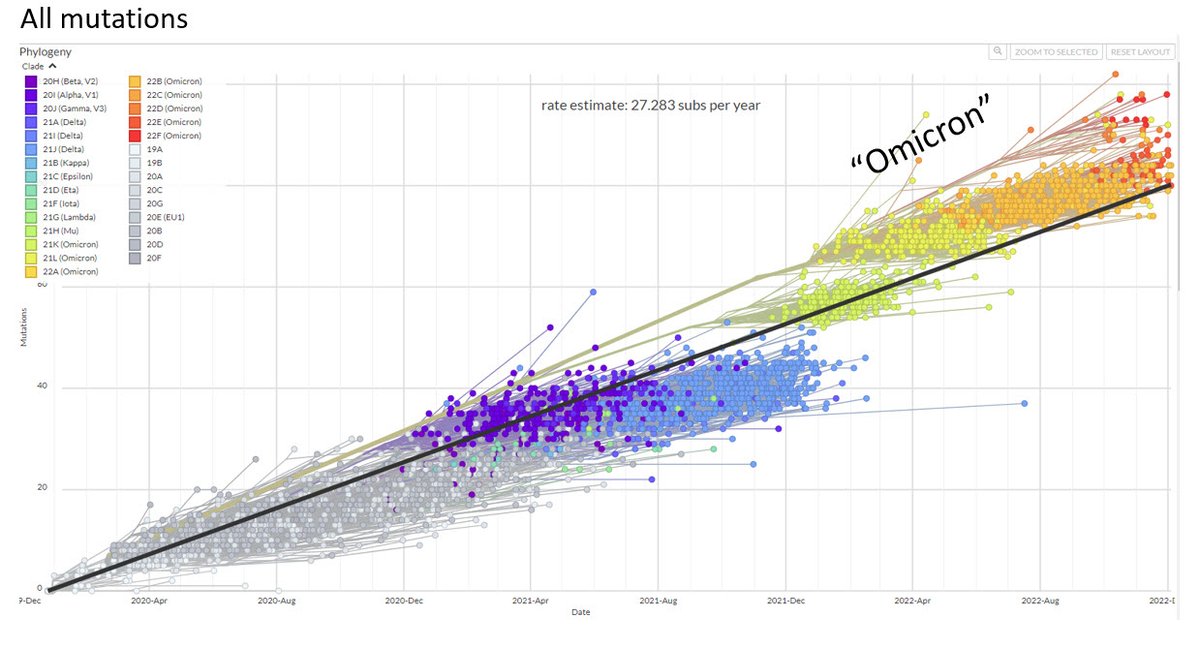

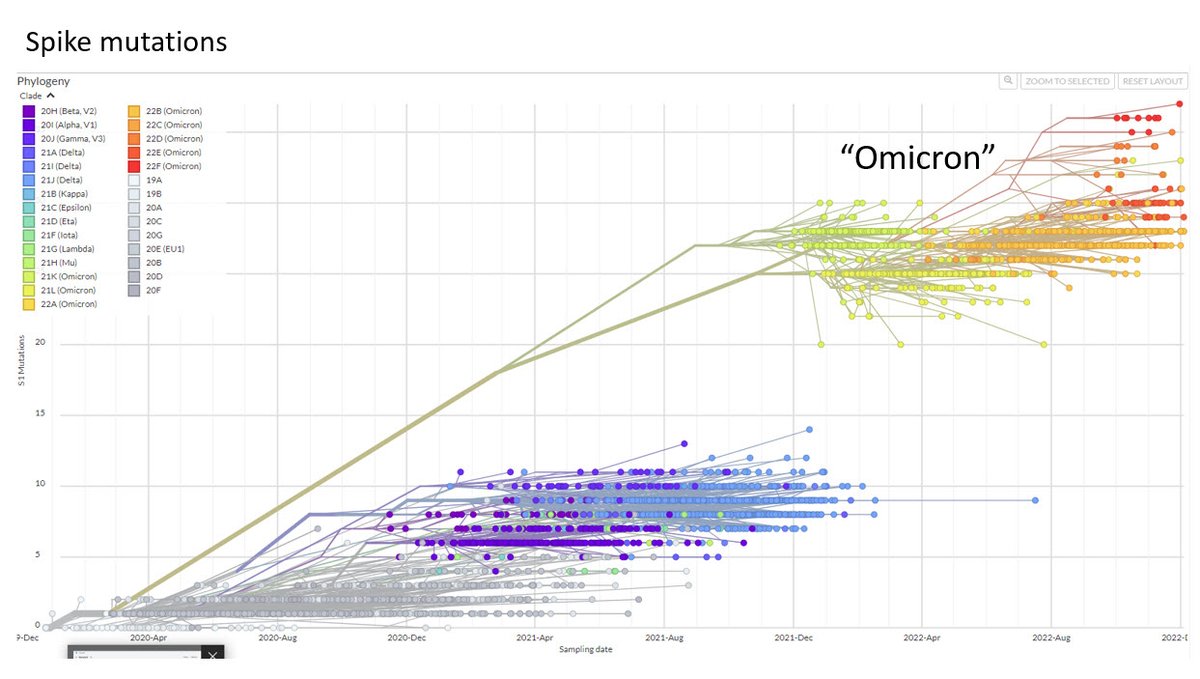

2022 has been the year of "Omicron", though in part that's simply because the @WHO refuses to assign any new Greek letter names. That it is all "Omicron subvariants" is more about semantics than biology. (Figures: nextstrain.org).

https://twitter.com/TRyanGregory/status/1576945959824523264?s=20&t=pa9jdXqEN6zoRekletbWYg

We did have distinct waves in many places caused by the first few Omicron variants (BA.1, BA.2, BA.5), but for the later part of 2022 we saw the evolution of a variant soup/cloud/swarm consisting of a number of immune-escaping variants co-existing. (Figure: @DGBassani).

Omicron evolution has been different in several important ways:

1) There has been a LOT of divergence. More than 650 subvariants have been identified within the Omicron lineage.

1) There has been a LOT of divergence. More than 650 subvariants have been identified within the Omicron lineage.

https://twitter.com/RajlabN/status/1607809761663406082?s=20&t=cWgJYHAEnq7Y30e_B7pQcg

2) There has been a lot of convergence as well. Most of the notable subvariants within Omicron exhibit similar suites of mutations, specifically ones that confer an advantage in terms of immune escape.

https://twitter.com/dfocosi/status/1609105670523047937?s=20&t=cWgJYHAEnq7Y30e_B7pQcg

3) We now have several highly immune-escaping variants circulating at the same time, each of them continuing to spawn new descendants. The most notable at the end of 2022 are the BQs and the XBBs.

The BQs are part of the BA.5 lineage. The XBBs are derived from a recombination event involving two BA.2 variants (BJ.1 x BM.1.1.1).

For more on how recombination occurs, see this excellent thread by @firefoxx66:

For more on how recombination occurs, see this excellent thread by @firefoxx66:

https://twitter.com/firefoxx66/status/1587762412110974976?s=20&t=cWgJYHAEnq7Y30e_B7pQcg

This year, some of us decided that we needed nicknames for variants worth watching, given that the @WHO wasn't giving any new names under their system. The first was BA.2.75, "Centaurus", named by @xabitron1.

We've been using mythological creature names for variants that are being discussed outside of technical discussions. The ones you're hearing about most now are:

BF.7 = Minotaur

BQ.1 = Typhon

BQ.1.1 = Cerberus

XBB = Gryphon

XBB.1 = Hippogryph

XBB.1.5 = Kraken

BF.7 = Minotaur

BQ.1 = Typhon

BQ.1.1 = Cerberus

XBB = Gryphon

XBB.1 = Hippogryph

XBB.1.5 = Kraken

4) There continues to be rapid evolution within Omicron. There is no shortage of new variation arising through mutation, and the more viruses there are replicating -- and making errors in the process -- the more variation there will be. (Figures: nextstrain.org).

5) New variants continue to evolve around the world. Right now there is a lot of emphasis on what may evolve in China, but it needs to be understood that anywhere with lots of virus can be the source of new variants, which then spread quickly around the globe.

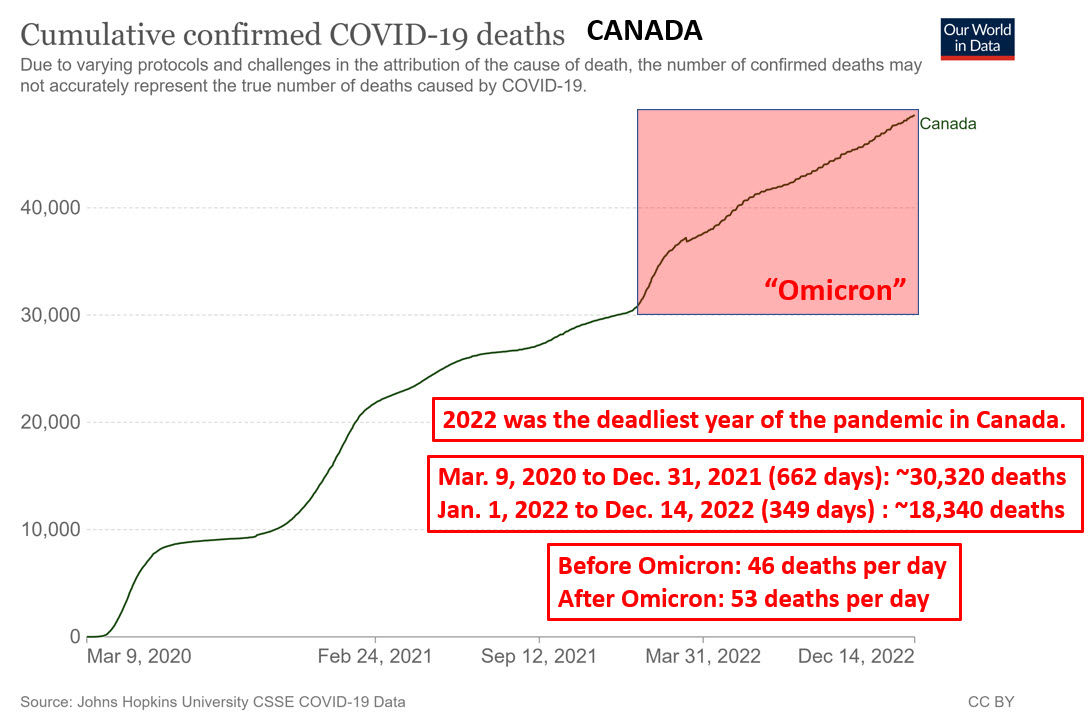

6) Omicron was not and is not mild. 2022 was the deadliest year of the pandemic in several countries, including Canada and the UK. Moreover, many countries have a much higher (and increasing) baseline for hospitalizations. It's not all about the height of each peak.

7) We may still see the evolution of a very different variant that would earn a name of "Pi" or "Rho" even under the much stingier naming conventions of the @WHO. There are at least four ways this could happen, all of them increased in likelihood by rampant transmission.

The (at least) four mechanisms are:

1) Within-host evolution (e.g., persistent infection in immunocompromised patient).

2) Recombination.

3) Ping pong zoonosis.

4) Evolution in a different direction within Omicron (under a different fitness landscape).

1) Within-host evolution (e.g., persistent infection in immunocompromised patient).

2) Recombination.

3) Ping pong zoonosis.

4) Evolution in a different direction within Omicron (under a different fitness landscape).

https://twitter.com/TRyanGregory/status/1596541873447145472?s=20&t=cWgJYHAEnq7Y30e_B7pQcg

In terms of China, I do think there will be significant new variant evolution which will be in a different direction (i.e., not just more convergence on immune escape mutations). It's a huge new population of previously unexposed hosts, and a very different fitness landscape.

All mechanisms of new variant evolution increase when you add 1.4 billion potential new hosts. It's entirely possible that more virulent variants will evolve (there will be that much more within-host evolution and so many accessible hosts means less selection against virulence).

However, a new variant from China may not compete well outside China where populations have different levels of immunity. That is, unless there is recombination with an immune-escaping variant that evolved outside China.

This is not intended to be doom and gloom. If we do nothing, then yes, much of what happens will be predictable (to some of us). However, we are certainly not powerless. We know how to mitigate transmission and reduce the impacts of variant evolution. Maybe in 2023?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh