Michelangelo was commissioned in 1501 to create a statue of David for Florence Cathedral.

Florence had recently become a republic again, and David was supposed to embody the spirit of the city, its democracy and values.

He was working for the city and the republic.

Florence had recently become a republic again, and David was supposed to embody the spirit of the city, its democracy and values.

He was working for the city and the republic.

While in 1917 Marcel Duchamp, then living in America, submitted his Fountain anonymously (under the name Richard Mutt) to the first exhibition of New York's Society of Independent Artists.

Unlike Michelangelo, Duchamp was just an individual artist making a provocative statement.

Unlike Michelangelo, Duchamp was just an individual artist making a provocative statement.

And so Duchamp's Fountain isn't, on its own merits, very interesting.

Much more compelling is the question of why Duchamp did it in the first place. And, once he did, why it was so influential.

Indeed, all modern conceptual art stems from Duchamp's infamous urinal.

Much more compelling is the question of why Duchamp did it in the first place. And, once he did, why it was so influential.

Indeed, all modern conceptual art stems from Duchamp's infamous urinal.

Part of the answer lies in one of Duchamp's earlier paintings: Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2, from 1912.

Taking plenty from Cubism and Futurism, two avant-garde art European art movements of the age, his inspiration for this painting was photography.

Taking plenty from Cubism and Futurism, two avant-garde art European art movements of the age, his inspiration for this painting was photography.

Just as AI has recently thrown up a host of new challenges for art, photography once did the same. Anybody with a camera could now do what once only artists could.

The French poet Charles Baudelaire had recognised photography as a potential threat to art way back in the 1860s:

The French poet Charles Baudelaire had recognised photography as a potential threat to art way back in the 1860s:

Duchamp was fascinated by it. His painting was inspired by the photographs of Étienne-Jules Marey, who had captured horses in motion over several superimposed frames.

Duchamp even experimented with photography himself, including his "Five Way Self Portrait".

Duchamp even experimented with photography himself, including his "Five Way Self Portrait".

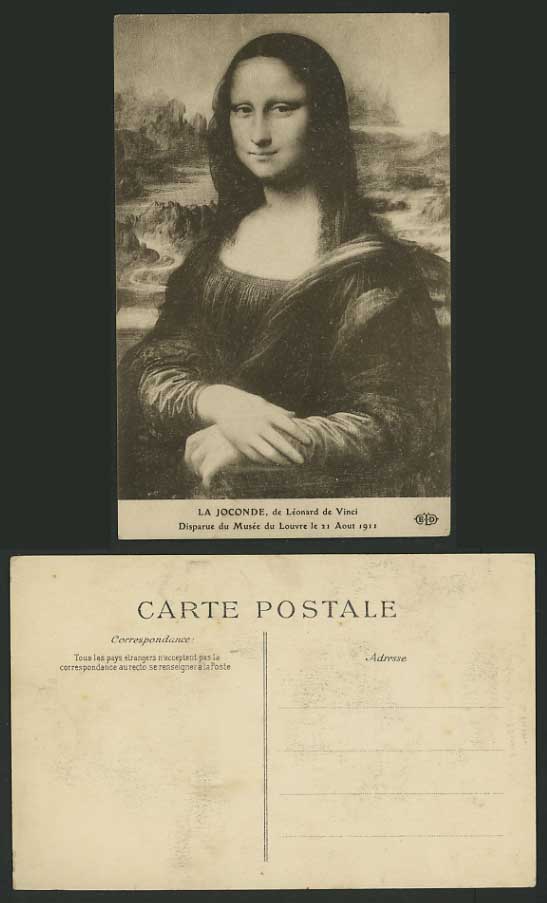

Another way photography impacted art, perhaps even more profoundly, is made clear in Duchamp's irreverant L.H.O.O.Q.

Prints of famous paintings had been around for centuries, but photography allowed the creation of highly accurate ones on a scale previously impossible.

Prints of famous paintings had been around for centuries, but photography allowed the creation of highly accurate ones on a scale previously impossible.

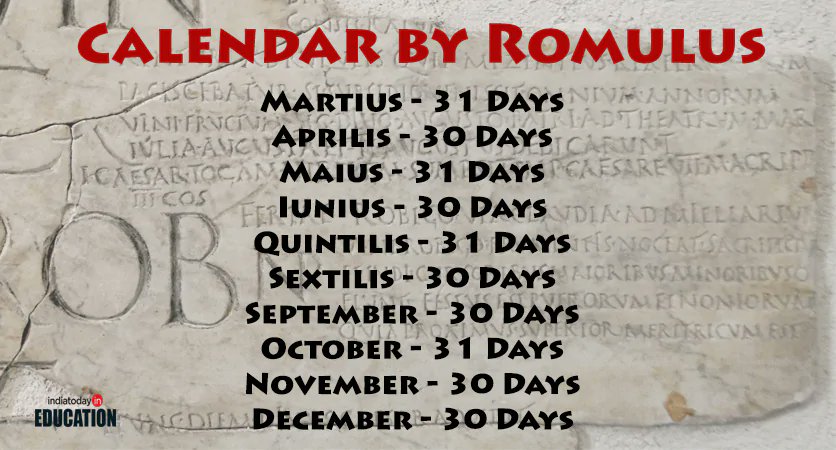

Suddenly *anybody* could own a print of the Mona Lisa, or of any famous painting. Art's once limited supply was now near infinite.

The old masterpieces were everywhere - even on postcards - so why make new ones?

L.H.O.O.Q. seems like a bitter mockery of that fact.

The old masterpieces were everywhere - even on postcards - so why make new ones?

L.H.O.O.Q. seems like a bitter mockery of that fact.

The Fountain itself was one of the "readymade" artworks created by Duchamp, where he took everyday objects and simply called them art.

He wanted to turn art from an aesthetic craft into an intellectual process. In his words this was about appealling to the mind, not the eye.

He wanted to turn art from an aesthetic craft into an intellectual process. In his words this was about appealling to the mind, not the eye.

But it was industrial mass-production as much as photography that destabilised the world of art.

What were once artisinal objects that only a few craftspeople could create were now everyday items, available in department stores for anybody to buy and take home.

What were once artisinal objects that only a few craftspeople could create were now everyday items, available in department stores for anybody to buy and take home.

And so when people very fairly point out that Duchamp's Fountain (and much modern art that has followed it) required no skill... they're right, and that was the point.

The skills of individual artists had been swallowed up by the possibilites of industrial manufacturing.

The skills of individual artists had been swallowed up by the possibilites of industrial manufacturing.

Rather than skill it was intellectual daring that would, in Duchamp's mind, define the modern artist.

The public already had their masterpieces - so what else did the artist, no longer needed, owe them?

That, at least, was one line of reasoning.

The public already had their masterpieces - so what else did the artist, no longer needed, owe them?

That, at least, was one line of reasoning.

Marcel Duchamp, like many of his contemporaries, was simply posing the question that had already been asked (and answered) by technology.

What was the role of artist in modern society? They had been challenged and perhaps even displaced.

Readymade art was a way of responding.

What was the role of artist in modern society? They had been challenged and perhaps even displaced.

Readymade art was a way of responding.

But related to all this was something happening on the other side of the Atlantic. While Duchamp was presenting his purely intellectual art in New York a war was ravaging his homeland - France - and the rest of Europe.

Nothing would ever be the same again.

Nothing would ever be the same again.

The First World War was, for many people, a complete betrayal - the world they had been brought up to believe in, its art and values and culture, had led to a conflict of unimaginable violence and desolation.

Artists, like so many, turned away from the past.

Artists, like so many, turned away from the past.

Duchamp himself soon becamely involved with the fiercely anti-establishment Dadaist movement in Europe, which was a direct response to the First World War.

They rejected their society - its logic, its values, and its aesthetics - and adopted Duchamp's self-proclaimed "anti-art".

They rejected their society - its logic, its values, and its aesthetics - and adopted Duchamp's self-proclaimed "anti-art".

But, looking beyond their words, the art of a key Dadaist member like Man Ray gives us some idea of what interested - and frightened - them.

His drawings were more like industrial diagrams; technology was fundamentally changing the world.

His drawings were more like industrial diagrams; technology was fundamentally changing the world.

Is The Fountain art? Duchamp said it was anti-art, and yet he presented it at an artistic exhibition.

Perhaps such intellectual jokes doesn't matter at all.

What really matters is that the Fountain speaks to its age - art is always a barometer for society.

Perhaps such intellectual jokes doesn't matter at all.

What really matters is that the Fountain speaks to its age - art is always a barometer for society.

Michelangelo's David represents something fundamental about Florence in the early 1500s.

And Duchamp's Fountain says much about the early 20th century, reeling from the social, political, economic, and cultural consequences of rapid technological progress and all out war.

And Duchamp's Fountain says much about the early 20th century, reeling from the social, political, economic, and cultural consequences of rapid technological progress and all out war.

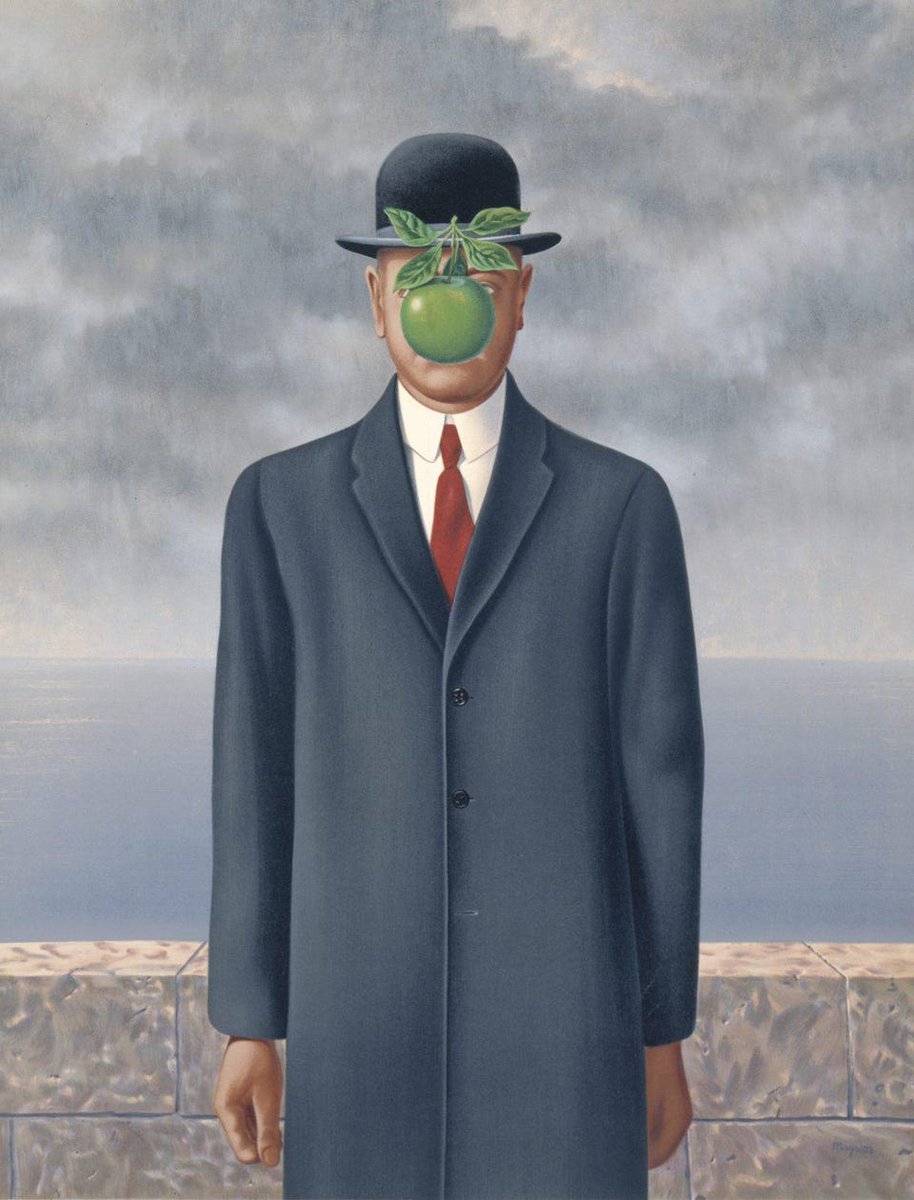

None of this means the Fountain is an inevitable conclusion - not everybody reacted to all of this in the same way.

The Surrealists, for example, were also a direct response to the First World War. But they continued to paint with the methods of traditional art.

The Surrealists, for example, were also a direct response to the First World War. But they continued to paint with the methods of traditional art.

And, by a strange twist of fate, Auguste Rodin died in the same year that Duchamp presented his Fountain.

Rodin, regarded as one of the greatest artists of his age, was still working on the Gates of Hell at the time of his death, and the Thinker was barely a decade old.

Rodin, regarded as one of the greatest artists of his age, was still working on the Gates of Hell at the time of his death, and the Thinker was barely a decade old.

Duchamp's Fountain has been controversial ever since its creation, and that reputation is sure to endure.

Is it a great work of art? Is it even art? Well, it can hardly be compared to Michelangelo's David.

But, as a sign of the times, it does what only art can do.

Is it a great work of art? Is it even art? Well, it can hardly be compared to Michelangelo's David.

But, as a sign of the times, it does what only art can do.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh