The wacky history of glow-in-the-dark plants 🌱

A few years ago, "Glowing Plants" raised $484,000 on Kickstarter. Backlash followed and the platform banned gene-editing projects.

The original company died in 2017, but others took their place.

These are the highlights. 🧵

A few years ago, "Glowing Plants" raised $484,000 on Kickstarter. Backlash followed and the platform banned gene-editing projects.

The original company died in 2017, but others took their place.

These are the highlights. 🧵

Our story begins in molecular biology's golden era, 1986.

A small cadre of biologists & chemists at UCSD reported, in @ScienceMagazine, the "stable expression of the firefly luciferase gene in...transgenic plants."

The results were impressive.

science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

A small cadre of biologists & chemists at UCSD reported, in @ScienceMagazine, the "stable expression of the firefly luciferase gene in...transgenic plants."

The results were impressive.

science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

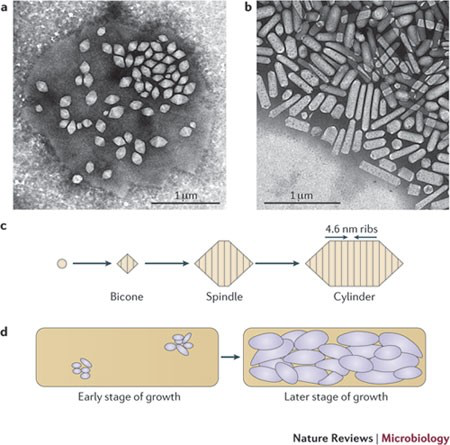

Decades later, in 2010, a group from Indiana University took up the spiritual torch of that initial project.

Specifically, they took all six genes from a firefly's lux operon, and ported them into tobacco plants.

The plants glowed, but...meh.

doi.org/10.1371/journa…

Specifically, they took all six genes from a firefly's lux operon, and ported them into tobacco plants.

The plants glowed, but...meh.

doi.org/10.1371/journa…

That same year, undergrads at the University of Cambridge continued the trend.

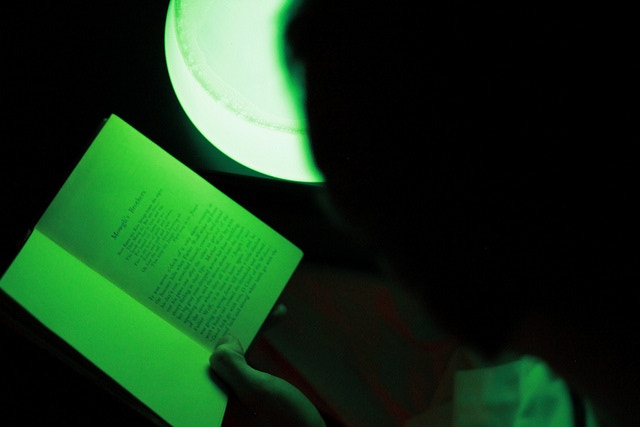

They put the firefly luciferase genes into bacteria & engineered the proteins to glow brighter; enough to read a book.

Was this an inflection point?

Were glow-in-the-dark plants ready for the home?

They put the firefly luciferase genes into bacteria & engineered the proteins to glow brighter; enough to read a book.

Was this an inflection point?

Were glow-in-the-dark plants ready for the home?

Antony Evans certainly thought so.

On 23 April 2013, he launched a project on Kickstarter. The goal: "Natural Lighting with no Electricity." The company, Glowing Plants, aimed to send Arabidopsis plants to those who pledged $40.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

On 23 April 2013, he launched a project on Kickstarter. The goal: "Natural Lighting with no Electricity." The company, Glowing Plants, aimed to send Arabidopsis plants to those who pledged $40.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

The team quickly reached $65k, their initial goal.

A "stretch goal" of $400k was reached in the following days.

Backers who pledged $150 or more would receive a glow-in-the-dark rose.

All of this work was a continuation, of sorts, of the 2010 projects.

2010.igem.org/Team:Cambridge

A "stretch goal" of $400k was reached in the following days.

Backers who pledged $150 or more would receive a glow-in-the-dark rose.

All of this work was a continuation, of sorts, of the 2010 projects.

2010.igem.org/Team:Cambridge

With lots of money comes lots of critics.

Drew Endy was skeptical about the science itself.

“Never mind the genetic engineering involved," he told @Nature. "Just what does the physics say about the feasibility of the project working out?”

nature.com/articles/49801…

Drew Endy was skeptical about the science itself.

“Never mind the genetic engineering involved," he told @Nature. "Just what does the physics say about the feasibility of the project working out?”

nature.com/articles/49801…

And he was right.

To make the plants glow, Glowing Plants would first have to insert SIX genes into Arabidopsis. Even then, there was no guarantee that the final plants would be bright.

"They never could get all six in at once," wrote @sarahzhang.

theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

To make the plants glow, Glowing Plants would first have to insert SIX genes into Arabidopsis. Even then, there was no guarantee that the final plants would be bright.

"They never could get all six in at once," wrote @sarahzhang.

theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

(Side note: In that photo, for @TheAtlantic, the company used long exposures to make the plant "appear brighter than it actually is.")

It has been a well-known problem, for decades, that plants with luciferase genes almost never glow super brightly.

That's why "glowing trees" haven't replaced streetlights along highways.

This article (at least, its headline) is literally bullshit. 🔻

newscientist.com/article/mg2082…

That's why "glowing trees" haven't replaced streetlights along highways.

This article (at least, its headline) is literally bullshit. 🔻

newscientist.com/article/mg2082…

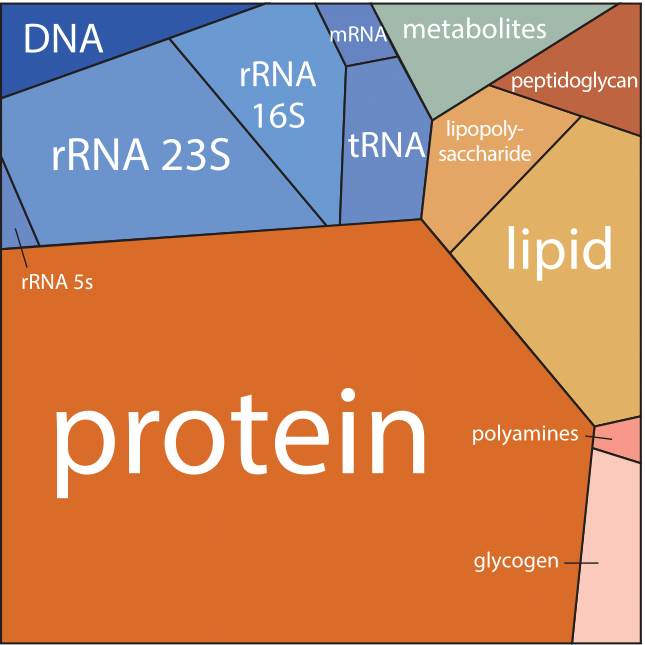

Engineering is always a battle of tradeoffs. This is true in biology.

The more light that a plant makes, the more energy that it consumes. This is called BURDEN.

Producing LOTS of light, without killing the plant, is an unsolved challenge.

arstechnica.com/science/2013/0…

The more light that a plant makes, the more energy that it consumes. This is called BURDEN.

Producing LOTS of light, without killing the plant, is an unsolved challenge.

arstechnica.com/science/2013/0…

Of course, burden (in a genetic context) mainly happens when LOTS of new genes are added to a cell.

Cells don't like the new genes because they require energy to upkeep. Energy is diverted from growth & metabolism.

@ProfTomEllis is the resident expert.

doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.…

Cells don't like the new genes because they require energy to upkeep. Energy is diverted from growth & metabolism.

@ProfTomEllis is the resident expert.

doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.…

But what if you didn't need genes to make a plant glow?

In 2021, Michael Strano at @MITChemE embedded nanoparticles inside of plant leaves.

"After 10 seconds of charging, plants glow brightly for several minutes." 10X brighter than other glowing plants!

news.mit.edu/2021/glowing-p…

In 2021, Michael Strano at @MITChemE embedded nanoparticles inside of plant leaves.

"After 10 seconds of charging, plants glow brightly for several minutes." 10X brighter than other glowing plants!

news.mit.edu/2021/glowing-p…

Anyway. Back on Kickstarter, shit was heating up.

In mid-2013, the platform changed their rules to block "creators of all future projects from handing out GMOs as rewards."

Their reason? Scientists are "unsettled" on the ethics of releasing GM organisms.

theverge.com/2013/8/7/45958…

In mid-2013, the platform changed their rules to block "creators of all future projects from handing out GMOs as rewards."

Their reason? Scientists are "unsettled" on the ethics of releasing GM organisms.

theverge.com/2013/8/7/45958…

Meh. Who cares. Kickstarter, shmickstarter.

Glowing Plants changed their name to Taxa Biotechnologies.

They raised another $310k on WeFunder.com.

They announced plans to make a "fragrant moss" and other engineered plants for the home.

wefunder.com/taxa/updates

Glowing Plants changed their name to Taxa Biotechnologies.

They raised another $310k on WeFunder.com.

They announced plans to make a "fragrant moss" and other engineered plants for the home.

wefunder.com/taxa/updates

For years — through 2017! — the founder posted regular updates on Kickstarter. 69 in total.

He talked about how fluorescent Arabidopsis were growing on the International Space Station.

He posted occasional technical updates...

He talked about how fluorescent Arabidopsis were growing on the International Space Station.

He posted occasional technical updates...

In August 2014, the company announced that they had been a part of Y Combinator, too.

But years later, in August 2016, only "5 out of 6 genes" had been "successfully integrated into a plant."

In April 2017, they stopped work on the project entirely.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

But years later, in August 2016, only "5 out of 6 genes" had been "successfully integrated into a plant."

In April 2017, they stopped work on the project entirely.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

In July 2017, the company still managed to ship their fragrant moss.

Glow-in-the-dark plants are hard. Nice-smelling moss, apparently, is much easier.

Alas, it wasn't enough. The company shut down in December 2017.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

Glow-in-the-dark plants are hard. Nice-smelling moss, apparently, is much easier.

Alas, it wasn't enough. The company shut down in December 2017.

kickstarter.com/projects/anton…

The company's founder, Antony Evans, went to work for Ryan Bethencourt's company, Wild Earth.

And when one company falls, many rise to take its place.

BioGlow. Light Bio. GlowPlant. All share a similar dream: Make glow-in-the-dark plants that are actually bright.

And when one company falls, many rise to take its place.

BioGlow. Light Bio. GlowPlant. All share a similar dream: Make glow-in-the-dark plants that are actually bright.

BioGlow has been around since 2010. They are the world's first glowing plants company (apparently).

They sell little bottles of glowing algae (which are cheap) and nutrients to feed the algae (which are expensive).

Shake the bottle & the algae glow.

bioglow.eu/shop/en/

They sell little bottles of glowing algae (which are cheap) and nutrients to feed the algae (which are expensive).

Shake the bottle & the algae glow.

bioglow.eu/shop/en/

GlowPlant has a super wide selection of glowing plants, too.

Bioluminescent bacteria. Bright, blue plants. Green fungi.

It costs just $20 for a small, glow-in-the-dark plant. That's pretty impressive.

glowplant.ca

Bioluminescent bacteria. Bright, blue plants. Green fungi.

It costs just $20 for a small, glow-in-the-dark plant. That's pretty impressive.

glowplant.ca

Perhaps the most serious company, though, is @light_bio.

They're also making "bioluminescent plants" for the home but, in April 2022, inked a deal with @Ginkgo to boost the brightness of their plants.

The genetic problem remains unsolved, it seems.

prnewswire.com/news-releases/…

They're also making "bioluminescent plants" for the home but, in April 2022, inked a deal with @Ginkgo to boost the brightness of their plants.

The genetic problem remains unsolved, it seems.

prnewswire.com/news-releases/…

So, why this obsession with glow-in-the-dark plants?

The market, historically, is small. These will only make it into every house when the plants are so bright that people say, "Holy shit, that's a bright plant."

Until then, I'd wager that every company is destined to nichedom.

The market, historically, is small. These will only make it into every house when the plants are so bright that people say, "Holy shit, that's a bright plant."

Until then, I'd wager that every company is destined to nichedom.

There are interesting applications for glowing plants in ag, though.

John Deere backed MIT-made plants, developed by @Inner_Plant, that glow when attacked by pests. Satellites detect problem plants, and alert farmers. The company raised a $16M Series A.

globalventuring.com/corporate/inne…

John Deere backed MIT-made plants, developed by @Inner_Plant, that glow when attacked by pests. Satellites detect problem plants, and alert farmers. The company raised a $16M Series A.

globalventuring.com/corporate/inne…

Other companies, like @neoplants, are using engineered houseplants to clean air.

For $179, they say their Golden Pothos recycles toxic, organic compounds "as effectively as 30 houseplants."

For $179, they say their Golden Pothos recycles toxic, organic compounds "as effectively as 30 houseplants."

https://twitter.com/NikoMcCarty/status/1615137843520868352

What we really need are 🌱 custom flowers 🌱.

Imagine that you could order a dozen roses with your partner's favorite colors. Or make sunflower with massive petals.

What if you could design a flower online, and have it shipped to your house? (h/t @ATinyGreenCell)

Beautiful.

Imagine that you could order a dozen roses with your partner's favorite colors. Or make sunflower with massive petals.

What if you could design a flower online, and have it shipped to your house? (h/t @ATinyGreenCell)

Beautiful.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh