Is what UK farmers now face similar to what UK coal miners faced back in the 1980s? Some inexpert thoughts.

🧵

🧵

In the 80s coal mining was subsidised to the tune of £1 billion a year in 1980, or in today's money, about £5 billion. Not so different to the ~£3.3 billion received by farmers just a few years ago.

api.parliament.uk/historic-hansa…

api.parliament.uk/historic-hansa…

Without those subsidies a great number of pits and farms would fail to break even.

assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl…

assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl…

In the 80s the British Coal Board wanted to close uneconomic pits. This paper discusses the question of what is an uneconomic pit. Is it the threshold where the marginal pit is losing so much money that this industry as a whole does not break even?

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.111…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.111…

Or is it the threshold at which the marginal pit itself does not reach breakeven point?

By comparison, for farming we have these splits:

By comparison, for farming we have these splits:

This slicing up until now hasn't been so obvious in the post Brexit farming discussions, but we're beginning to see a bit of it now:

https://twitter.com/herdyshepherd1/status/1620866544501919744

As with pit closures and discussion around job losses, there has been much talk about a radical overhaul of farming & land use change, but much less discussion about the right or the optimal level of farms that should not continue production.

The NFU feels a bit like the National Union of Mineworkers: no reduction in food production except on geological grounds. Indeed, they even seem opposed to it even on geological grounds to the point that the Solar Panel Research Group is surely near. They channel Lord Shinwell.

Today the NFU thinks food production is more important than energy production. Back in the day coal production was for some more important than food production. Everyone has their own Most Important Thing.

api.parliament.uk/historic-hansa…

api.parliament.uk/historic-hansa…

In comparison, the question then as it is now is just how much do we need food / coal production? History tells us that the answer to coal was that we managed without. Other sources of energy came along.

ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy…

ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy…

What about food? The alarm bells being rung by the NFU is that we cannot afford to reduce food security in the UK, and so we cannot afford to allow food production to fall one bit. Produce less beef, import more from polluting foreign sources, they say.

However, what they left unsaid is that, like energy, there are different forms of food, and different foods require different amounts of stuff to produce them.

And now we bring in climate change the biggest difference between the debate in the 1980s and now.

And now we bring in climate change the biggest difference between the debate in the 1980s and now.

Those defending pit closures in the 80s didn't have the spectre of climate change to contend with. Farming has challenging economics in a challenging climate.

So you would think the NFU would be against climate change and its threat to farming and food production?

So you would think the NFU would be against climate change and its threat to farming and food production?

Well, nope. In fact, the NFU proudly committed UK farmers – not that many of them feel like the NFU ever asked them – to net zero in 2040. A full ten years ahead of the most ambitious timelines anyone else was thinking about. Strategic genius, right?

Well, yes, if like the NFU you think we can generate 26 MtCO2e of saving using bio-char, bioenergy with CCS and bio-based materials industry without any change in consumer behaviour. However, if like the Committee on Climate Change, you think these "more speculative", maybe not.

The big problem for the NFU is that, absent bio-char revolutions, according to the Committee on Climate Change's Land Use document, the most impactful way to achieve the goal of net zero is to use land for things other than food production.

In particular, 20% reduction in consumption of high carbon intensity foods like beef, lamb and dairy – meaning 10% reduction in cattle & sheep numbers – freeing up land to plant 30,000ha of new forest every year.

Put another way, have the NFU patted themselves on the back for putting quite a lot of sheep, dairy and beef farmers out of business 10 years earlier than would otherwise have been the case?

#owngoal

#owngoal

Many farmers have advanced many arguments about why current UK farming need not be sacrificed on the altar of net zero. They complain about those taking plane flights and decry that they are not listened to by policy makers.

My biggest worry here is not that they have not been listened to (and, by implication, if they were heard, everyone would be persuaded), but rather these arguments have been heard, and they have not really moved the dial. A few examples to follow.

Common refrain I hear is GWP100 vs GWP* as a measure of ruminant methane emissions, given the cyclical and shorter lived nature of methane, the livestock problem becomes a lot less. The CCC report hears this, but ultimately disregards it.

pp 42-46: theccc.org.uk/publication/la…

pp 42-46: theccc.org.uk/publication/la…

Another is that agriculture is being blamed whereas it should be seen as the saviour due to its carbon sequestration potential in soils. This features heavily in the NFU 2040 document. CCC unimpressed though, rightly or wrongly (for minerals soils at least).

They go on to talk a bit more about grazing practices here, again saying it is not a panacea (again, rightly or wrongly).

Some argue that why should farmers do anything. It should be the people on planes, in China, driving to work, breathing too heavily etc who should clean up their act first. Tu quoque essentially. Again, CCC not impressed.

Another is around carbon leakage. Produce less at home and we end up cutting down the rainforest to produce meat. Again, argument heard, particularly on bad trade deals, but ultimately with a 20% reduction in per capita consumption of beef & lamb, not necessarily a problem...

So what is this all to say? It is to say despite lots of points being made by farmers, I am not very confident they are winning the argument in the corridors of power.

This means that civil servants who read this sort of land use document will, I think, conclude that a managed decline in livestock numbers is unavoidable to meet the policy goals.

(Worth noting that diet change and land use change results in a 9% decline in beef cattle numbers for example, but even GWP* advocates need a 10% decline.)

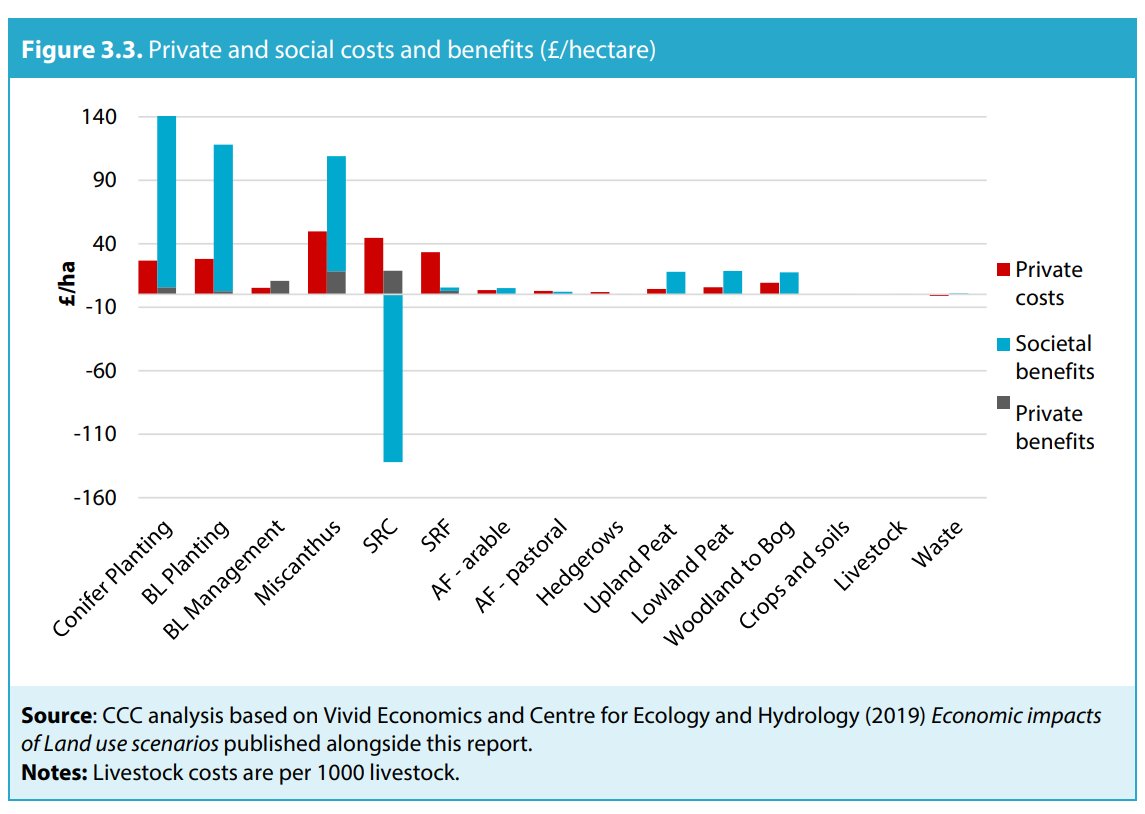

And the further problem I think for farmers is that according to the cost benefit analyses, their managed decline allowing tree planting is pretty much the highest return option by some way.

I was listening to the oracle that is Janet Hughes the other day and on the call was a sheep farmer from Cumbria. For him, the new ELM schemes are simply not paying his bills with BPS disappearing & all around him hedge funds (tree funds?) are buying up land and planting trees.

The problem from DEFRA's perspective, if they are acting on received wisdom in elite policy circles, is this is at least approximately what their documents will be telling them is the right thing to happen.

So whilst they might be sympathetic, are they about to hike ELM rates to support the sort of activity that they think they need to reduce? I'm not confident.

And so I come back to coal: What are the similarities?

And so I come back to coal: What are the similarities?

It would seem both situations have a large part of an industry that does not make money without the need of government support. We have had, as is pointed out below, governments in both cases with a free market ideologies.

https://twitter.com/JoeWStanley/status/1621395976001912839

Both in a period of high inflation, with government finances being stretched & demands for rectitude in government expenditure. And for coal miners and farmers, people who take huge pride in their work and their way of life, but without necessarily other local jobs to go to.

I fear we sit at the brink of the erosion, even if it takes a decade or two, of large swathes of farming culture and landscape. There will be no announcements of farm closures like with the pits. People and businesses will just sink beneath the surface.

fwi.co.uk/news/farm-poli…

fwi.co.uk/news/farm-poli…

And so those are the similarities with coal. What about the differences? Ultimately the coal industry still lost and its decline hastened post the 80s despite the most obvious difference between then and now: the coal miners were prepared to stand together and fight.

Above I compared the NFU & NUM's arguments against closures, but there the similarity ends. Whereas the latter were decidedly militant, the NFU consider a photo taken with a minister and promise of sunlit uplands as an excuse to go home for tea pleased at a mission accomplished.

And farmers themselves seem, at present, still far away from anything resembling the Dutch farmers or the miners level of disruption and protest. But I think this piece by @Merry_Meredith is accurate, discontentment is brewing.

fwi.co.uk/news/editors-v….

fwi.co.uk/news/editors-v….

Anger at Red Tractor and its failure to deliver any form of premium for the red tape it creates. Anger at the NFU. But is there willingness to cease production, to incur extreme hardship, for farmers in a different part of the country whose livelihoods are threatened?

The images at the beginning of this news piece are powerful. Striking miners willing to comb beaches for fragments of coal to heat their homes, rather than return to work and break the strike.

Can you imagine a news piece showing a farmer foraging the hedgerow for berries because they cannot afford to buy food as a result of ceasing production on their farms as a protest against against government policy?

Without the Dutch equivalent or mining equivalent or government announcing or forcing the closure of farms to act as a catalyst for an eruption of sentiment, is the most likely scenario, with the slow reduction in direct payments, just businesses slowly dying in silence?

I think back to this paper about how NZ farmers coped after their radical reform episode in the mid 80s. It seems that a lot suffered extreme hardship, without barely a whimper to the outside world.

https://twitter.com/JRDSills/status/1597952079800041472

@threadreaderapp, please unroll.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh