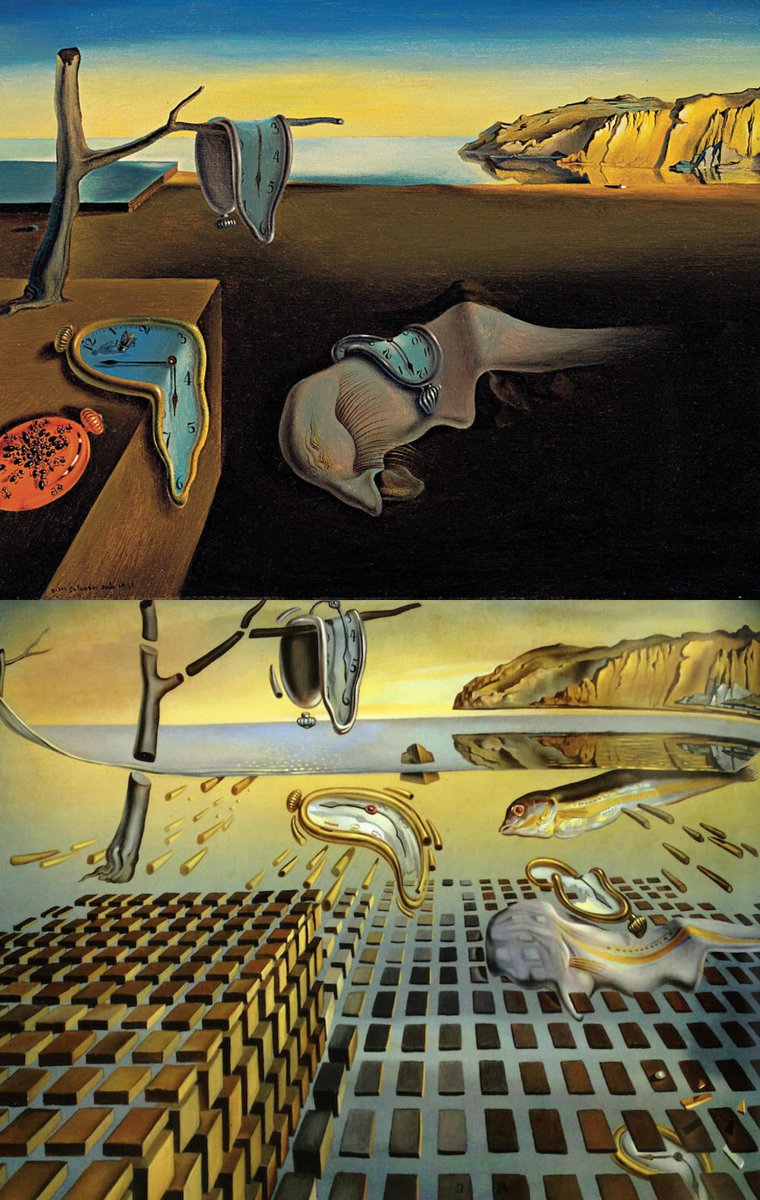

Why did Salvador Dalí paint those famous melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory?

And why did he paint The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory twenty years later?

And why did he paint The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory twenty years later?

Salvador Dalí was born in Catalonia in 1904.

Two events shaped his early life. One was the death of an older brother he never knew, also called Salvador. And the second was the death of his mother when Dalí was just sixteen.

These had a profound influence on his psychology.

Two events shaped his early life. One was the death of an older brother he never knew, also called Salvador. And the second was the death of his mother when Dalí was just sixteen.

These had a profound influence on his psychology.

From an early age Dalí proved himself a profoundly talented artist. This painting was made in 1913, when Dalí was only nine years old.

Such art, influenced by the Post-Impressionists, dominated through his teenage years.

Such art, influenced by the Post-Impressionists, dominated through his teenage years.

In the 1920s Dalí was introduced to Cubism and produced such works as Cabaret Scence, far from Dalí's now famous style.

He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid - where his talent for figurative painting became clear - but left before finishing his studies.

He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid - where his talent for figurative painting became clear - but left before finishing his studies.

Everything changed in the late 1920s when he visited Pablo Picasso in Paris and was there introduced to the Surrealists, led by André Breton.

They profoundly influenced his art - which rapidly took on its recognisable form - and he became the most famous member of their group.

They profoundly influenced his art - which rapidly took on its recognisable form - and he became the most famous member of their group.

The Surrealists had emerged in the aftermath of the First World War, shattered by primordial horror at the conflict.

And inspired by Giorgio de Chirico in Italy, who even before the war had starting exploring dreams, the Surrealists turned to the subconscious.

And inspired by Giorgio de Chirico in Italy, who even before the war had starting exploring dreams, the Surrealists turned to the subconscious.

The result, broadly, was a rejection not only of the civilisation that had caused the conflict but of the external, material world entirely.

Whereas art for so long had look outwards - whether at the ideal or real, even subjectively - the Surrealists journeyed inwards.

Whereas art for so long had look outwards - whether at the ideal or real, even subjectively - the Surrealists journeyed inwards.

The subconscious, the nightmarish, the phantasmagorical, the seemingly impossible; Dalí and the other Surrealists, like Magritte, channelled such forces in their work.

Subverting expectations, playing with illusions, disturbing, provoking, defying explanation.

Subverting expectations, playing with illusions, disturbing, provoking, defying explanation.

And in 1931 he created The Persistence of Memory, his most famous painting and the most famous work of Surrealism, apparently inspired by seeing a camembert melting in the sun.

It was, perhaps, the closest art has ever come to representing the strangeness of dreams.

It was, perhaps, the closest art has ever come to representing the strangeness of dreams.

It isn't surprising that Dalí was intrigued and heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud.

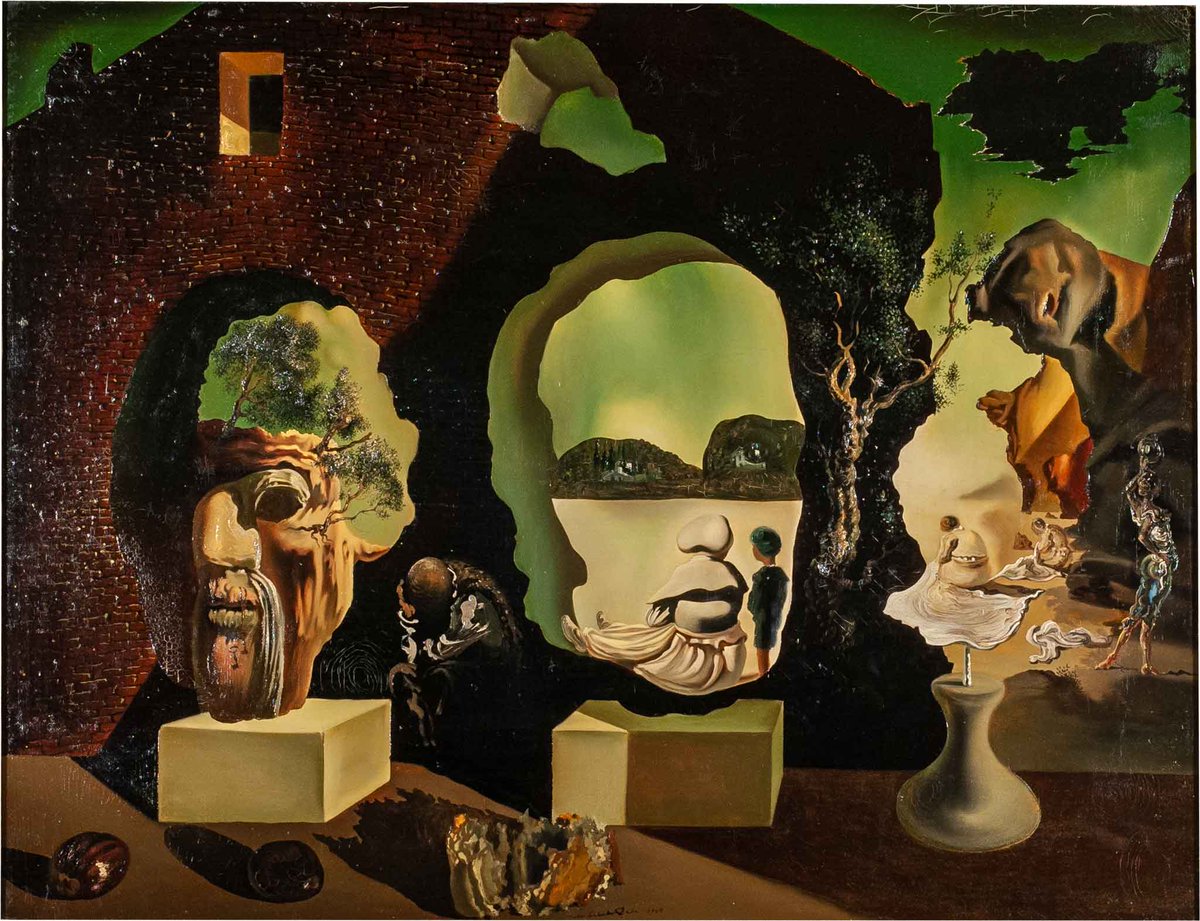

In Average Atmospherocephalic Bureaucrat in the Act of Milking a Cranial Harp - a typically bizarre Dalían title - he addresses feelings towards his father.

In Average Atmospherocephalic Bureaucrat in the Act of Milking a Cranial Harp - a typically bizarre Dalían title - he addresses feelings towards his father.

And here is a key difference between abstract art - which, making no attempt at being recognisable, is even if baffling not so disconcerting - and Surrealism.

Surrealism, by using the traditional artistic methods of representing reality, is unsettling *because* it is familiar.

Surrealism, by using the traditional artistic methods of representing reality, is unsettling *because* it is familiar.

Indeed, Dalí's greatest gift might be his draughtsmanship, his mastery of modelling and composition; it is up there with the great masters Dalí himself studied at the Museo del Prado.

Every detail is minutely, exquisitely crafted, resulting in a sort of stylised photorealism.

Every detail is minutely, exquisitely crafted, resulting in a sort of stylised photorealism.

And, of course, Dalí had a keen sense for powerful, striking, and disturbing imagery. But, crucially, he presented it with a profound clarity not so dissimilar from the artists of the High Renaissance.

His visual language was compelling and totally unforgettable.

His visual language was compelling and totally unforgettable.

Dalí's relationship with the Surrealists was strained - not least because Dalí believed art could be apolitical; his contemporaries, horrified by the rise of fascism in Europe, disagreed.

Consider Orwell's later critique of Dalí to see why his position was so shocking to them.

Consider Orwell's later critique of Dalí to see why his position was so shocking to them.

After the Second World War, during which Dalí and his wife had fled France for America, they returned to Europe.

And in 1954 Dalí painted The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, returning to his earlier masterpiece.

Only, this time, it was falling apart.

And in 1954 Dalí painted The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, returning to his earlier masterpiece.

Only, this time, it was falling apart.

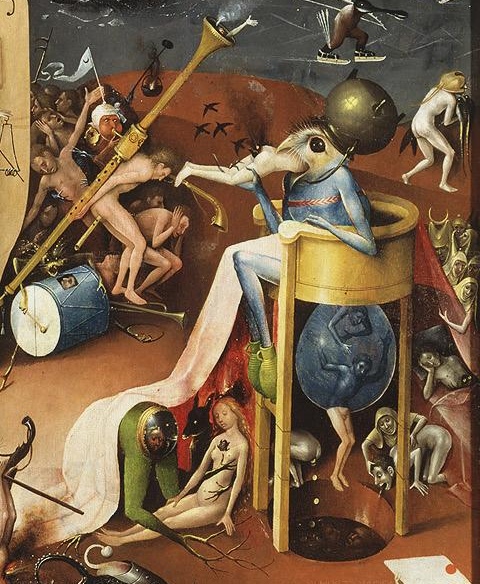

Surrealism as a self-defining movement may have only emerged in the 1920s, but its instincts are far older.

The Garden of Earthly Delights, painted by Hieronymus Bosch in 1515, is equally interested in the stranger parts of human psychology and unafraid of bizarre imagery.

The Garden of Earthly Delights, painted by Hieronymus Bosch in 1515, is equally interested in the stranger parts of human psychology and unafraid of bizarre imagery.

While in the 16th century portraits of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, composed out of everything from fish to fire, we see Dalí's penchant for constructing faces from other objects and his delight in the grotesque, even the comical.

What unites named Surrealism and such forms of proto-Surrealism is an exploration of the human psychological response to external factors.

For Bosch it might have been plagues, for Arcimboldo perhaps Renaissance philosophy, and for Dalí it was modern science.

For Bosch it might have been plagues, for Arcimboldo perhaps Renaissance philosophy, and for Dalí it was modern science.

The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory was part of his self-titled "nuclear mysticism" phase, inspired by nuclear physics, Einstein's theories, and the tensions of science and religion.

Disintegration pervades his postwar art; Dalí's inner world reflecting the outer.

Disintegration pervades his postwar art; Dalí's inner world reflecting the outer.

Dalí died in 1989 as one of the world's most famous, influential, and celebrated artists; one who had lived to see his avant-garde style conquer the world.

Among his most notable late paintings was The Hallucinogenic Toreador, from 1970.

Among his most notable late paintings was The Hallucinogenic Toreador, from 1970.

Though he is now largely viewed as a creative genius, one whose art - even if strange - is far from controversial, that was not always the case.

Once upon a time his work was, like so much of the avant-garde outside of their original circles in the 20s and 30s, scandalous.

Once upon a time his work was, like so much of the avant-garde outside of their original circles in the 20s and 30s, scandalous.

And, alongside his art, Dalí the man was a figure of deep controversy, not only for his famous political ambivalence but for his personality.

In 1942 he published an autobiography. George Orwell reviewed it two years later. Here's what he had to say:

In 1942 he published an autobiography. George Orwell reviewed it two years later. Here's what he had to say:

Orwell was personally digusted by Dalí but recognised his extraordinary talent.

And even though Orwell - who fought in the Spanish Civil War - had reason to criticise Dalí's politics, he refused to condemn him and argued that Dalí's sucess raised important social questions.

And even though Orwell - who fought in the Spanish Civil War - had reason to criticise Dalí's politics, he refused to condemn him and argued that Dalí's sucess raised important social questions.

Orwell was equally unimpressed by those who praised Dalí uncritically and those who rejected him at face-value.

Above all he was interested in the relationship between art and morals, between art and artist (whether they can be separated) and saw Dalí as a perfect case study.

Above all he was interested in the relationship between art and morals, between art and artist (whether they can be separated) and saw Dalí as a perfect case study.

That controversial reputation has since faded and Salvador Dalí has become a byword for creative genius.

He was, perhaps, the most technically gifted artist of the 20th century, and his unforgettable paintings are now among the most famous and influential in the world.

He was, perhaps, the most technically gifted artist of the 20th century, and his unforgettable paintings are now among the most famous and influential in the world.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh