The Intel 8086 processor was introduced in 1978, ancestor of the x86 architecture. The 8086 was the first microprocessor with prefetch, reading instructions from memory in advance for more speed. By reverse-engineering the chip under a microscope, I can explain how this works. 🧵

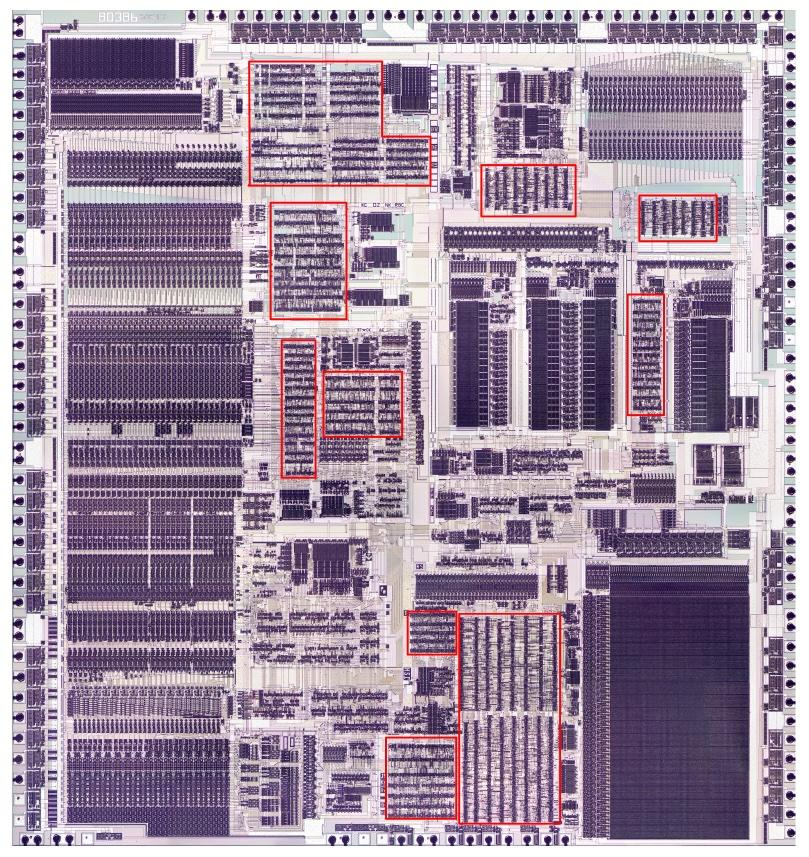

The 8086 has a 6-byte prefetch queue (photo), which is tiny compared to the megabytes of cache on modern processors, but it increased performance by about 50%. Intel ran a bunch of simulations to decide on the 6-byte queue (4-byte on the 8088 with its narrower 8-bit bus).

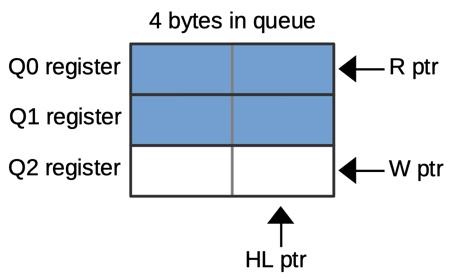

The prefetch queue was managed by a read pointer and a write pointer that kept track of the words in the queue. These 2-bit counters cycled 0-2. The HL flip flop indicated the high or low byte. The MT (empty) flip-flop indicated that the queue was empty.

This diagram zooms in on the prefetch pointers and associated logic on the die. This circuitry takes up a significant chunk of the die.

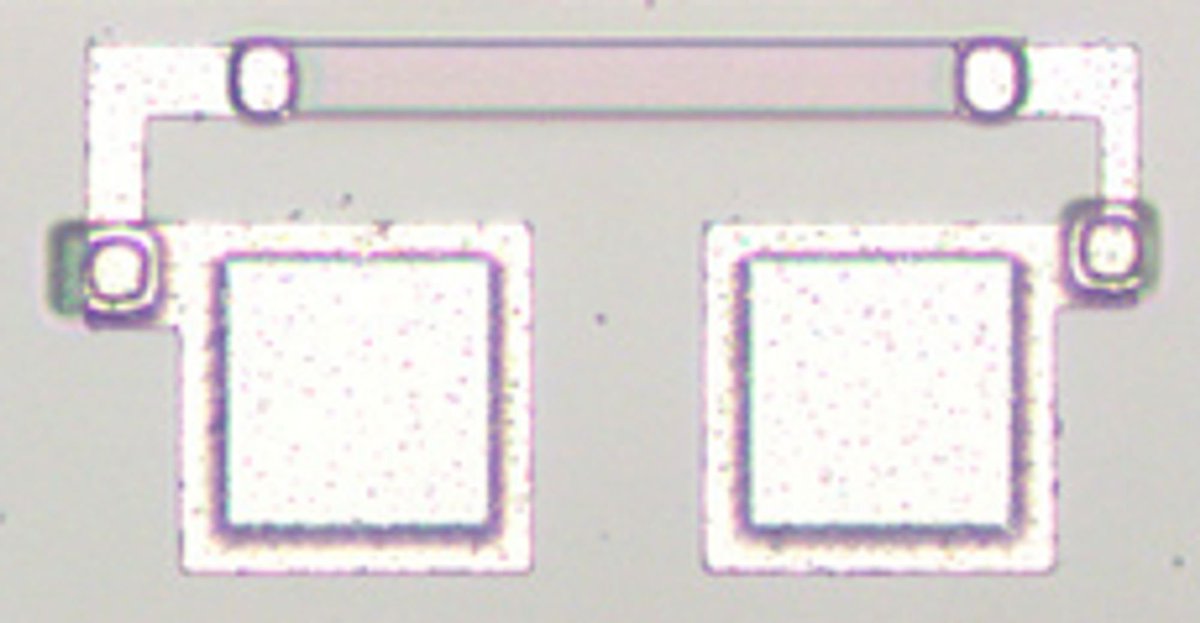

A processor's program counter or instruction pointer (IP) keeps track of what instruction it will execute. But prefetching moves the IP ahead of its "real" value. Subtracting the queue length gets the "real" IP. A Constant ROM holds constants -1 to -6 for this correction.

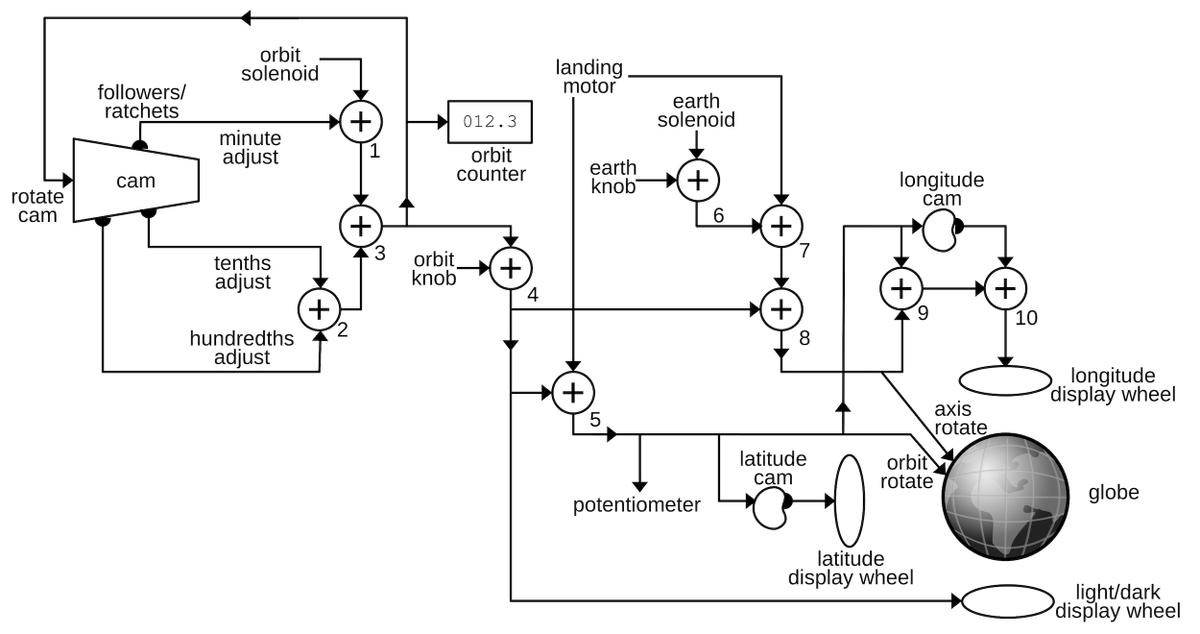

The interface between prefetching and the microcode engine was the "loader". This state machine fetched the first two bytes of the instruction from the queue. It also let microcode start the next instruction a cycle before the current one ended by pipelining decoding.

Prefetching added a lot of complications to the memory control circuitry since prefetches and "regular" memory accesses both needed to use the bus and needed to avoid conflict. My blog post has more information on how 8086 prefetching works: righto.com/2023/01/inside…

My previous 8086 thread:

https://twitter.com/kenshirriff/status/1599120928050483207

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh