Gothic architecture wasn't just a single style.

It had hundreds of versions, some strange and some beautiful, in different places and at different times.

So here is a journey through the world of Gothic architecture...

It had hundreds of versions, some strange and some beautiful, in different places and at different times.

So here is a journey through the world of Gothic architecture...

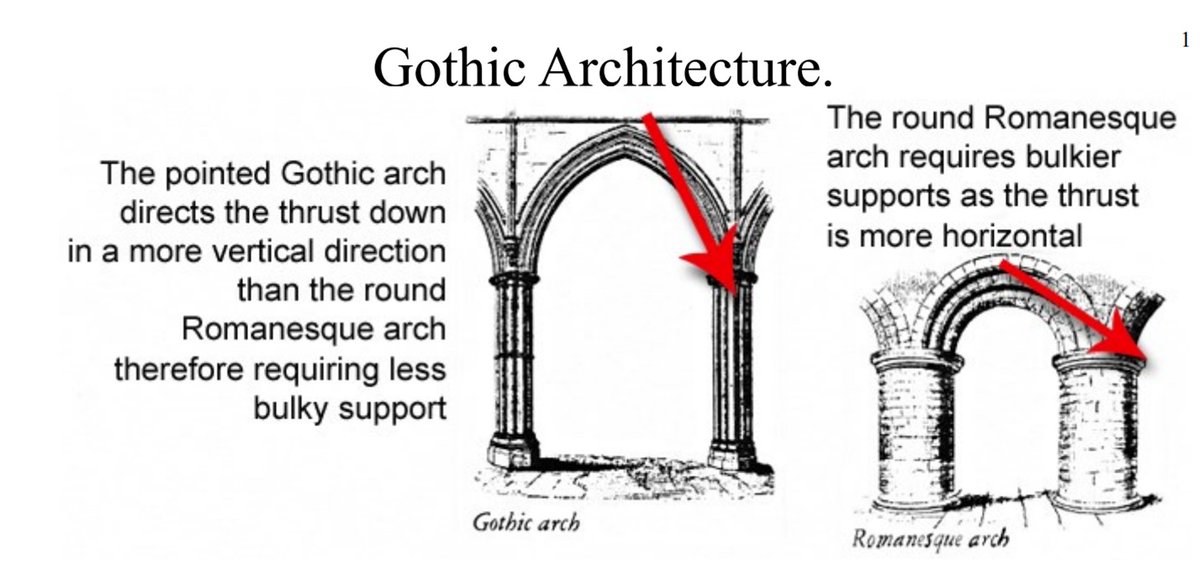

Gothic architecture first appeared in the 12th century, when the pointed arch appeared in Europe.

Until then churches and cathedrals had been built with the round arch. This style, in imitation of Roman architecture and its round arches, is known as Romanesque.

Until then churches and cathedrals had been built with the round arch. This style, in imitation of Roman architecture and its round arches, is known as Romanesque.

The pointed arch is much stronger than the round arch - buildings rapidly became taller, larger, and more complex.

Whereas structural concerns had once dictated how cathedrals looked, aesthetics soon took centre stage.

An architectural revolution swept the continent...

Whereas structural concerns had once dictated how cathedrals looked, aesthetics soon took centre stage.

An architectural revolution swept the continent...

The first phase of Gothic architecture in Britain was the Early English Style (1150-1250).

Windows remained slim and the overall design fairly simple, as embodied by Salisbury Cathedral. The tower, added later and more complex, contrasts with the simplicity of the older parts.

Windows remained slim and the overall design fairly simple, as embodied by Salisbury Cathedral. The tower, added later and more complex, contrasts with the simplicity of the older parts.

Next came the Decorated Style (1250-1350), so-called because it embraced detailing and complex, flowing ornamentation.

The Bishop's Eye rose window in Lincoln Cathedral and the crossing of Ely Cathedral capture this spirit, permitted by more advanced construction methods.

The Bishop's Eye rose window in Lincoln Cathedral and the crossing of Ely Cathedral capture this spirit, permitted by more advanced construction methods.

That was followed by the Perpendicular Style, unique to Britain, which lasted until the 16th century.

It replaced the curving forms of the Decorated Style with more austere vertical lines, exemplified by the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey.

It replaced the curving forms of the Decorated Style with more austere vertical lines, exemplified by the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey.

This emphasis on verticality, combined with a tendency for high walls and vast windows, resulted in buildings which were like cages, more glass than stone.

Elaborate, geometric fan vaulting was another common Perpendicular feature.

Elaborate, geometric fan vaulting was another common Perpendicular feature.

English Gothic architecture was heavily influenced by that of France.

There, too, the Early French Style was fairly plain in appearance - perhaps because of structural and technical limitations.

The result was a sturdy, unadorned monumentality.

There, too, the Early French Style was fairly plain in appearance - perhaps because of structural and technical limitations.

The result was a sturdy, unadorned monumentality.

The High Gothic style in France (1190-1250), is regarded by some as the pinnacle of all Gothic architecture.

It seems to mix the delicacy and elaborate ornamentation of later styles with the monumentality of what came before, a harmonious middle ground.

It seems to mix the delicacy and elaborate ornamentation of later styles with the monumentality of what came before, a harmonious middle ground.

Similar to the Decorated Style in England, the French Rayonnant (1250-1350) was less about size and more about refinement, with technical progress allowing for the construction of much larger windows with more complex tracery.

Embodied by Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

Embodied by Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

The Flamboyant style, which dominated in France thereafter, comes from the French word for flaming, a reference to the flame-like appearance of the design motifs used in its decoration.

The overall impression is of astonishing complexity, detail, and delicacy.

The overall impression is of astonishing complexity, detail, and delicacy.

The Brabantine Gothic was a form of Gothic architecture that appeared in the Low Countries. It was influenced by neighbouring traditions but mixed them in unique ways.

It placed particular emphasis on height, while retaining smaller windows and more restrained decoration.

It placed particular emphasis on height, while retaining smaller windows and more restrained decoration.

But there was also a great tradition of secular Gothic architecture in the Low Countries, spurred on by the guilds and merchant classes of its trading cities.

As in Brussels' Town Hall, these could be covered in elaborate decoration - but with that same Brabantine verticality.

As in Brussels' Town Hall, these could be covered in elaborate decoration - but with that same Brabantine verticality.

Much Iberian architecture in the Middle Ages was inspired by the Islamic architecture of the Moors, who had ruled the peninsula for centuries. The style is known as Mudéjar.

Design motifs - especially complex geometric patterns - were adopted from mosques and used in churches.

Design motifs - especially complex geometric patterns - were adopted from mosques and used in churches.

A highly unusual form of Gothic architecture also appeared in Valencia, epitomised by the twisting columns of its Silk Exchange.

The Plateresque is another Gothic substyle unique to Iberia; its name comes from the Spanish for silver because of the fineness of the ornamentation applied to its exteriors, reminiscent of silver filigree.

It also blended Renaissance, Mudéjar, and Flamboyant elements.

It also blended Renaissance, Mudéjar, and Flamboyant elements.

The Manueline was a Late Gothic style unique to Portugal, named after King Manuel I. Design motifs taken from Portugal's seafaring exploits were incorporated into its elaborate decoration, such as ropes, sea creatures, and navigational instruments.

Italian Medieval architecture, heavily influenced by the Byzantines, had never embraced the pointed arch and remained highly distinct from the rest of Europe.

Some Gothic influence is visible, however, in the facade of Siena Cathedral.

Some Gothic influence is visible, however, in the facade of Siena Cathedral.

And in Milan, which is in northern Italy and closer to Central Europe, a great cathedral was commissioned in 1386.

It took centuries to build and mixed countless Gothic styles - from the Perpendicular to the Flamboyant - with Renaissance elements; the result was totally unique.

It took centuries to build and mixed countless Gothic styles - from the Perpendicular to the Flamboyant - with Renaissance elements; the result was totally unique.

As the Renaissance swept Europe its neoclassical architectural style was not welcomed everywhere. In Bohemia it was resisted and Gothic architecture had a late zenith.

St Barbara's Church in Bohemia features a striking tented roof built in 1588.

St Barbara's Church in Bohemia features a striking tented roof built in 1588.

This style, unique to the Central European areas of southern Germany, Austria, and Bohemia, has been called "Sondergotik".

It is noteworthy for its unusual vaulting, which featured broken ribs and rather dramatic reticulation, as in Prague's majestic Vladislav Hall.

It is noteworthy for its unusual vaulting, which featured broken ribs and rather dramatic reticulation, as in Prague's majestic Vladislav Hall.

There's also the Brick Gothic, a broader movement rather than a specific style of Gothic architecture, in which bricks rather than quarried stone were used for construction.

It was particularly common in nations around the Baltic.

It was particularly common in nations around the Baltic.

And they are just a few examples of Gothic architecture's many interpretations. Every region and city - nevermind each country - often had their own unique varieties.

It should be mentioned that the people who built these cathedrals didn't them of them as being "Gothic".

It should be mentioned that the people who built these cathedrals didn't them of them as being "Gothic".

That name was given by Renaissance scholars who disliked Medieval architecture and called it Gothic, in reference to the Goths who caused the fall of the Rome.

Such negative connotations have long since faded, of course, and Gothic architecture remains incredibly popular.

Such negative connotations have long since faded, of course, and Gothic architecture remains incredibly popular.

I've written about Gothic architecture before in my free newsletter, Areopagus.

It features seven short subjects every Friday, also including art, music, and history.

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, subscribe here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

It features seven short subjects every Friday, also including art, music, and history.

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, subscribe here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh