This year I'm listening to Bach. I am a thundering ignoramus about classical music. I wasn't brought up with it, never really had much in my record collection (kids, we used to have 'record collections'). #yearofBach

For some reason, though, when I've heard some classical music and really responded to it and checked who it was by, the answer has often been Bach. So I thought I might go in big.

I got a massive box set for Christmas of everything Bach composed, some pieces in multiple versions, sections showcasing different performers, Bach's influences and his influence. Couple of hundred CDs (remember CDs?). It took me a week to rip everything to my computer...

I want to listen to Bach every day this year and try to properly understand what's going on. Classical music, all too often, turns into mush in my head because I'm never quite sure what I'm supposed to be listening to.

Brought up on pop/rock, if I'm being honest, I probably unconsciously expect a central melody line, find the proliferation of instruments a bit proggy, get lost in structures beyond the three-minute pop song...

(I'm probably overstating what a musical thicko I am, but not much.)

But Bach has always seemed to me fascinating because of a kind of (dare I say?) mathematical perfection to it that seems somehow like the DNA of the universe unfolding itself in sound. (Mixed metaphor, sorry.)

Bach seems both utterly mysterious and completely plain at the same time.

This may sound weird, but I want Bach to change me. I am looking forward to the effect of immersing myself in a new (for me) kind of music, restructuring the connections in my brain, finding a way through this music in a way that gives me new senses and sensitivities.

So I'm listening to a bit of Bach every morning. I started, at @DanElphick's suggestion, with some of the hits. Goldberg Variations, St Matthew's Passion, Brandenburg Concertos. To my astonishment, I didn't really recognise any of them (except Brandenburg No 3).

But, encouragingly, they seemed never anything less than thrilling. The Passion (esp. following the text in the accompanying booklet) was startlingly moving to me. I don't think I've ever been moved by classical music like that. (I realise everyone already knows it's moving...)

The Brandenburg Concertos were astonishingly sprightly. I love the story of the Margrave of Brandenburg off-handedly telling Bach 'do send me some of your music one day' and Bach sending the fucking Brandenburg Concertos. I mean... *mic drop*

The Goldberg Variations I found hardest to hear and most mysterious, the variations being subtle and having to keep both the individual variations and the whole shape in my head. When I come back to those, I'm sure they'll make more sense.

Probably not helped by my indecision about whether to listen to them played on harpsichord or piano (and which recordings). But I'm looking forward to immersing myself in their mysteries.

But since then, I've been listening to the Cantatas. I started with two a day but that's too much. I'm now taking one a day and listening to it a few times. I realise this will take most of this year in itself.

I'm 100% an atheist but, I tell you, these are the best argument for religious faith I've ever encountered. I thought they would be hard work: I sort of started there as a kind of make-or-break immersion. But they are gorgeous, pure, simple, transcendent.

Yesterday's Cantata was BWV 131 ('Aus der Tiefen rufe ich), an early work perhaps for a memorial service (I'm listening to them in order of composition not the church calendar). It builds to an extraordinary final chorus.

The sentiment that trusting in God's grace will redeem Israel is broken virtuosically into four musically-distinct sections, which then give way to a completely joyful fugue that stuck in my head all day.

This morning's Cantata was BWV 106, ('Gottes Zeit is die allerbeste Zeit') the 'Actus Tragicus', for a funeral service and it's quite shattering and exhilarating.

At the end of the 2nd section choral voices remind us that our covenant with God is that we must all die (Eccl. 14:17), but then a piercingly pure soprano voice rises above it to welcome unison with Jesus after death. And then the two sentiments daringly play out in counterpoint.

My recording is The Bach Ensemble, recorded in New York in 1985. The soprano is Ann Monoyios, whose voice is one of the most beautiful instruments I've ever heard. The whole recording is breathtaking.

Anyway, I'm aware these responses are probably naive. They may get less so over the year. I hope they will. I might occasionally add to this thread if anything strikes me. #yearofBach

This morning has been Cantata BWV 143 (‘Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele’). Much more fully orchestrated than the last two, to the point it felt bombastic at first in comparison. But the final chorale/chorus with their Alleluias are so full of joy I welled up.

And on further listenings many little joys. At the end of the 2nd section, as you wonder how he can resolve it musically, the soprano sings an extended flourish on ‘Vater’ that sorts it all out. And the bassoon (&organ??) under the 6th section twines round the strings gorgeously.

So today it's Cantata BWV 18 ('Gleichwie der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt') which fact fans will be keen to know I'm hearing in the Weimar version (i.e. without recorders). A much fuller text this one dealing with the need to protect God's word within us.

A superb opening for cellos in the bass and unison violas sets a dramatic tone for the whole thing. The central recitative - with alarming warnings against Turks and Papists! - is the most dramatic, the dire threats of the world being underlined by a chorus and then full choir.

Though it's framed either side by a beautiful bass recitative (with a gorgeous text) and a beautiful soprano aria ('My soul's treasure is the word of God') that feel more humane than the blood-and-thunder central section. And the spare accompaniment is enchanting.

Today and yesterday were the first two cantatas Bach composed in his new role as Concertmeister at Weimar: BWV 182 & 12. I don't know if it's because I read that but it feels like we have a huge elevation in grandeur and sophistication.

It's almost like the earlier cantatas embodied the sentiments in the words but now there's a larger almost theological structure around them, a greater intensity. The first Chorus of BWV 12 is extraordinarily emotional: both melancholy and terrifying. It's extraordinary.

The instrumentation is different, both in choice of instrument (the trumpet in the 6th part of BWV 12 is thrilling and new, I think) and in style (the oboe in the 4th part is joyfully melodic against the austere lesson about redemption in Christ).

And the choral writing is richer everywhere, I think: parts 7 & 8 of BWV 182 are gloriously confident and complex. The layers and rhythmic complexities of 'Meine Seel auf Rosen geht' feel unfathomably rich. I've listened to it five times and can't disentangle the parts!

I've just listened to BWV12 again and hadn't noticed the bass's jubilant little ascent at the end of section 5 on 'Ich folge Christo nach/Von ihm vill ich nicht lassen', which resolves the aria both surprisingly and with an expression of simple faith in the path to heaven.

It's BWV 54 this morning ('Widerstehe doc der Sünde') which is an injection of extraordinary drama from the very first note which strikes my ear as tense with dissonance. This propels us into the theme of the whole cantata: the dangerously insinuating deceptiveness of sin.

No oboe, no trumpet here, it's all driving strings which reminds me of Michael Nyman's main theme for 'The Cook, The Thief' (etc.), accumulating tension through repeatedly delaying the resolution. The alto's purity is goodness's imperviousness to Satan maybe?

Though this isn't smugly pious: the dark chord that bites twice at the final 'ist' of the text seems to caution against moralistic complacency, reminding us that Satan lurks everywhere, snapping at one's heels.

A question for y'all. How do you listen to recitative? It's not melodic like an aria. Is it all about the drama of it? Like a step on from underscoring a dramatic monologue? Feel like I'm not 'getting' it - or rather not sure what it is I'm supposed to be getting.

The final aria is sensational with the furiously busy strings and (what I'm learning to call) basso continuo, constantly seeming to fall away in a series of chromatic cadences, over which the alto's flourishes seem to be battling. Exhilaratingly dramatic!

Today it's BWV 172 ('Erschallet, ihr Lieder') which is different again. It almost sounds like, right after being appointed to the Weimar Court, Bach is showing off his range. After yesterday's high drama and Wednesday's emotional intensity, this begins brash and courtly.

But in the 4th section, suddenly we're in a world of subtlety and searching, the insubstantiality of the Holy Spirit inspiring some sinuous smoke-like musical wanderings in the strings and voice ('durchwehet').

The 5th section is another surprise. It's, well, it's a love duet between the soul and the Holy Spirit! And there's an oboe twirling between these two lovers. Quite the menage a trois. The harmonic layering is endlessly rich but never haunted by minor-key doubt. Amazing.

It’s Saturday so it must be cantata BWV 21 (‘Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis’) which is a monster, almost three times the length of any of the previous ones (not quite sure why). Also he rewrote parts of it giving the soprano parts to the tenor so I’ve listened to those too. 😇

The length makes it harder for me to hold the whole together but also there are some huge contrasts here. The first aria (section 3) is intensely moving, a beautiful sad melody introduced by the oboe and picked up by the singer. The emotion and the elegance in perfect balance.

But there’s an aria duet between the Soul and Jesus that honestly I found hard to take seriously - at least when it’s between a soprano and bass, where it strikes my ear like a love duet from a Viennese operetta! I far prefer the version where the soprano’s replaced by a tenor.

There are lovely surprises throughout: a suddenly storm-tossed line in section 5 (‘Sturm und Wellen’) and the EXHILARATING fugal permutations in the second part of section 6 (‘daß er Eminem’s Angesichtes Hilfe…’). And actually the stylistic transitions in the first part of 6…

The Sinfonia is gorgeous too (though a bit disconnected from the rest? But I only felt that on 2nd listen, going from the end to the start). Part 9’s chorus is warmly immersive. The sprightly, liberated final aria (section 10) is irresistible. This musical journey is THRILLING.

Can I just point out that it’s AutoCorrect that inserted Eminem into the 6th movement of Bach’s Cantata BWV 21, not me. #meines #eminem

https://twitter.com/DanRebellato/status/1616731606269534209

‘My Heart Swims in Blood’ (‘Mein Herze schwimmt in Blud’) is the extraordinary opening line of Bach’s cantata BWV 199, which takes us on a heart’s journey from sin to redemption, from swimming in blood to the final aria’s ‘How joyful is my heart’ (‘Wie freudig ist mein Herz’).

The journey’s a simple one but wrought with beautiful subtlety from the darkly dramatic in media res opening recitative which plunges you straight into despair to the almost literally dancing final aria.

The 2nd section (question: do you call the sections of a cantata “movements”?) has a lovely text framed by a wandering theme on a forlorn oboe which seems to sound more hopeful in its final return (despite no change to the music?)

The second half of the cantata just gets lovelier and livelier. After an exquisite aria (sec.4) in which the singer throws themselves on God’s mercy we have a chorale with a bouncing flowing string accompaniment then a scampering recitative that frolicks on “fröhlich”.

And the final section is positively fizzing with exuberance, capering about in 12/8 time. The flow between the parts of this cantata seems particularly strong. A lovely Sunday morning experience!

Last week I wondered aloud how you listen to recitative, which seems neither melody nor speech. Today's cantata (BWV 51 'Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland') partly answers it because its short (1 minute) recitative in section 4 is this piece's most intoxicating moment.

Over a series of plucked strings which add tension, drama, even a certain menace, a hushed Jesus urges us to let him into our doors and, implicitly, our hearts. It's a magnetically intense moment at the centre of this otherwise quite brash piece.

Of course, I meant BWV 61, not 51...

The cantata 'Christen ätzen diesen Tag' BWV 63 was written to be performed on Christmas Day and the first and final movements are suitably rousing and festive choruses. What interests me is everything else...

I guess most British Christmas church services lean heavily on the big festive hymns: heavy on celebration and light on anguish and pleading with the Lord. This piece follows recent cantatas in the movement from anguished separation from God to redemptive oneness with Him.

This initially struck my ear as incongruous, but there must have been something exhilarating in post-Reformation Europe in the awesome power of directly addressing God, so a structure like this that underlines His terrifying power and transforms that into His infinite benignity.

This cantata isn't as elegant as some recent ones but there's some great drama, in the scratching cello(?) that paws the ground as the Lion of David's tribe is mentioned in the 2nd recitative. The sinuous searching oboe figure in the 1st aria is lovely, seeming to seek God.

Cantata BWV 152 ('Tritt auf die Glaubensbahn'). This is a little smasher. VERY different instruments, sounding like a little chamber orchestra. The opening sinfonia is delightful and best of all is the 4th movement Aria, which is as close to a song as I've heard so far.

My quest to understand recitative gets another boost with the 3rd section, going from the 'abrasive' tone of recitative proper to (what I think is called) arioso, a mellower, more melodic line, mirroring a textual move from worldly sin (boo!) to salvation through faith (yay!).

Having got used to these things ending in the choir singing together, it's a surprise to end, as here, in a duet (Jesus & human Soul). The surging cello bass accompaniment and the instrumental themes returning build it up though it's still a low key - albeit elegant - conclusion.

The 2nd movement of Cantata BWV 158 ('Der Friede sei mit dir') is delightful and thrilling. Over a walking continuo on the organ, the bass sings an elegant aria with a busy and frisky violin dancing around it and is answered by a HAUNTING angelic unison chorale. Sheer bliss.

The 2nd recitative, like yesterday's(?), turns generously into arioso, an effect I'm starting to love. I'm also appreciating the recitative as a shift of gear and intensity. The final chorus I maybe didn't love, but that 2nd movement is just fantastic. Imma listen to it again.

Bach seems to have had access to better writers when he joined Weimar. Cantata BWV 31 ('Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret') has a much richer, more elegant text than earlier. 'Last hour, come forth, and close my eyes' is about as appealing as the embrace of death can get.

Musically, this cantata begins with a jubilant sonata, full of exciting touches that get the heart pounding and is then topped by a truly extraordinary chorus, beginning with a shout of 'Heaven laughs' and tumbling through fugues, chorales, and canons. Just wonderful.

It then narrows down to singular voices in arias and recitatives, a new focus on individual redemption. I'm understanding (?) the 'harshness' of recitative as conveying the challenge of God against earthly sin, as the rounder arioso style is linked to heavenly redemption

... which then leads into a more jubilant aria. In this cantata there are three pairs of recitative & aria, for bass, tenor and soprano, the voices literally and metaphorically ascending.

This culminates in the glorious final aria (sec.8) where the soprano (Gillian Keith sounding gorgeous in my recording), her voice dancing with an oboe figure, the whole thing transcendent. 'Let me be like the angels' she sings and she has her wish.

All that's left is for a short celebratory chorale to take us to the welcoming arms of heaven and we're done. This cantata is less than half an hour but the whole journey feels epic and magnificent.

After a weekend away, I return to my #yearofBach with BWV 165 which follows the previous couple in shaking up the format of the Cantata. This has three pairs of arias and recitatives capped off by a very short chorale.

The effect is theologically intense, a series of dense, taut articulations of the promise of being baptised in Christ, but with an agonised admission of the continual labours required from throughout life to refrain from sin.

Unlike the previous cantata (BWV 31), which ascended, the three arias descend the vocal range from soprano to tenor, suggesting the pull of earthly sin. But alongside that are three bass recitatives, all dramatic but shot through with melodic touches to convey divine goodness.

The opening aria is full of light and joy, its fugue-like strings crowned with a thrillingly flighty soprano ('Wasser' and 'Lebens'). I see from the sheet music that the second vocal line of the aria (bars 18-25) is based on the first (9-13) upside down! bach-cantatas.com/Scores/BWV165-…

The leaps upward in the vocal melody (and accompanying strings) in the second aria are like sparks from a fire. In the third, the full strings saw up and down in a tone, to my ears, of fearful beauty.

In section 4, the final lines of the recitative 'revives me when strength departs' is echoed by the strings seeming to fail in their strength, falling silent. This is an intensely serious cantata, more persuasive about the temptation than redemption.

Cantata BWV 185 hits my ear unevenly. The 'message' of this cantata is far more joyful and optimistic than most recent pieces and the best moments are full of light. The opening aria duet is heavenly, with the trumpet entwining with the soprano and tenor with force and beauty.

I'll be honest, I'm still learning to love the alto tone and in this recording I find the 1st recitative a little off-putting, though the alto aria with its generous string accompaniment and obbligato oboe is just lovely.

The bass recitative is stirring and leads into a punchy bass aria. The mixture of rhyming couplets and the frequent return to 'Das ist der Christen Kunst!' gives it a slightly operetta quality - a retrospective connection, of course, but it was hard to get G&S out of my head...

The strings that open it are arresting, though, and it takes us to the final chorale which has a lovely mixture of ascent and finality as we plant our flag in the summit of God's grace.

Well now. After, I'll admit, being left a little cool by the last two cantatas, today's is absolutely sumptuous. It's BWV 163 ('Nur jedem das Seine') and it's bursting with melody and scampering, driving strings...

from the opening aria in which the incipit is first articulated in the violins, then the basso continuo, then by the tenor, all in a series of lovely fugal echoes. Then there's a wonderful overlapping cello part driving the bass aria (sec.3), which is just EXHILARATING.

The singing on this recording (conducted by Masaaki Suzuki for the Bach Collegium Japan) is gobsmackingly lovely. Stephan Schreckenberger's bass is a rich, warm, humane voice you could take a bath in.

Aki Yanagisawa (soprano) and Akira Tachikawa (countertenor) have the most gorgeous recitative duet (recitative duet? I know right??) and then a piercingly lovely aria, both voices going sky-high but maintaining a heart-melting purity of tone.

That recitative has a number of different tones and styles in it, shifting pace and attack and maintaining in invention and excitement. The aria is magnificent, the intricate ascending duet seeming to capture human separation from and unison with Christ.

After that the chorus is a kind of palate-cleanser in its stately simplicity and elegance. All in all, one of my favourites so far.

Yesterday was Cantata BWV 132 and it's again full of generous musicality and startling variation. The opening aria is irresistible, with the soprano's exuberant coloratura fluttering over a rich joyful chamber orchestra. My recording's DIVINE soprano is Brigitte Geller.

The other most striking section is the bass aria (sec.3) which opens with this arrestingly dramatic figure on the bc & strings; then the vocal comes in with 'Wer bist du?' (Who are you?) in a version of the same figure. Thus that theological challenge permeates the whole aria.

I'm thrilled (to refer to my usual musical choices) by the way that angular motif sounds like the sort of thing a post-punk band would base a song around. The insistence of that 'riff' is here singling out every christian in the church somehow directly.

I mentioned a few days ago that I was finding the alto voice quite hard to love, but it starts to unlock for me here. There's a kind of weeping tone to it which, in the recitative (sec 4), with its dragging violin chords) is very affecting...

... and then in the aria is counterpointed by a joyfully 'free' violin, fiddling away exuberantly, perhaps suggesting the cleansing baptism possible, against the singer's anguished imperfection. He's good, Bach, isn't he?

Today's has similar exuberance. It's BWV 155 ('Mein Gott, wie lang, ach lange'). It begins, admittedly, in movingly dramatic despair with a desolate soprano recitative which flickers with hope only for a moment on the 'wine of joy' before sinking back.

But section 2's aria duet is enchanting, full of light and joy, the bassoon parping along amiably underneath with some virtuosic ultrafast runs and some huge leaps up the stave. The canonical structure of the duet is jubilant, glassily sublime when they sing together.

The bass recitative (sec 3) is both stern and reassuring, never leaving melody behind for long, giving it a more-than-usually kindly feel that underlies its message that Jesus might be present for you even when He appears most absent.

As delightful as the aria duet is the soprano's aria (sec 4). Over a poised dotted-rhythm string accompaniment filled with enthusiastic trills and majestic chordal passes, the singer urges herself to loving arms, ecstatically approaching the top of her range (top G?).

The soprano I'm listening to is Midori Suzuki for the Bach Collegium Japan and her voice has a joy and purity that almost makes me cry; in fact, a few more times and I think it will do. Anyway, another thoroughly beautiful cantata that is making my life better.

I struggle a little with Cantata BWV 161 ('Komm, du süße Todesstunde') which expresses an intense longing for death in the most physical of terms, which seems theologically austere (though in the early C18 I guess imminent death needed to be accommodated in various ways).

So the text - which is imagistically very rich (lions, comets, etc.) - seems to my C21 ear rather brutal, though it does build to chorus and chorale that expresses this longing for the moritifcation of the body in gentler terms.

It's all musically more austere, too, at least compared to yesterday's Cantata which seems like Rodgers & Hammerstein in comparison. That said, it can be lovely. Recorders are the instrumental stars here (who knew?). They're on almost everything adding tranquility and grace.

This is immediately clear in the instrumental opening to the first movement where they twine with the strings and the voice in an inexpressibly moving way. They seem to me interestingly both angelic and human...

In fact, I wonder whether the non-reed woodwind of the recorder, sounding closer to breath than, say, oboe or bassoon, is meant to evoke a humanity? In the tenor aria the tremendous yearning ('Mein Verlangen') sounds to me picked up by recorders in the following recitative.

They and/or the strings add a tumbling downward motion - perhaps imagining death? - to the 1st, 3rd, 4th & 5th movements (with a corresponding upward musical motif in the 4th as rebirth through Christ is evoked). The strings dramatically rush us towards death in the 4th.

I've found this one slightly harder to get into that the last few, perhaps because of its unappealing death wish, but musically it's haunting and elegant even in its uncompromising manner. I will come back to this.

Cantata BWV 162, though, is quite another story. We're deep in the parable of the wedding feast (Matthew 22) in which humanity is invited to a wedding and some refuse to come and others turn up inappropriately dressed. This piece begins very dramatically.

The singer appears to be a guest at the wedding, terrified to recognise ('Act! Ich sehe' is the motif throughout) the mixture of sinfulness and grace among the guests. The music is sumptuous - as befitting a royal wedding - but also stern and regretful.

At first, I thought - maybe intentionally? - this was the guest who will be thrown out. But it's a bass part, usually the voice of Jesus or righteousness, so probably not and he observes sin from a distance. It places us right in the middle of the drama though, thrillingly.

The second aria (sec 3) is apparently missing some instrumentation but my recording (John Eliot Gardiner) has oboe and recorder(?) added very persuasively. It's another frankly erotic desire for Christ ('I hunger for you... come, unite with me') and thoroughly beautiful with it.

The two recitatives on either side of it first (sec 2) wonders that poor humanity has been invited to such a feast and then (sec 4) is concerned that they have nothing to wear. I find the allegory confusing though: are we invited to this wedding as guest (1) or as bride (3 & 4)?

The 3rd aria is an alto-tenor duet, exulting that our faith has been rewarded by appropriate wedding attire. The scratchy, busy string continuo picks up the majesty of sec 1 over which the voices unfold beautifully. The final chorus is happy ending to this anguished sequence.

Well now! I've just been listening to Cantata BWV 22 and it's extraordinary. It's a kind of gloss on Luke 18.31-33 in which Jesus, leading the disciples to Jerusalem, tells them, basically, that he will be arrested, scorned, and killed but they don't know what he's talking about.

This cantata expresses a desire to understand Jesus, to be freed of assumptions and prior understanding, to be open to Him. The journey of the cantata is from turbulent confusion to radiant joy.

The opening chorus is tempestuous, the instrumental motif a series of cascading descents signalled at the beginning, suggesting both Christ's death and perhaps the falling short of the disciples' understanding.

The tenor sets the scene, the bass picks up the story, with those cascades foreshadowing what is to come, with occasional crunchy chords seeming to warn of danger (see the one at the beginning of this word).

Then an almost (but not) chaotic fugue from the choir expresses uncomprehension, with the words 'was' and 'das' ('what?', 'things'?) almost spat out in a hubbub of musical questions.

I've discovered that I just have to admit on this thread that I don't get something and it seems to unlock soon after. A few days ago I said I found the alto voice hard to love, but the alto aria (sec 2) is lovely. Claudia Schubert is the piercingly beautiful singer.

It's a very elegant aria with a fascinating moment where the alto hits the word Leiden (Passion, the very thing the disciples don't understand) with - I think! - an A rather than the G we expect? And everything is unbalanced for a moment as it takes 3 bars to extricate ourselves.

The bass recitative is rich and rounded, transitioning from the pain of incomprehension to a scampering joy in the very last line. This sets us up for the absolutely CAPERING second aria (sec 4) with busy, fluttering strings and the main motif passing between singer and strings.

Againts the first section's downward motif, we're now hearing lots of upward movement and in the final chorus, with a very insistent semiquavering string accompaniment, we put ignorance behind us. This is fantastic stuff.

I'm amid cantatas heading towards Easter, that challenge us to prepare for the Passion. BWV 23 ('Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn'), like the last one, takes us on a journey from unseeing to acceptance. We open with the blind man from Luke 18 begging Jesus for mercy.

That call for mercy resonates through the four movements. The first is, for me, the most thrilling, with it insistent triplet figure followed by a dotted phrase and descent, under an aria duet, the whole having a deeply beautiful and sombre mood.

The recitative (sec. 2) opens with a dramatic series of chords that sharply changes the tone as the blind man begs Jesus not to pass by (and simultaneously the cantata implicitly asks us not to pass by and then turns us all into the blind man).

Unusually we only have one aria-recitative before we end with a chorus and chorale. These are progressively jollier, the interplay of the voices in sec 3 beautiful and sprightly and then the final Chorale taking us through musical variations in style that hold intense interest.

It's both solemn and celebratory; even the frisky tone of sec 3 doesn't seem frivolous, but weighted with faith and it's challenges. The instrumentation is rich and full, oboes doing some gorgeous work throughout.

Today I listened - rather hastily (it's been busy) - to Cantata BWV 59. It's an odd one, the chorale is 3rd out of 4 movements, framed by a recitative and aria. In my recording, John Eliot Gardiner has added a second chorale, which feels necessary.

The most magnificent bit is the opening, a duet where, unusually, soprano and bass work together fuguing their way through Jesus's words in John 14.23. Generally Bach gives these words to the bass alone (so what the soprano's doing here?). But it's undeniably gorgeous.

Their voices entwine like vines, helped too by a rather marvellous instrumental arrangement that includes brass and timpani, so it all feels extremely powerful. The meticulous variations and permutations mean it's exciting all the way through.

The chorale (sec 3) is very lovely too, feeling rich and full, partly due to the arrangement of the strings. I can't say I was particularly engaged by the recitative (though I've not had time to re-listen much) and the aria (sec 4) is good but an odd ending.

The chorale that Gardiner ends with adds a welcome note of joy to this cantata that urges, rather repetitively, the strength to choose heaven over earth. I don't know what the source of this chorale is, though. (Is it even Bach?)

Tomorrow's cantata - spoiler alert - seems to have 14 sections, more than any so far, so I'm looking forward to getting to grips with a new musical/theological structure.

Wow. Cantata BWV 75 is ASTONISHING. Bach has just been appointed cantor of a church in Leipzig. He was 3rd choice, the 1st turning them down, the 2nd unable to be released from his previous job. Is Bach here on a mission to prove he should have been 1st choice?

Structurally, it has 14 sections falling into two halves, surrounding a gospel reading (Luke 16.19 The Rich Man and Lazarus). Both halves end with a chorale, preceded by 3 recitatives alternating with 2 arias. The first half starts with a chorus, the second with a sinfonia.

The richness & variety of the music here is stunning. The recitatives are all short but powerful (sec 2 is almost shockingly dissonant), the arias rich, graceful and stuffed with irresistible hooks. The lack of arioso in the recitatives is for theological-musical contrast maybe?

The opening chorus, a setting of Psalm 22.26 is outrageously brilliant: stately strings introduce a mournful polyphony of increasing texture and complexity which then gives way to a sprightly and surprising fugue. It's completely delightful.

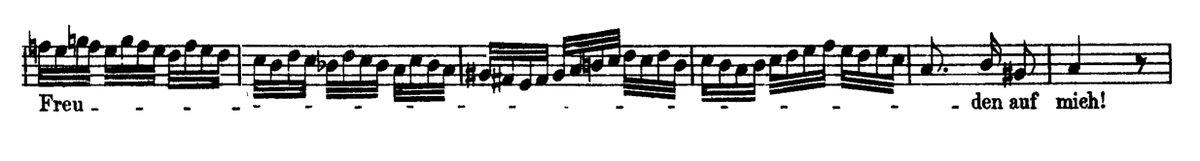

There are some joyous arias in here, all of them fleet-footed and extraordinarily catchy, with their sumptuous strings and vocal coloratura. In the soprano aria (sec 5) here's how the word 'angel' is elaborated.

In the second half, the instrumentation is augmented by a piercingly wonderful trumpet, first heard soaring out from the opening sinfonia, which restates some motifs from the chorus (good second-half opener, in other words! a kind of reminder of where we were).

(I realise in part why this musical style is familiar to me - the 'baroque pop' of the late 1960s is mainlining just this sort of thing. You could imagine The Left Banke putting words to this Sinfonia...)

The trumpet also gives the bass aria (sec 12 'Mein Herze glaubt und liebt') some extra magnificence, but in fact all four arias are quite wonderful. Instant ear worms, the passing of the main musical motif between singer and instruments invariably thrilling.

The chorale that ends both halves is full of delight, the string arrangement offering both energy and a kind of syncopated accent, picked up by the choir, the whole thing propulsive and joyful.

BWV 75 is an extraordinary piece of music. Almost show-offy in its apparently effortless brilliance. Nonetheless, I am amused to read the mild praise of a contemporary Leipzig newspaper: 'Mr. Bach comes here from the royal court, and performed his first piece to good applause.'

Genuine question: where can I hear some of these things in London being performed live? Who does these cantatas? Send me links.

And only a week later, the good people of Leipzig are given Cantata BWV 76, in some ways even more preposterously lavish and wonderful than the last. how did they react to its constant invention, its surprises, even shocks? Were they delighted or disturbed by their new Cantor?

To me the most astonishing movement is the first. A setting of Psalm 19.1,3, the theme is the immanence of God in all the works of nature and it starts with the basses singing alone and builds ... and builds... and builds.

By the end the texture and complexity is overwhelming, with different parts of the choir adding accents here and a crunchy harmony there, some trill of additional musicality while the very full orchestration propels us forward.

Part of the text declares 'There is no speech nor language where Heaven's voice is not heard' and the textual setting collapses at times into long non-verbal sequences, as if to find the ecstatic voice behind speech. It leaves me breathless.

Like BWV 75, this falls into 14 parts surrounding a sermon, 3 choruses, 4 arias, 6 recitatives and a sinfonia. The recitatives here far more arioso than last time; last time God's grace seemed very distant, but this time it's all around us, hence the sweetness.

In the 1st tenor recitative, there's a particularly warm moment when 'heaven moves' and the voice restlessly stirs and undulates.

There are two quite strident arias, for bass (5) and tenor (10), that firmly but cheerfully renounce faithlessness, each with each main point ('Fahr hin' [Go away!] and 'Hasse nur, Hasse much' [Hate then, hate me!]) lending its verbal rhythm to the whole musical arrangement.

There's an arresting spikiness to the arrangements too, especially sec 10, though some coloratura in 5 sweetens things considerably. All of them are short, marking some swift changes of tone and approach.

The alto and soprano arias are gorgeous. The soprano aria has the sweet clarity of a child's lullaby, like the bass arias, the rhythm its verbal invocation ('Hört, ihr Völker' [Hear, people!]) rippling through the whole structure.

The alto aria, too, is enchanting, the voice entwining with oboe d'amore (which has a much mellower and more sensual sound than the oboe) and the viola da gamba (am yet to home in on its sound!) that seems as fresh as a spring day.

A meditative, gentle tone is set by the second half's opening sinfonia while the chorus that ends both halves is rich and full, the trumpets joyfully anticipating the melodic lines.

How did the choir of St Thomas's church cope with this? That first movement sounds to me - very much a non-expert - extremely challenging and requiring preternaturally talented singers. Did they appreciate what they had? It's simply extraordinary.

Look, BWV 75 & 76 were always going to be hard to follow. Today I listened to BWV 24 ('Ein ungefärbt Gemüte') which, in comparison, felt a little flat at first. On second listening, though, there's much to enjoy.

The opening aria blends the alto, strings, and continuo with refinement and elegance (allowing one to ignore the weird German nationalist lyric). It sets the tone, exhorting us to our best moral behaviour.

This is picked up by a pair of recitatives, one demanding honesty and the other railing against hypocrisy ('Heuchelei' in German, marvellously). Both of these are harsh but dissolve into very lyrical arioso at the end.

They frame, for me, the highlight of this cantata, the central chorus (sec 3), which, like the opening chorus of BWV 76, build towards a rapturously textured fugue treatment of the 'do as you would be done by' theme.

It falls into two sections, the first a not-very-strictly choral monophony before breaking exultantly into the future with a particularly triumphant entrance for the trumpet at some point, brassing away above the churning voices. Beautiful.

I wonder if the two-part structure is meant to suggest the moral reciprocity of the theme? With the fugue suggesting that we're paid back many times over by our good neighbourliness. Because look how rich and complex the fugal section gets!

Oboe d'amore enliven the tenor's aria before the fine closing chorale (what's the difference between a chorus and a chorale??) where a stately and syllabic unison choir is underscored and alternated by a double time accompaniment with grand effect.

How to listen to religious music if you are yourself not religious? I don't speak German but I am reading the translations as I listen, meaning I've deliberately sought out the explicit religious content, so I'm not complaining, but at times I feel snagged on the religion.

I say I'm not religious (I'm an atheist), though I was brought up in a Christian country and as a family we went to church for a while, went to a CofE primary school, and of course the stories, the KJV language swirls around and through me.

Some of Bach's cantatas seem unforgivingly harsh in their early-1700s Lutheranism in a way that I can find obtrusive. I remember one that was a deeply-felt longing for death that seemed alarming. But it's textual, not musical.

But the music doesn't seem quite as caustic or gloating as the words. Who's the medieval theologian who said one of the joys of heaven would be the chance to enjoy the sufferings of the damned? The words maybe agree, the music never.

Bach's music can be perturbed, fearful, triumphant, cautious, but it never seems to set itself contrary to the listener in the way the words (sometimes) do. Of course Bach's setting the words, so he knows what they say, but I always hear joy and magnificence even in admonishment.

These thoughts arose perversely because today's cantata BWV 167 seems to me joyously humane at every moment. The opening aria is enjoining us to celebrate God but the setting inclines more to the celebration than the urging.

The gentle string theme winds gracefully through the song, supporting a lively tenor solo with some exuberant coloratura and moments of dynamic drama. There's little sense of sinful tension, just a setting of the joy of accepting Christ.

You can tell - he says crudely - when Bach's having a glass-half-full day because the recitatives, as here (secs. 2 & 4), incline much more towards the arioso. The second of those rather wonderfully introduces the final chorale (almost in a 'one and only Billy Shears' style!)

The central aria duet is simply heaven. The theme is the simple reliability of God's word: what he says will be, will be. This is musically captured in a series of duos: the soprano and alto, the fugal style of the middle section, the singers & oboe.

The opening section states the theme, with supreme elegance, the moments of polyphony seeming to capture the echo of word and action. Then the middle section jerks us from ¾ into common time, with an irresistibly vivacious new motif.

That itself starts to cascade into shifted and echoing patterns with the two singers in continually shifting harmony and calling and responding, and sometimes purely vocalising. It's sensational and I had to interrupt the flow to listen to it four times in a row.

Though eventually we get to the final chorale which somehow tops even that aria by being so MAGNIFICENT, the voices proudly keeping to a stately syllabic rhythm while the strings saw away at quadruple time and the trumpet shines out.

The effect is constantly beautifully assertive while introducing deeply satisfying musical tensions that are resolved in slightly different ways throughout, so that somehow when you get to the end it feels exactly perfectly heart-swellingly RIGHT. Thrilling (even for an atheist).

So with Cantata BWV 147, I stumble on a hugely familiar piece of music. The chorale that ends to two halves is none other than the intro to The Beach Boys's Lady Lynda or, as I concede is slightly better known, 'Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring'.

Having not recognised anything by Bach so far (except for one of the Brandenburg Concertos), this was almost shocking. I note though, on second listening, that the triplet form of the music is prefigured in the soprano aria and then in the tenor aria, bridging the sermon.

The whole thing is terrific. Once again we start with a chorus that takes a biblical verse and disaggregates it exhilaratingly, the words collapsing into pure semiosis (as Kristeva might say). There are three versions that tug the words this way and that, always surprisingly.

This recording (conducted by John Eliot Gardiner) has real punch in the bass, which is lovely. Elsewhere, he doesn't shy away from the confrontational harshness of the music and message - for example in the early part of the bass recitative (sec. 4).

In fact, secs 2 and 3 are like bad cop, good cop. The tenor recitative saying we're wicked for not acknowledging Christ and threatening us with retribution; the alto aria encouraging us not to be shy about coming to God. I wonder how noticeable the genderedness of this was?

That said, the recitatives also have quite a lot of melodic arioso content (especially for the alto and tenor). In the latter, which answers the soprano aria's call to jubilate, we are in joyful praise of Jesus. The words ‘Opfer’ (offering) and ‘kräftzig' is extended richly.

In the former, the oboes snakily give us some sinuous wriggling as the singer tells of Jesus stirring in his mother’s womb. The recitatives make a very powerful musical contribution here, whereas in other cantatas I've felt they are doing narration or some preaching.

The soprano aria (sec 5) is enchanting, mysterious, its longing lyric captured in its repetition and the cycling spiralling while the violin dances along throughout, perhaps balancing the yearning with barely-contained joy.

We were away for the weekend and I thought it a bit selfish to take time away to listen to music, so I'm only now coming bach to Bach (see what I did there). And Cantata BWV 186 is a pleasant welcome back: it's very full in 2 senses. It's long (11 movements) & fully orchestrated.

The theme is doubt vs faith, though here he does not adopt the aggressive tone of, say, BWV 24 which sternly wags its finger at us many times. There's a wandering, cautious tone to the opening Chorus, which is very beautiful but also human-scale somehow

Then each movement seems to grow in musical and instrumental density, grandeur and thus in musical confidence. The Chorale that ends the two sections is jubilantly un-solemn in its tumbling fugue-like textures. The penultimate movement (sec. 10) positively dances with joy.

This intrigues me; the aria is textually about transcending corporeality ('when you are free from the bonds of the body' it ends) yet the dance rhythm of the aria seems a celebration of physical exuberance & it's a duet which places the aria between, not above, bodiliness.

But even the recitatives got the memo. The early ones express the complexity of knowing Jesus, especially given His humble incarnation, and these reasonable questions are set with an uncertain, human-level musical expression, without too much damnation.

Towards the end they get positively tuneful. The alto recitative (sec 9) sticks pretty close to aria-type melodiousness all the way through. It's not as irresistibly melodic as some recent cantatas, but a pleasing way to continue the journey.

Today I'm on Cantata BWV 136 which strikes a very Pauline theological note, with its paralleling of Adam's first sin and its corresponding washing away in the blood of Christ's sacrifice in the two recitatives.

Both of these recitatives are full of dire threats and warnings, though this doesn't really characterise the whole. Generally, I think, these admonishing cantatas tend to start with warnings about sin and end with joyful redemption, textually and musically. Not here.

The opening chorus is an invitation to Jesus to examine our purity of heart. It's a lovely, tumbling fugue with some beautiful held notes and strong accents on 'prüfe' (test) and three gorgeous rising singing out of 'Herz' from bar 36 , sounding purer each time.

The instrumentation is pretty full, too, giving it all a very celebratory quality with oboes and brass giving it all a sense of 'mighty heaven'. The joy of this carries us through the tenor's railing against hypocrites into the alto aria...

This took me a couple of listens to get into, but the basso continuo and oboe d'amore offer a sinuous and wandering accompaniment (it's a proper 'walking' bass line) to the main section which hauntingly tries to grasp the coming day of judgement.

I find the presto middle section where the singer joyfully predicts the annihilation of hypocrites a bit incongruous, to be honest, but we're quickly back to the uncertainty and serpentine first section.

I think the tenor-bass aria duet is the highlight for me. It's got some very lovely rhythmic setting of the text that emphasises some natural speech rhythms (listen to the restarting on 'Allein' [But...]). But there's also some flowing coloratura on 'great stream'.

The brief, mostly monophonic, closing hymn to the cleansing power of Christ's blood rounds everything off. It's maybe a more minor piece this cantata but I am interested to see the variations in tone between text and music that Bach's trying out.

I tweet (absurdly) my judgment that one cantata is a 'minor piece' and it's like Bach's spirit goes 'I'll show HIM' because today's cantata is BWV 105 and it's shatteringly good. The theme is the difficulties of accepting Christ in the face of Mammon.

This is expressed very beautifully through the whole arc of the cantata's six movements. I'll come back to the opening chorus later but the alto recitative (sec. 2) is unadorned (secco) given only a basso accompaniment.

It's cautious, nervous, fearful, but there's a sense of divine presence in the bass notes. This contrasts sharply with the following soprano aria which has no basso at all. Instead the voice and oboe waver together over a propulsively jittery rhythmic ostinato from the strings.

The theme is the wavering of the imperfect and sinful human soul and we hear it in the way the sinuous oboe, sounding so human, curls around the human voice, giving the whole thing an undecided quality, the lack of basso continuo suggesting the directionlessness of Godless life.

That makes it all sound rather conceptual and dry but in fact this strikes the ear like a piece of Baroque Pop. Imagine Michael Nyman arranging one of McCartney's more melancholy ballads...

This takes us into the bass recitative which is almost an aria, so rich and melodic is it. Unlike the first recitative, now it's sumptuously accompanied with strings & rooted by the basso continuo. Where the first recitative is fearful & worried, this is all confidence in Christ.

The final (tenor) aria contrasts sharply with the uncertainty of the first: now it could not sound more certain. It's a kind of fanfare dance, the words set definitively to land with conviction. Around a sensuous horn, the strings whirl exultantly in demisemiquaver flourishes.

Finally the chorale begins with the 1st aria's semiquaver ostinato on strings but, as the choir expresses glad confidence in Jesus, the pattern turns from semiquavers to triplet quavers to quavers and then crochets, giving the effect of slowing and calming and reconciling.

It's a very simple effect but it's dazzling, seeming to slow down time, clearing your mind. It's one of the most seamless blends of music and meaning yet.

But let me also say something about the opening chorale. First, it's outrageously lovely. The text is from Psalm 143.2 ('enter not into judgment with thy servant: for in thy sight shall no man living be justified'). The two clauses are treated separately...

The first clause is given a polyphonic treatment, in which it is sung in part or whole around 60 times. The second clause become an allegro fugue and is again sung approaching 60 times.

What intrigues me here, not for the first time, is the tension between meaning and the dissolving of meaning by means of music. The polyphonous repetitions of the words seem to me to abstract them from meaning (as any word repeated can come to feel strange in mouth and mind).

Forgive an academic diversion, but I think of Julia Kristeva. A French psychoanalytically-inclined feminist, she developed a theory of linguistic meaning, making much of the distinction between words' meanings and their 'music'.

She's drawing on Jacques Lacan's revision of Freud: in coming to maturity through the Oedipal phase we do not simply repress desire but also language. The formless pleasure in sound-making is now organised: we must now make sense & the pleasures of language are to be put aside.

For Kristeva (and others, like Helene Cixous) this repressed linguistic pleasure comes out in things like literature, jokes, songs, puns, and so on. But adult language use demands we make sense, speak clearly, communicate meanings.

For Kristeva, what is crucial here, is that this Oedipal emergence into linguistic adulthood is a repudiation of the mother (as in Freud) and an acceptance of the law of the father. In a sense, we pass from a feminine sensuous relation to language to a masculine linguistic

Why am I saying this? This cantata and many beforehand are explicitly exhortations to accept the Law of the ultimate Father: God. Yet in these opening choruses there seems to me a tension between the maternal musicality and the paternal meaning.

This is, it seems to me, an entirely productive and artistically thrilling tension, though perhaps a theologically complex one. Put (over) simply, the text insists on masculine psychic discipline and the music asserts feminine psychic pleasure.

Who knows if there's anything in this, but where everything else in this cantata seems thrillingly, magnificently unified, I find myself just as excited by its tensions and contradictions. What a journey this is!

It's Sunday morning which is a pretty good moment to experience the wrath of God, so I'm listening to Cantata BWV 46, which amplifies the reading from Luke 19.41-48 in which Jesus weeps over Jerusalem and casts the merchants from the temple.

The journey of the whole cantata is immensely exciting. The opening chorale begins calmly enough with a passage from the Book of Lamentations (1.12) 'behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow which is done unto me'.

The voices entwine hitting the words 'Schauet' [Behold] and with increasing and troubling dissonance 'Schmerz' [Sorrow]. We are to observe sorrow because the Lamentation is for the destruction of Jerusalem.

And then, in the second section, we are given that destruction. In a blistering series of dramatic and unexpected vocal lines, with repeated downward musical motifs, God's wrath is brought down on the listener. It's really rather terrifying.

I listened to it a few times, marvelling. At one moment I followed in the sheet music and the second section - 'un poco allegro' - is actually SO allegro that you're scrolling at speed to keep up. The instrumentation often doubles the vocal lines which adds to the power & terror.

It has some knock-on effects for the rest of the cantata. Perhaps sensing that this is hard to follow, the admonishing tenor recitative is extremely arioso, more lamentation (a repeated five-note figure on the recorder underlining the tears) than anger.

The bass aria mixes the ferocity of the opening with the recitative's melodic feel. The bass line rumbles threateningly, the trumpet triumphs, and the singer predicts the terrifying beam ('Strahl') of God's wrath in a near-impossible vocal flourish.

Later in the same aria the same idea expressed as 'Rache Blitz' [lightning of vengeance] is given alarming and menacing attention, with a surprising rising repetition. Sec 1 & 3 both use the basso continuo to represent God's vengeance which has an effect on the alto aria.

It represents a strong contrast with God's punishment - now it's a pastoral scene of Christ's protection - and there's is no basso at all. Instead oboes and recorders, giving it a lilting Elizabethan ballad feel to my ears, tell of Jesus gathering us to Him like a mother hen.

The serenity of the scene is only briefly ruffled by a quickening reminder of 'Wetter der Rache' [Storms of vengeance] where everything palpitates briefly, but the storm subsides quickly.

The lack of bass is, I think, cleverly prepared for by the end of the preceding recitative, which ends with a descending bass figure, perhaps to emphasise the threat that is about to be lifted.

The concluding chorus is joyous and hymn-like, with the recorders returning to flutter around the unison choir, perhaps in their lively movement a reminder of the earlier movements and their agitation, but the whole offering a vision of redemption. Lovely.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh