Today in pulp I ask the question: is it time to bring back the custom street van?

Let's take a look...

Let's take a look...

For a short period - the late '60s to the early '80s - the coolest thing a hip young kid could drive was a tricked out van! That's why the Scooby-Doo gang had a custom Dodge A100, instead of a Ford Pinto.

...but the van is a very European thing, designed for twisty roads and narrow lanes. Compared to a US pick-up it looks like a bus. So how did it suddenly become street cool?

Well if you're going on surf safari you have a lot of gear to take with you: boards, beer, the guys, beer, a couple of guitars, beer, stuff for the cookout (like beer). I mean, you can try and sling it all into a Woody...

...or you could use a VW camper van! Known as the VW bus in the US (and the Kombi in Australia) this little van helped turn in America's youth to the idea of owning your own home from home - a van!

It turned out vans were kinda cool. You could road trip in them, go to festivals or hit the beach, and take everything you needed with you. And it was way cooler than a traditional RV because you could mod it!

Styling your van made your wheels into a personal statement: you weren't no square in a station wagon, you were a bell-bottomed, freedom-loving child of nature. You just wanted something you could sleep in as well.

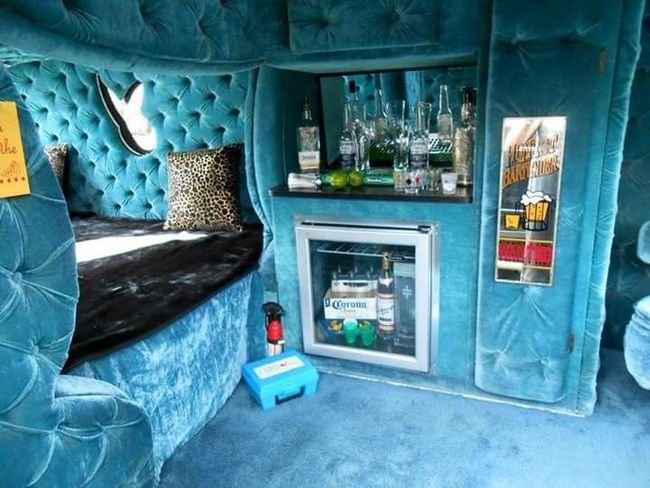

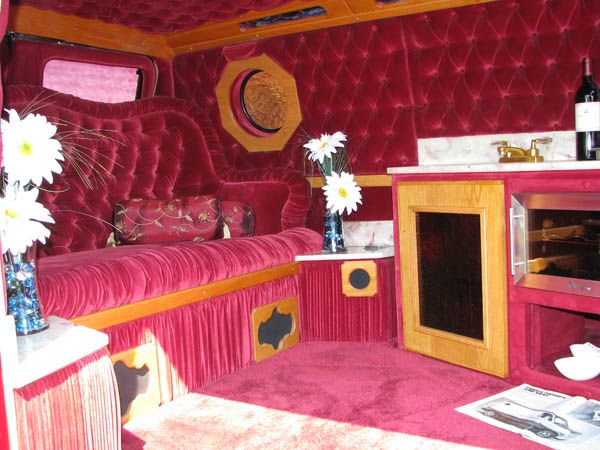

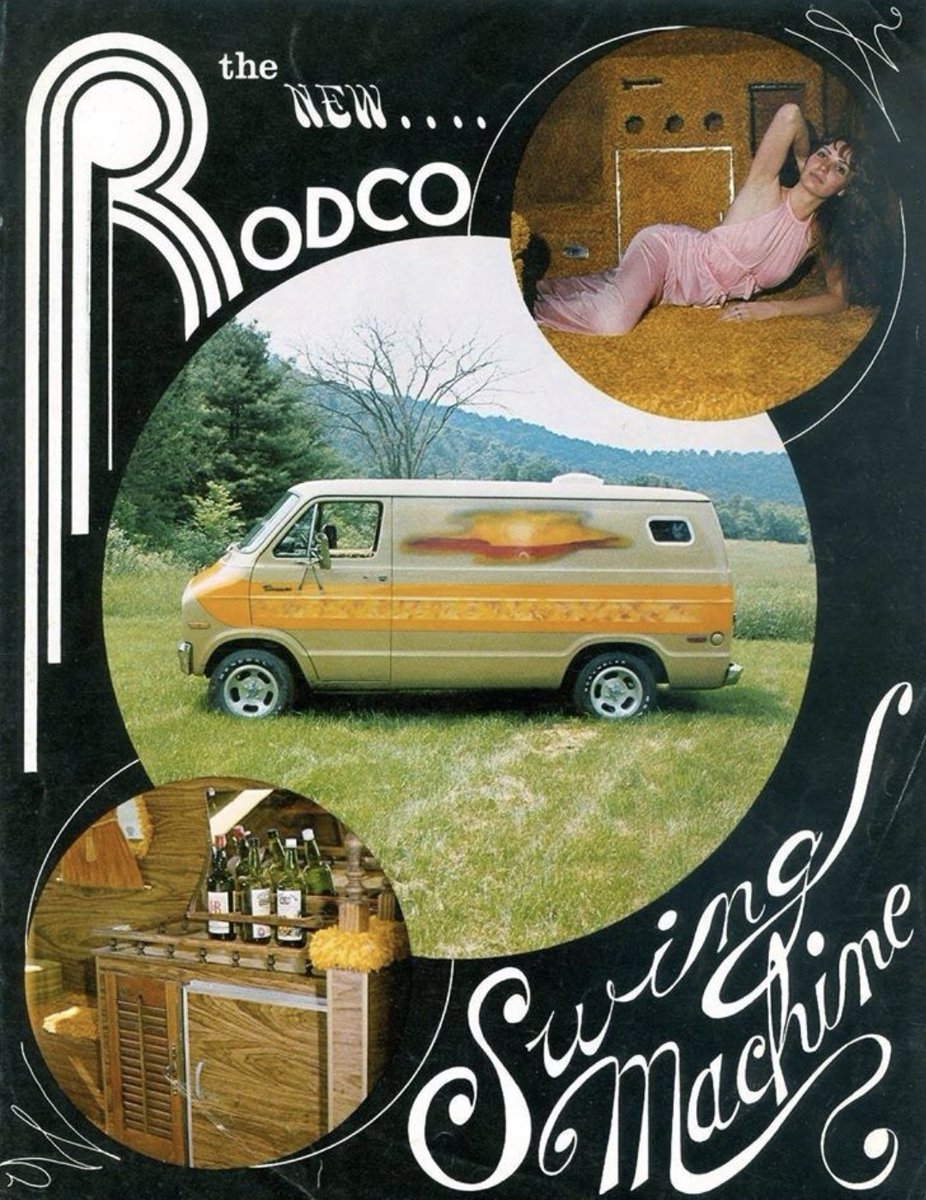

The inside of the van had to be as cool as the outside. Velour, shagpile, teak, quilting, leopard print: whatever it took to make a statement.

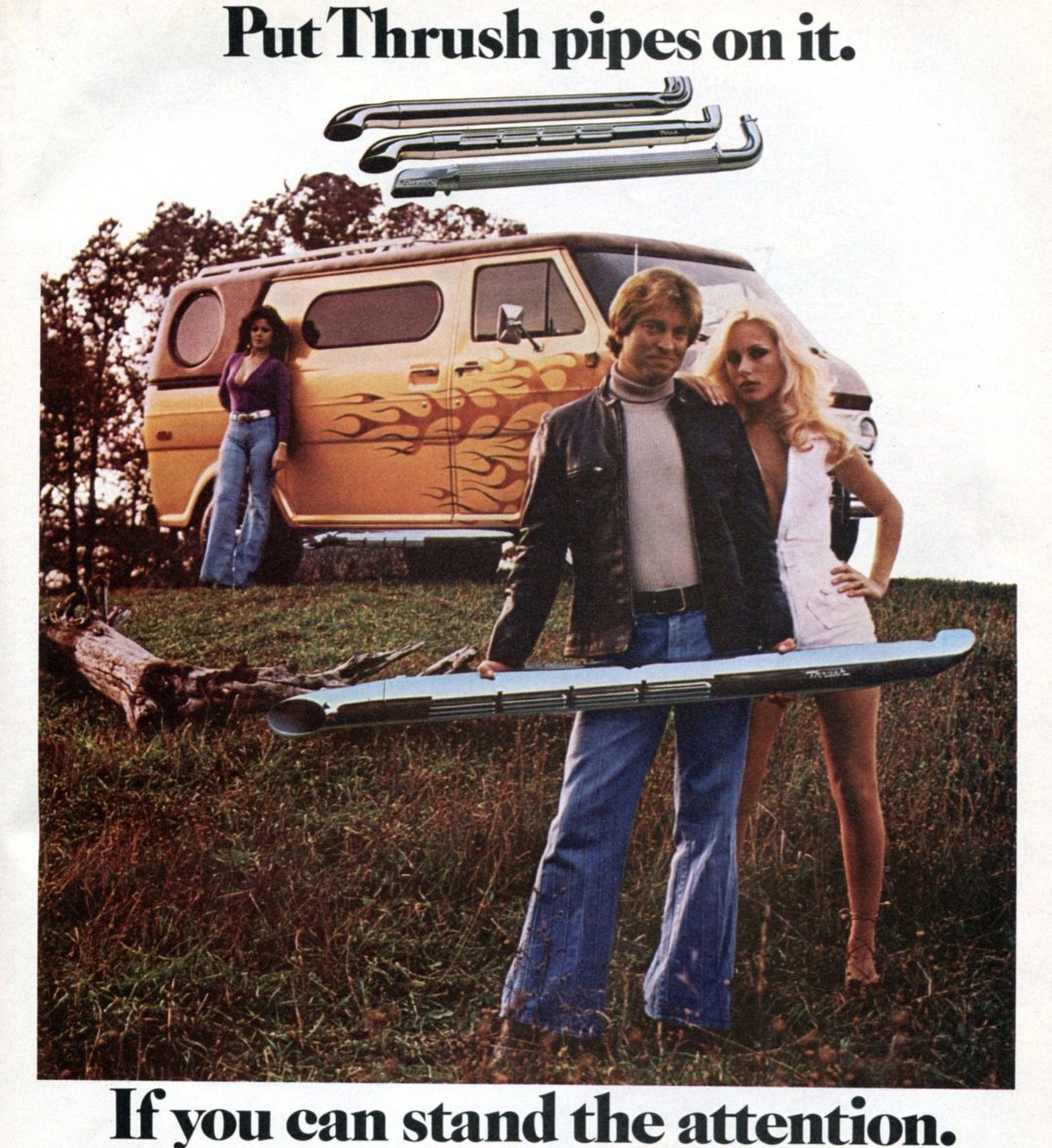

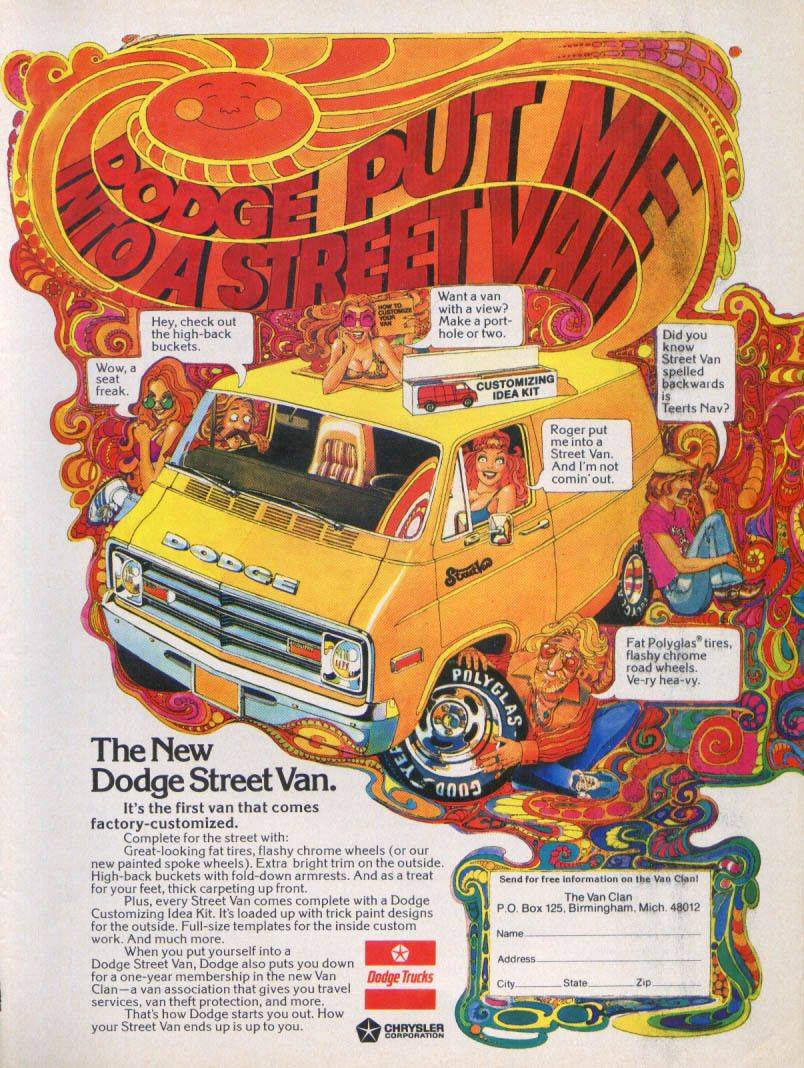

Pretty soon major manufacturers started to cash in on this new van craze, offering custom paintjobs and selling the allure of good times to the van-starved masses.

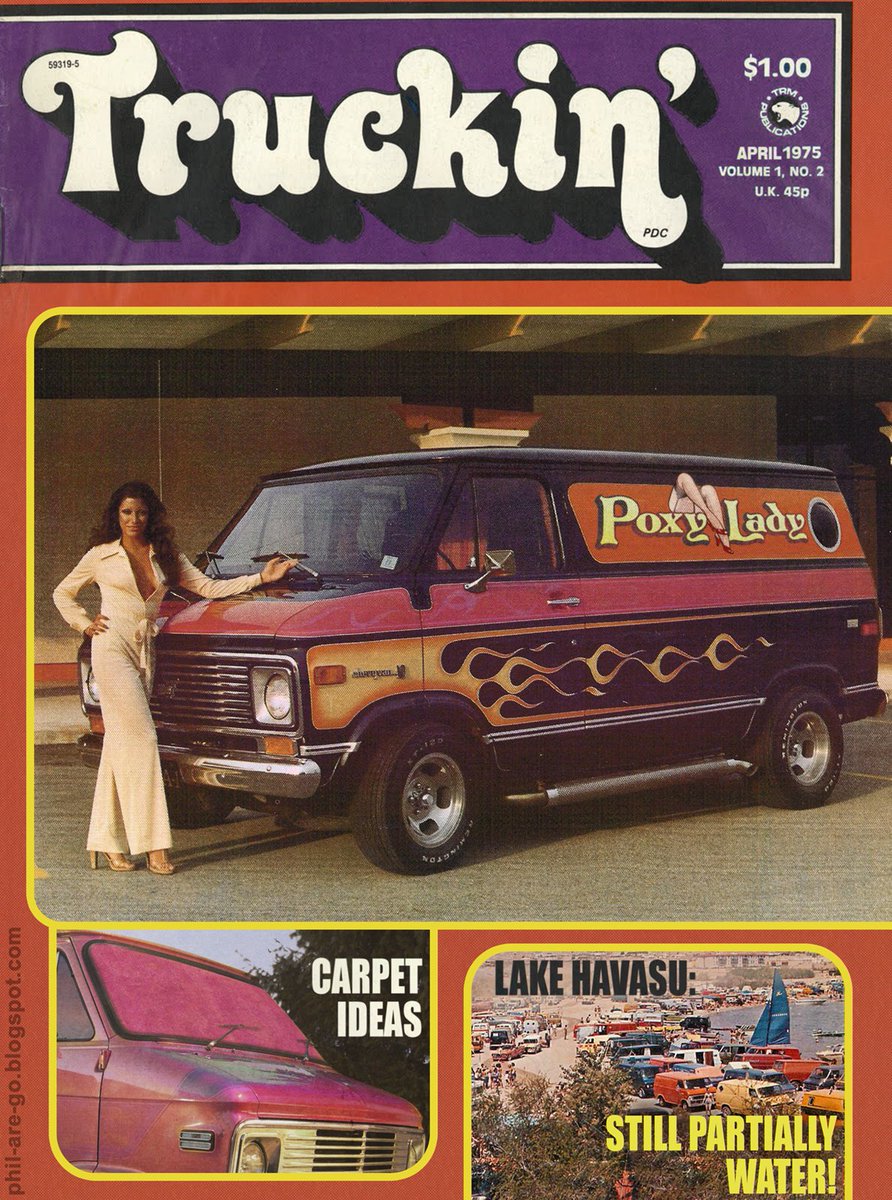

A range of magazines also sprang up to provide design inspiration, as well as letting the lucky few show off their radical wheels on the cover.

Brands were quick to muscle in in the scene too: Levi's, Coca-Cola, Yamaha and many others tried to turn young folks' heads in the '70s with a custom paint job and some chrome decals.

And it wasn't just vans: by the mid-70s even the humble station wagon was getting tricked out in a sick paintjob and sporting a portal window in the back.

So whatever happened to the custom street van? The same thing that happened to CB radio alas: the '80s arrived!

'80s kids didn't want to ride round in their dad's old pimped out Chevy van: they wanted something sleeker, sharper, more hi-tech. America was aspirational, and nobody really aspired to a shagpile bus painted like a prog rock album any more.

Auto makers pivoted their attention to the Soccer Mom and the family wagon. Vans were now practical, sensible runabouts for suburbanites juggling jobs, kids and recreation. Luxury was in, velour was out.

Will the street van return? Maybe, and hopefully not because it's all we can afford as a home nowadays! Once EVs reach critical mass it's only a matter of time before someone tricks out an electric van, with plasma screen walls and Bluetooth sub-woofers. We can't help ourselves!

But for now we'll have to make do with the memories. If this van's a-rockin' don't come a-knockin'!

More stories another time...

More stories another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh