Though early examples exist elsewhere, the skyscraper was truly born in America. And nobody shaped its development more than Louis Sullivan (1856-1924).

His greatest achievement was to synthesise older architectural ideas with an entirely new type of building.

His greatest achievement was to synthesise older architectural ideas with an entirely new type of building.

Modern construction methods and technologies made them possible, but it wasn't obvious how skyscrapers should look.

Sullivan lamented the "overeducated" architects who produced things like the New York Times Building. His Wainwright Building is a much more elegant formulation:

Sullivan lamented the "overeducated" architects who produced things like the New York Times Building. His Wainwright Building is a much more elegant formulation:

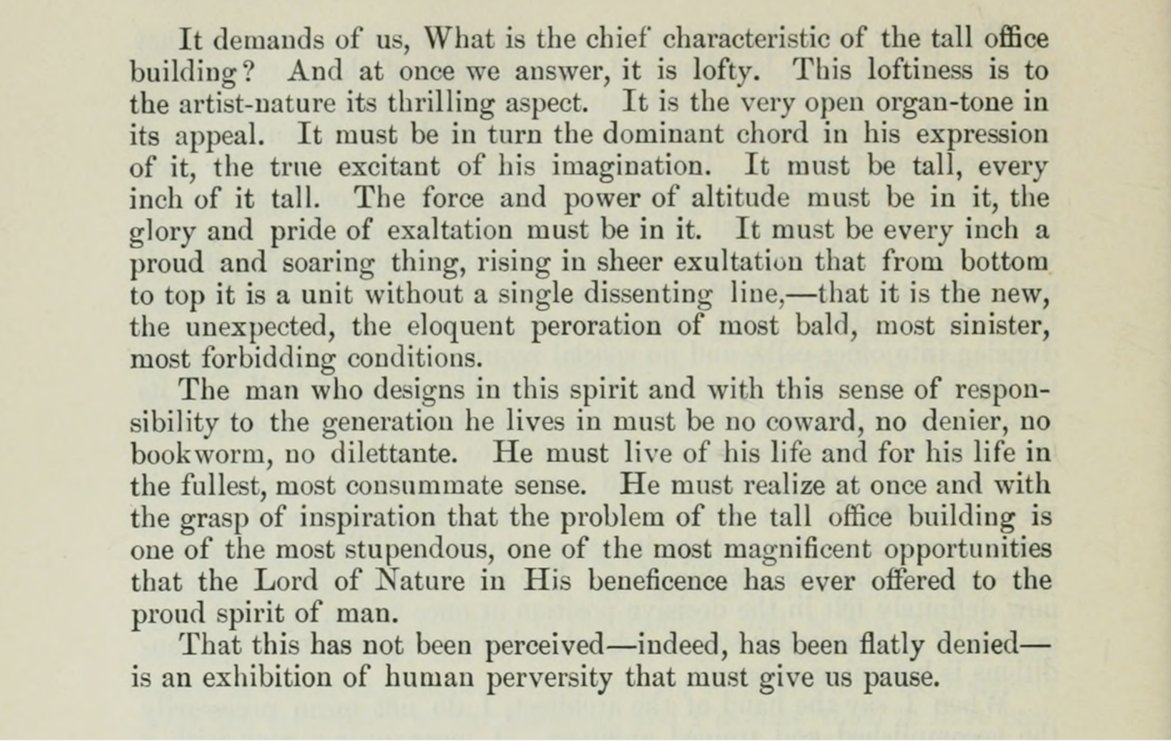

In an 1896 essay called "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered" Sullivan outlines his design principles.

Though the famous "form (ever) follows function" maxim is attributed to him - and he was the first to put it like that - it is an old architectural idea.

Though the famous "form (ever) follows function" maxim is attributed to him - and he was the first to put it like that - it is an old architectural idea.

Nor does it mean what we usually think.

Sullivan's point wasn't that architecture should be functionalist, excluding aesthetic considerations, but that aesthetic principles must be suited to the form of the building at hand.

Which, for skyscrapers, Sullivan saw as loftiness.

Sullivan's point wasn't that architecture should be functionalist, excluding aesthetic considerations, but that aesthetic principles must be suited to the form of the building at hand.

Which, for skyscrapers, Sullivan saw as loftiness.

In any case, Sullivan's style dominated for decades, and was the foundation for the many great Neo-Gothic and Neo-Classical skyscrapers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in America, even for the more futuristic Art Deco of the 1930s.

So what changed?

So what changed?

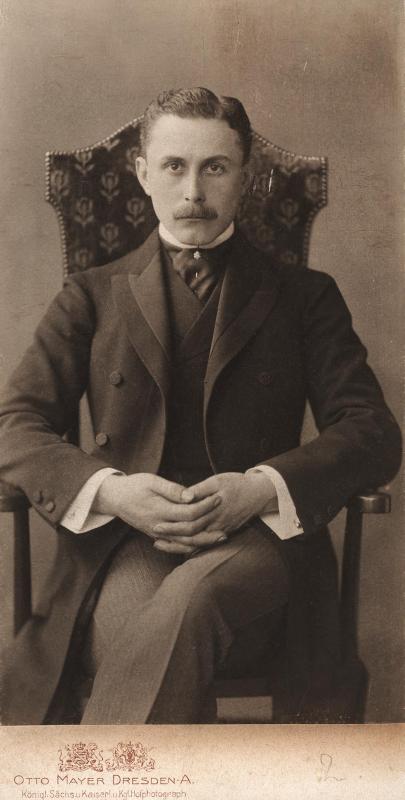

Well, in 1893 a disgruntled Austrian architect called Adolf Loos (1870-1933) came to the World's Fair in Chicago, where he saw Sullivan's skyscrapers.

Remember that Europe in Loos' time was dominated by revivalist styles, whether Neo-Gothic, Neo-Classical, or Neo-Byzantine:

Remember that Europe in Loos' time was dominated by revivalist styles, whether Neo-Gothic, Neo-Classical, or Neo-Byzantine:

Loos had seen the future, but what struck him most about America were its grain silos and water towers, which he saw while living in the countryside.

He considered them perfectly rational architecture, focussed on utility and nothing else, devoid of useless ornamentation.

He considered them perfectly rational architecture, focussed on utility and nothing else, devoid of useless ornamentation.

Loos returned to Europe and started designing things like the Steiner House, in Vienna. It may look modern, but it was built in 1910.

He believed ornamentation was a waste of money, time, and labour. It was irrational and ill-suited to the modern, industrial, machine age.

He believed ornamentation was a waste of money, time, and labour. It was irrational and ill-suited to the modern, industrial, machine age.

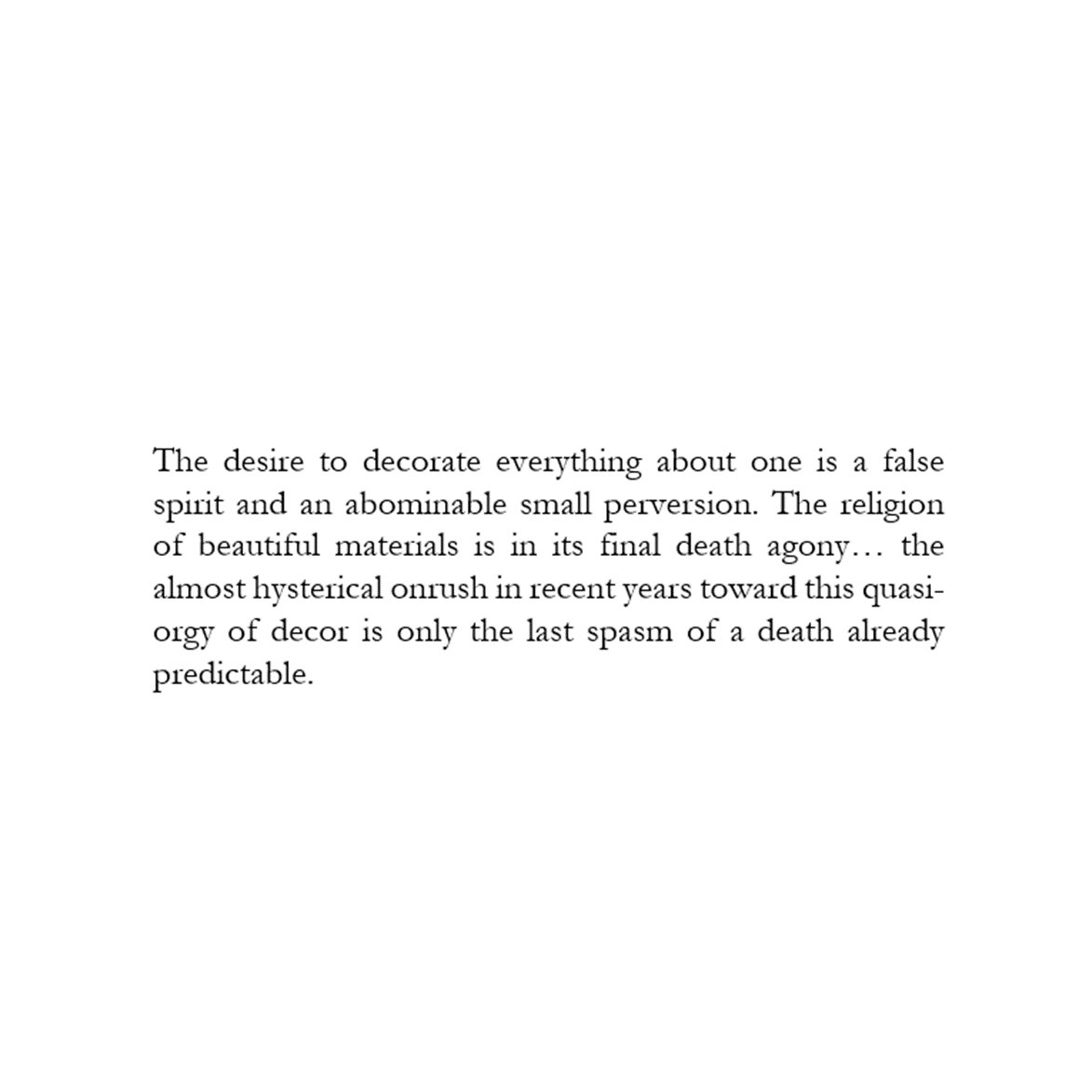

In his influential essay "Ornamentation and Crime" Loos said:

"I have reached the following conclusion which I give to the world: the evolution of culture is equivalent to the removal of ornamentation from utilitarian objects."

He took Sullivan's maxim to the extreme.

"I have reached the following conclusion which I give to the world: the evolution of culture is equivalent to the removal of ornamentation from utilitarian objects."

He took Sullivan's maxim to the extreme.

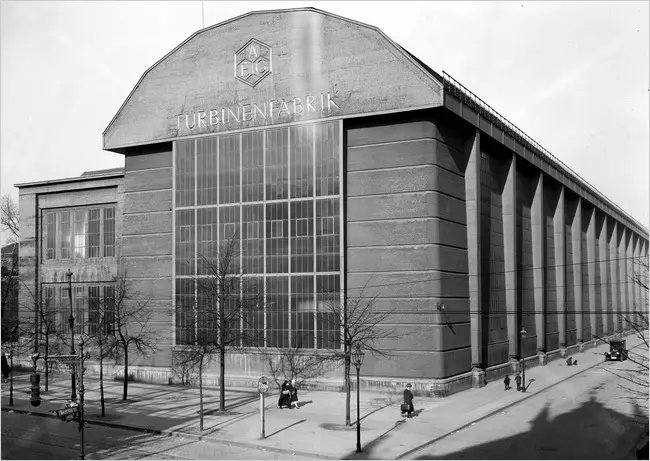

Parts of Germany and Central Europe had already seen attempts to reconcile modern materials, methods, and social needs with architecture, as in Behrens' 1909 AEG Factory, which appears like a form of industrial classicism, complete with stylised columns and pediments.

But Loos' more radical style triumphed.

His belief in functionalist architecture, devoid of ornament and colour, totally utilitarian and rational in nature, wielded a huge influence over an entire generation of European architects.

His belief in functionalist architecture, devoid of ornament and colour, totally utilitarian and rational in nature, wielded a huge influence over an entire generation of European architects.

For example, Le Corbusier (1887-1965) shared Loos' extreme views and based his famed treatise "Towards an Architecture" on Loos' ideas from Ornamentation and Crime.

The architecture of Le Corbusier seems like a more stylish version of what Loos was doing.

The architecture of Le Corbusier seems like a more stylish version of what Loos was doing.

The Bauhaus Design School, founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, also took much from Loos.

Encouraged by the German government, they sought to unify all crafts and arts together and reconcile them with mass production to create both quality and quantity for the public.

Encouraged by the German government, they sought to unify all crafts and arts together and reconcile them with mass production to create both quality and quantity for the public.

In 1927 the Deutscher Werkbund invited Bauhaus architects - including Gropius, Mies, and Behrens - along with Le Corbusier, to design a housing estate.

It was intended as an example of how to build cheap and efficient housing - and it prophecised the future.

It was intended as an example of how to build cheap and efficient housing - and it prophecised the future.

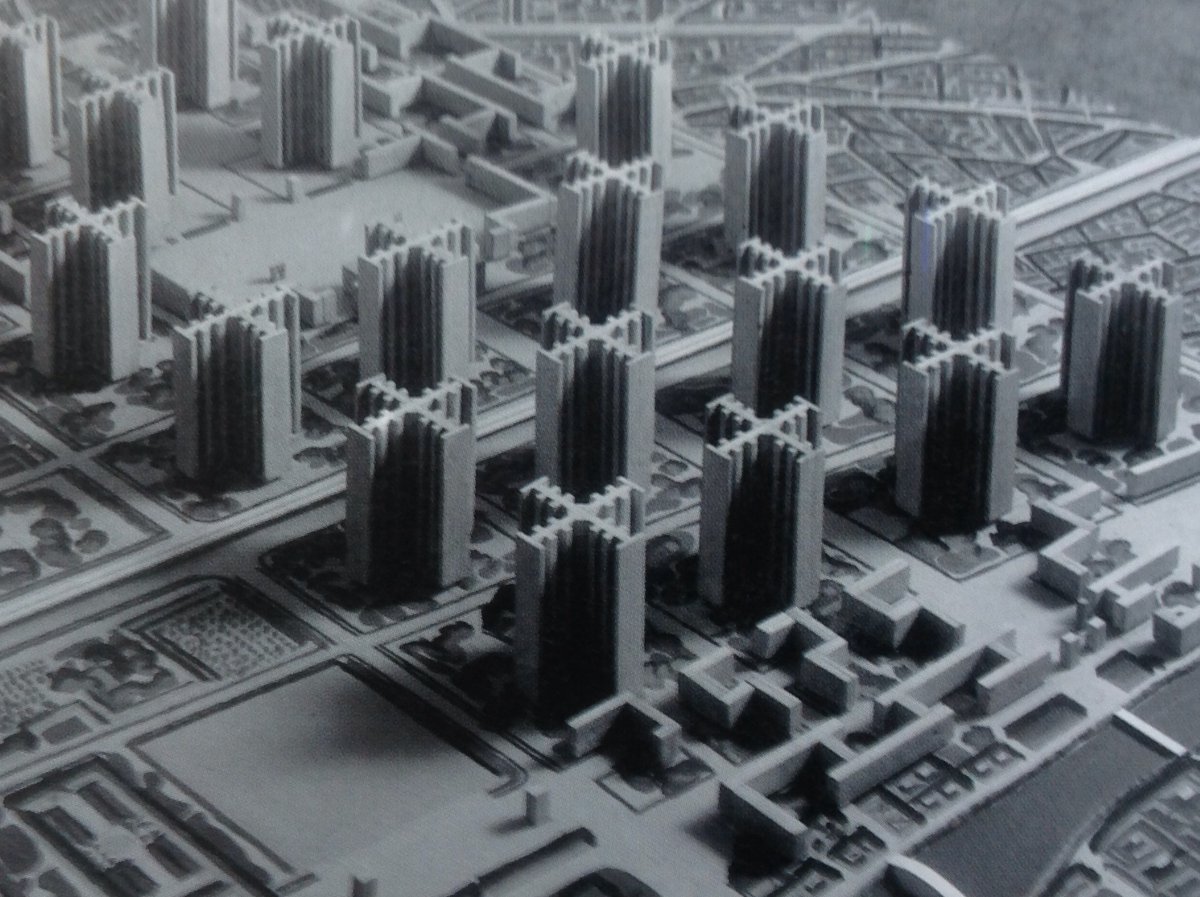

Underlying all of this was a futuristic urge, for Europe had been devastated by WW1 and its traditional architecture symbolised that.

They wanted to build a better world, hence their interest in urban planning. Consider Le Corbusier's model for a reconstruction of Paris:

They wanted to build a better world, hence their interest in urban planning. Consider Le Corbusier's model for a reconstruction of Paris:

Everything changed in 1933 when, under pressure from the Nazi regime and its attacks on anything avant-garde or modernist, the Bauhaus School was closed.

Its architects left Germany and took their ideas around the world, especially to America, where Gropius taught at Harvard.

Its architects left Germany and took their ideas around the world, especially to America, where Gropius taught at Harvard.

In the 1930s, of course, the Art Deco was still in vogue in America. But the Modernists didn't like it. Consider what Le Corbusier wrote about Art Deco, echoing Loos' belief that ornamentation was irrational.

And he was right - Art Deco turned out to be a short-lived movement.

And he was right - Art Deco turned out to be a short-lived movement.

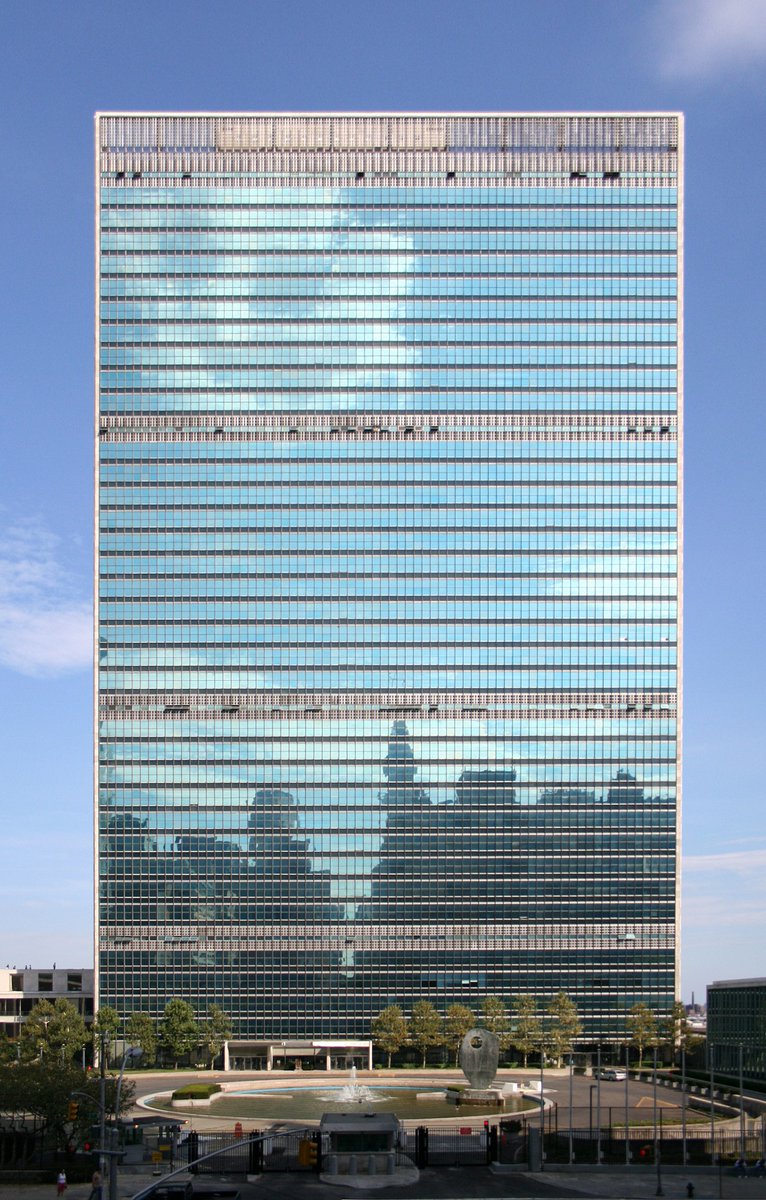

These modernist ideas - whether of Le Corbusier, Bauhaus, or the Scandinavian functionalists - had collectively become known as the International Style.

And in the postwar decades it became the style of the new world, one of global population booms and economic progress...

And in the postwar decades it became the style of the new world, one of global population booms and economic progress...

One of the leading members of the Bauhaus - and the final director of the school - was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969).

He, like Sullivan, wanted to create a style suited to the modern age no less than the classical had been to the ancient and the Gothic to the Medieval.

He, like Sullivan, wanted to create a style suited to the modern age no less than the classical had been to the ancient and the Gothic to the Medieval.

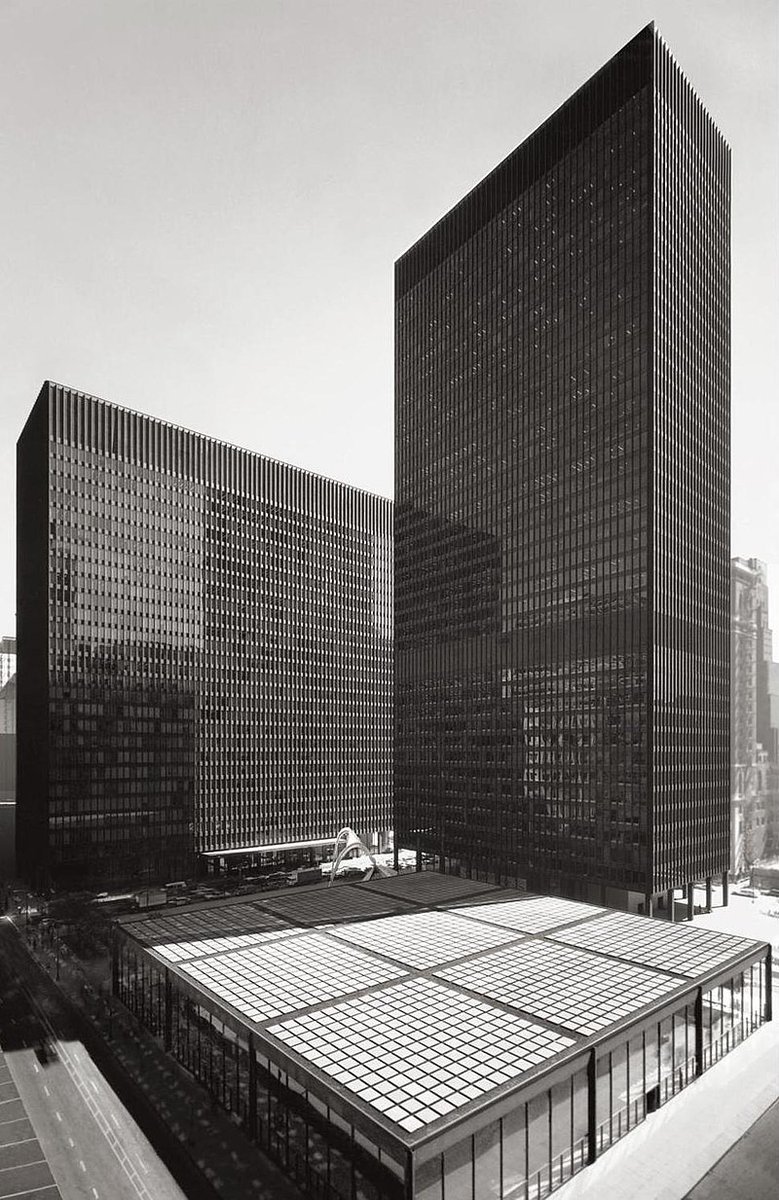

Mies settled in Chicago, and in 1958 he designed Seagram Building, the ultimate statement of this International Style and a far cry from those old Neo-Gothic and Art Deco towers.

His glass-clad skyscrapers would become *the* ultimate modernist form.

His glass-clad skyscrapers would become *the* ultimate modernist form.

Mies, more than any other, understood the potential of glass.

It could be mass-produced on an industrial level and used as a curtain-wall to clad large buildings cheaply. And, inspired by Loos, he believed that such structural materials had an innate aesthetic quality.

It could be mass-produced on an industrial level and used as a curtain-wall to clad large buildings cheaply. And, inspired by Loos, he believed that such structural materials had an innate aesthetic quality.

A wave of such skyscrapers appeared all around the world.

This was a universal approach indifferent to local architectural tradition or even climate, a functional and rational style suited to the modern age and devoid of any ornamentation or colour.

Modernism triumphant.

This was a universal approach indifferent to local architectural tradition or even climate, a functional and rational style suited to the modern age and devoid of any ornamentation or colour.

Modernism triumphant.

Variations and offshoots appeared, especially in the form of Brutalism.

Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil and Le Corbusier in India were both given the chance to design planned cities, where they experimented with unpainted concrete.

Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil and Le Corbusier in India were both given the chance to design planned cities, where they experimented with unpainted concrete.

Of course, even the International Style has now been replaced by a wave of more expressive, playful, and dynamic skyscrapers; gone are the sleek slabs of glass.

But the ideas of Loos, Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus, and Mies endure; their principles remain triumphant.

But the ideas of Loos, Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus, and Mies endure; their principles remain triumphant.

If you found this interesting then you may also like my free weekly newsletter, the Areopagus.

It features seven short topics every Friday, including architecture, history, art, and rhetoric.

Consider joining 50k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

It features seven short topics every Friday, including architecture, history, art, and rhetoric.

Consider joining 50k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh