The world of football stadiums is filled with history, character, charm, and some incredible architecture.

Many of them are instantly recognisable or have unique features - like the tower and neoclassical colonnade of the Stadio Renato Dall'Ara in Bologna.

Many of them are instantly recognisable or have unique features - like the tower and neoclassical colonnade of the Stadio Renato Dall'Ara in Bologna.

Or the Estadio Alberto J. Armando in Buenos Aires, better known as La Bombonera, meaning "Chocolate Box" in reference to its unusual shape and single flat stand.

And then there's El Monumental in Lima, with those striking tiers of viewing boxes above the regular stands.

Sometimes it's a particular feature which stands out, like the twin towers of Old Wembley in London (now demolished), the deep moat of the Stadio Diego Maradona in Naples, or the decorative facades of Highbury (now demolished) in London and Villa Park in Birmingham.

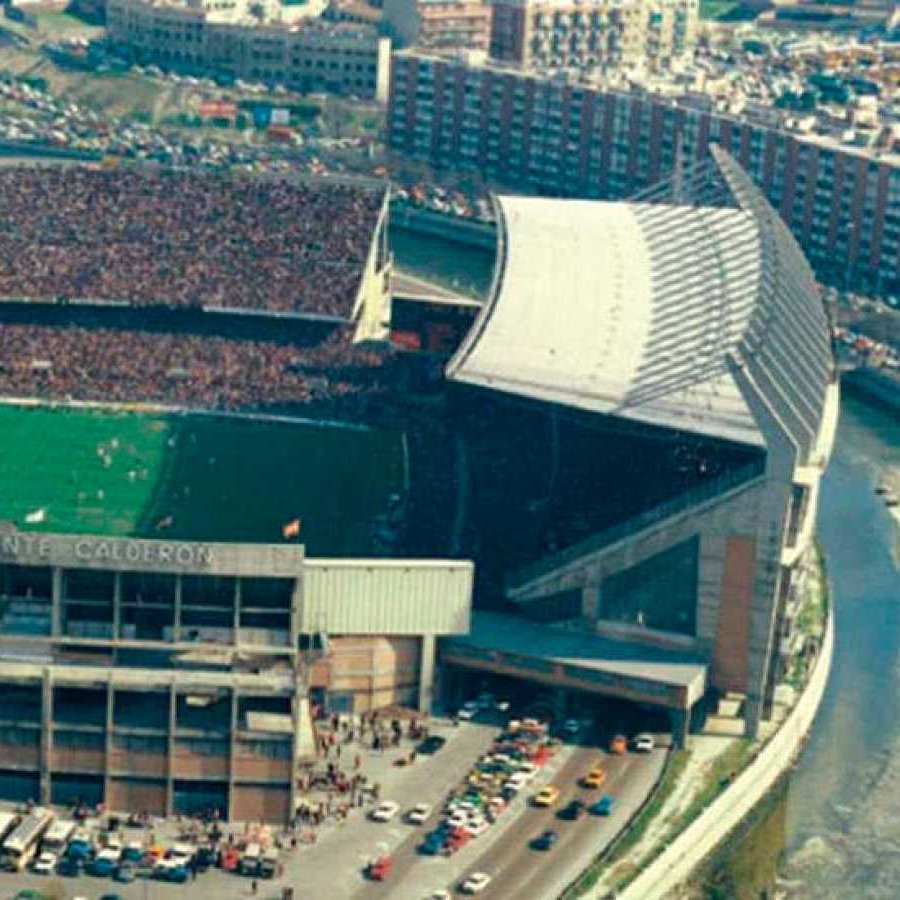

It could even be a shadow, like the famous "spider" on the pitch at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, or the road that ran beneath Atlético Madrid's former stadium, the Vicente Calderón.

Every old stadium seemed to have its own idiosyncracies.

Every old stadium seemed to have its own idiosyncracies.

Then there's something like the Allianz Arena in Munich.

Though similar to many other modern stadiums in some ways, its exterior - which can light up in a variety of colours - makes it something special.

Though similar to many other modern stadiums in some ways, its exterior - which can light up in a variety of colours - makes it something special.

The list of instantly recognisable football stadiums could go on.

But, as old stadiums are renovated and new ones are built all around the world, it can feel like those unique characteristics are disappearing and they are becoming much more similar, even indistinguishable.

But, as old stadiums are renovated and new ones are built all around the world, it can feel like those unique characteristics are disappearing and they are becoming much more similar, even indistinguishable.

But stadiums have looked the same for most of history; it's just that trends were national or regional rather than global.

Like the grounds of northern Europe with their low roofs, boxy geometry, and (usually) separated stands.

Like the grounds of northern Europe with their low roofs, boxy geometry, and (usually) separated stands.

Or in southern Europe, where the weather is better, stadiums with connected stands and a roof over only one side.

It's in the last twenty years that this has started to change.

As money has poured into football like never before, a whole new era of stadium-building has dawned, one in which the increasingly global game has seen homogenising architectural trends, dominated by the same firms.

As money has poured into football like never before, a whole new era of stadium-building has dawned, one in which the increasingly global game has seen homogenising architectural trends, dominated by the same firms.

It was inevitable that the old stadiums, built from crumbling concrete and rusting girders, would be replaced.

Some of the earliest truly modern stadiums were the Estádio da Luz in Lisbon and the Emirates Stadium in London, built in 2003 and 2006 by the same architectural firm.

Some of the earliest truly modern stadiums were the Estádio da Luz in Lisbon and the Emirates Stadium in London, built in 2003 and 2006 by the same architectural firm.

They were both trend-setters, not least because they represented the first step towards a global style.

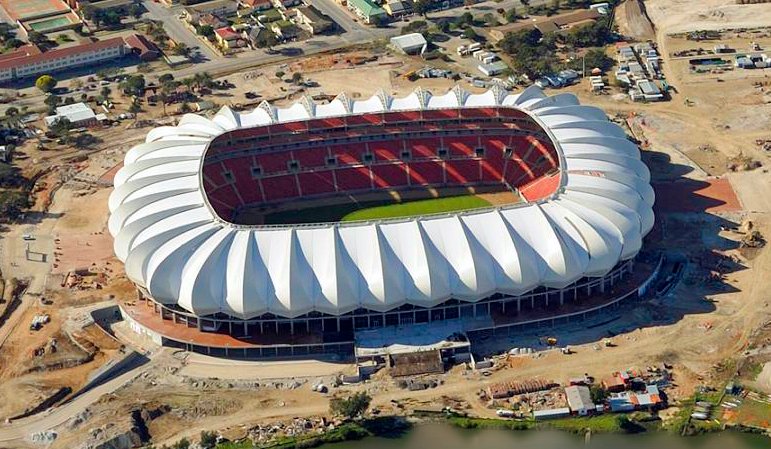

And international fashion has continued to dominate - here are four stadiums from the last four World Cups, which took place in South Africa, Brazil, Russia, and Qatar.

And international fashion has continued to dominate - here are four stadiums from the last four World Cups, which took place in South Africa, Brazil, Russia, and Qatar.

Of course, renovations and new stadiums are important. Income from ticket sales is vital and better facilities for players, staff, fans, and broadcasters are only a good thing.

And many old stadiums, however great their charm and history, are falling to pieces.

And many old stadiums, however great their charm and history, are falling to pieces.

But it seems as though something is being lost in this process, whereby the world's many recognisable stadiums are fading into a crowd of standard global models.

Barcelona's Camp Nou, famous for its asymmetrical shape, is soon to be renovated in keeping with the current fashion.

Barcelona's Camp Nou, famous for its asymmetrical shape, is soon to be renovated in keeping with the current fashion.

And the legendary San Siro in Milan has been singled out for demolition.

Set to be replaced with a stadium designed by the same firm behind the Estadio da Luz, the Emirates Stadium, and the new Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

Set to be replaced with a stadium designed by the same firm behind the Estadio da Luz, the Emirates Stadium, and the new Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

Not all new stadiums look the same, of course, but it's clear is that a new era has arrived, one in which global rather than local trends dominate.

And, despite their benefits, these high-tech stadiums have relinquished some of the charm and character of their predecessors.

And, despite their benefits, these high-tech stadiums have relinquished some of the charm and character of their predecessors.

Then again, every old stadium was once brand new, and people must have thought the same things about them.

Like the San Siro, seen here in 1956 before many of its current features were added.

All these new stadiums will one day be demolished - and probably missed, too.

Like the San Siro, seen here in 1956 before many of its current features were added.

All these new stadiums will one day be demolished - and probably missed, too.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh