Navalny is a Russian opposition leader unjustly imprisoned on politically motivated charges. An eponymous documentary about him is one 2023 Oscar favorites. @navalny supporters are adamant that his history of racist and xenophobic positions is insignificant.🧵

They maintain that his views have evolved and that his far right nationalist persona is over a decade old and therefore irrelevant. I sympathize with Navalny’s struggle against Putin and believe that he should be freed. Yet, as a Central Asian, I find it hard to ignore his past.

I have seen Navalny supporters accuse anyone criticizing him of doing Putin’s bidding. But the truth is that people in places formerly colonized by Russia detest Putin AND are also weary of Navalny because of his well documented history as a far right Russian nationalist.

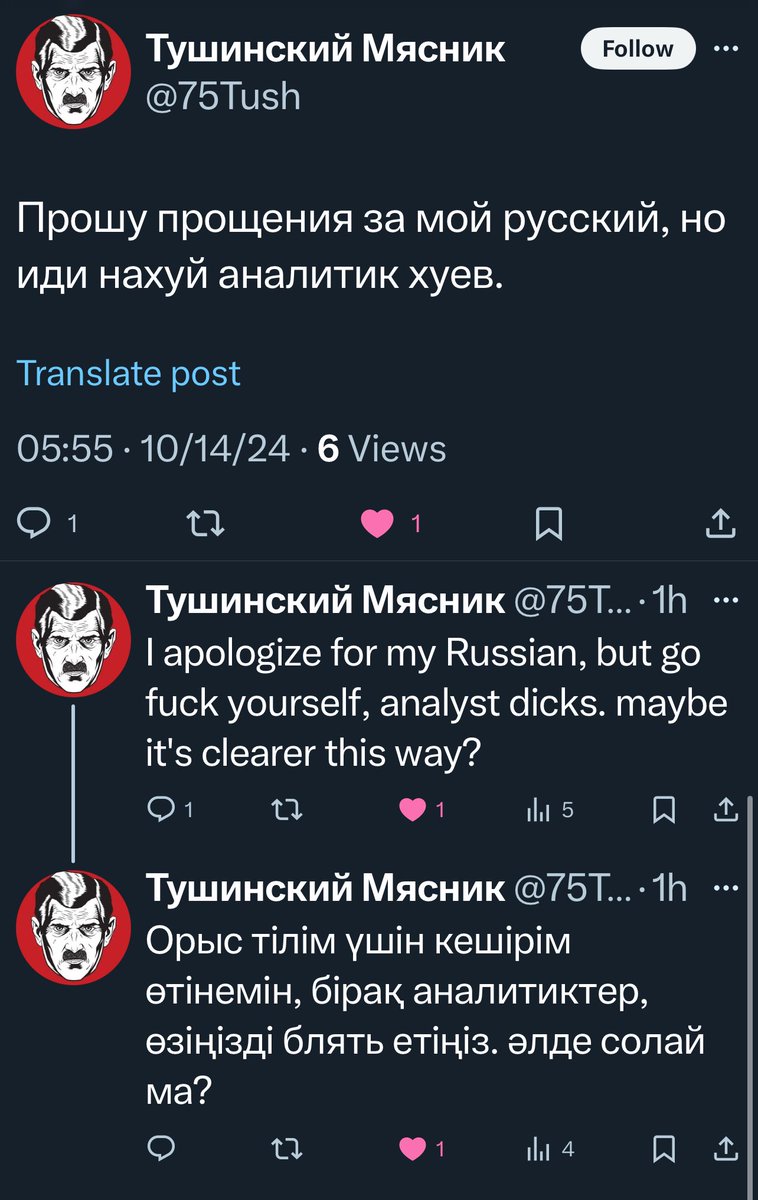

The unfailingly arrogant and dismissive tone adopted by Navalny’s closest associates like @pevchikh and @leonidvolkov as well as many other prominent “good Russians” does little to dispel these concerns among the formerly colonized.

Here’s an example of vintage Navalny. I suppose that stuff like this is easier to brush off as insignificant if you are NOT Central Asian. But I am Central Asian and, as much as I admire Navalny’s heroic struggle against Putin, I can’t shake the unease.

I couldn’t find a version with English subtitles so my own captions/translation are attached. Navalny’s opposition to Putin is real and he is paying a terrible price for it. But the largely two-dimensional view of Navalny as Russia’s savior is dangerously simplistic. THE END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh