Continuation of this thread below ⬇️

Part II: The term "Turk" in the Classical Ottoman era

Part II: The term "Turk" in the Classical Ottoman era

https://twitter.com/FranseviEfendi/status/1623086202457931778

In the Ottoman documentation, the word “Turk” isn’t used to refer to the Empire nor to their Muslim subjects before the 19th C.⬇️

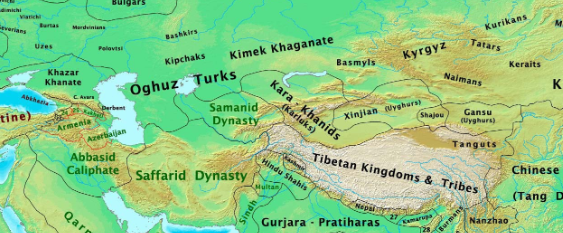

During the first centuries of the Empire, “Turk” (declined as an Arabic word: sng. “Türk”> pl. “Etrâk”) refers to country folks, either nomadic or sedentary. ⬇️

And here we get the derogatory terms used in the Ottoman literature such as “ اتراك بیادراك / Etrâk-i bî-idrâk” (unintelligent Turks), “اتراکك وجود ناپاکی / Etrâkin vücûd-ı nâ-pâki” (the impure body of the Turks), “ترك بدلقاء / Türk-i bed-likâ’” (ugly faced Turks), etc ; ⬇️

that is so often cherrypicked by people with no understanding of the context to denounce the so-called “anti-Turk behaviour” of the Ottomans which is itself a self-contradictory affirmation⬇️

These kinds of derogatory terms were not exclusive to what Ottoman administration identified as Turks but were also used against any other rural groups such as Kurds, Arabs and Tziganes.⬇️

What should be denoted here is not some kind of “anti-Turk” behaviour of the Ottoman elites which would be a completely anachronistic behaviour as their identification factor was not based our modern concept of the ethnicity/nationality ⬇️

but classical disdainful stance for a dominant and educated class for rural folks and lower classes. In the same era a nobleman would behave no different towards peasants of his own country.⬇️

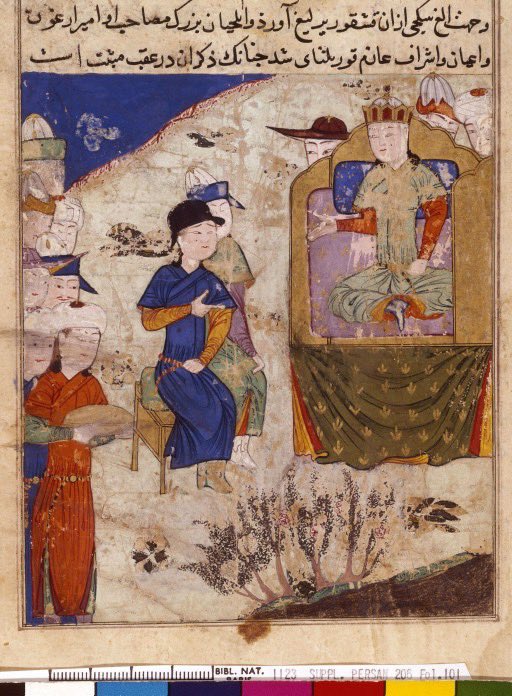

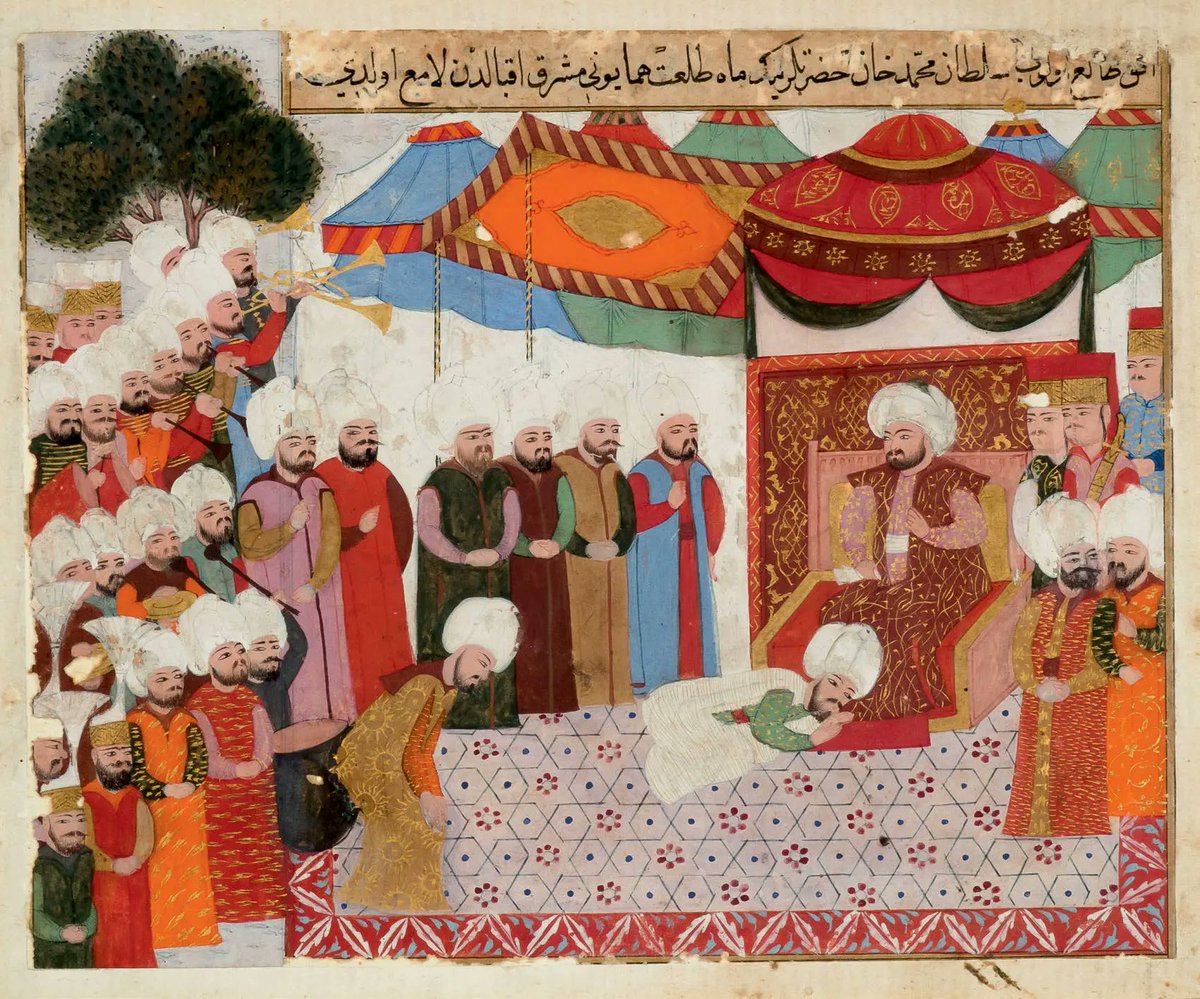

“Turk” wasn’t only synonymous of negative meaning in the mouth of the Ottoman elites. The valour of Turks was also praised and the young boys recruited via the devshirme were entrusted to rural Turks in order to roughen them.⬇️

Thus, for the Ottoman elites, the Turk is a boorish countryman whose military valour is much appreciated.⬇️

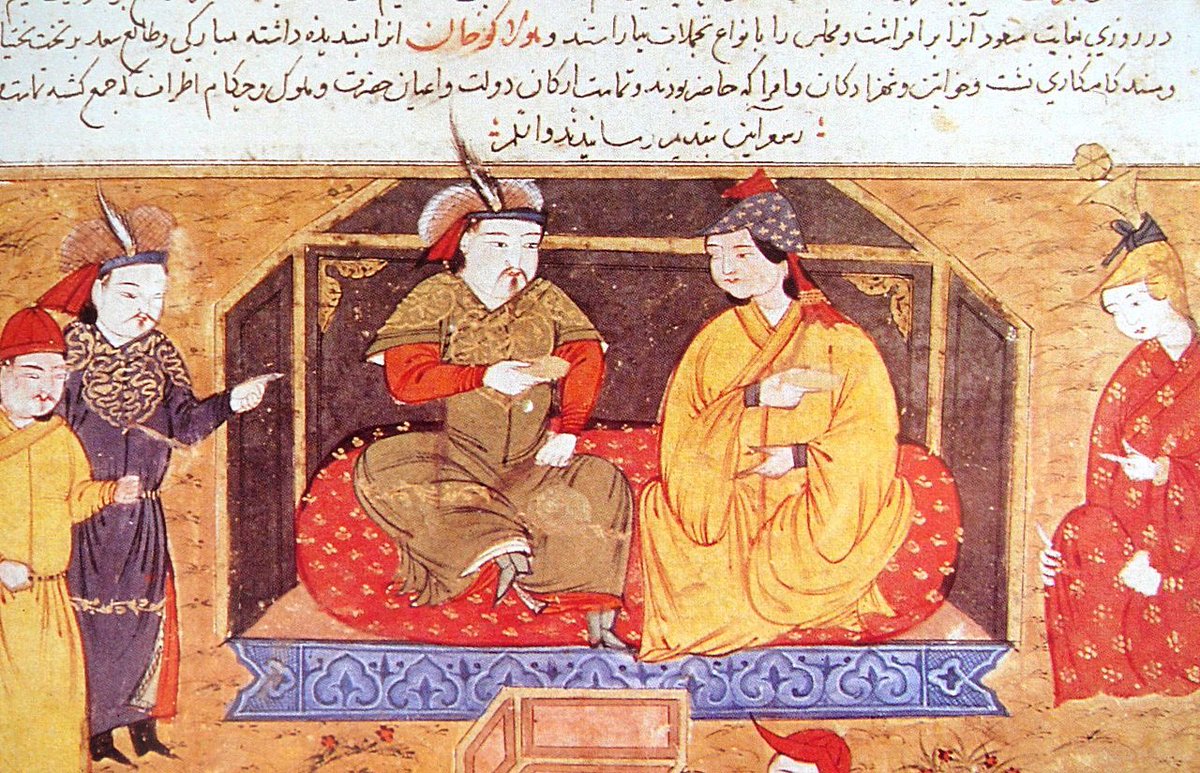

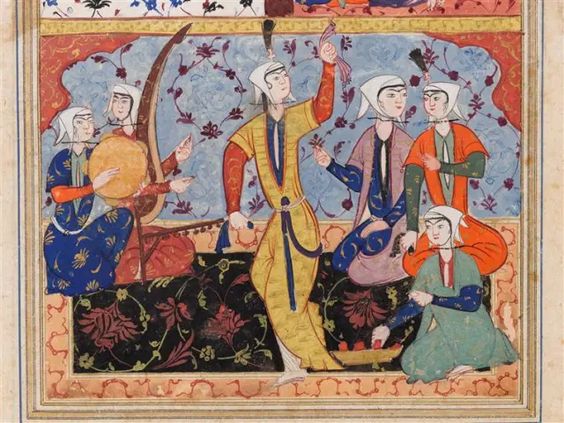

Another image of the Turk in Ottoman literature is its association with beauty. An aspect also well known in Persian literature as Rûzbihân Baqlî in his description the angels surrounding God says that “they’re like pretty girls beautiful as young Turks” ⬇️

or Later Hafez would say in a very popular distich that he would give Samarkand and Bukhara “for the mole on the cheek of this Turk from Shirâz”.⬇️

To sum it up, as we’ve seen the Ottomans inherited the pretty complex conceptions from the Middle Ages and their vision of national identity was nowhere similar to our modern one.⬇️

The dynasty and the elites of the capital and central provinces didn’t identify themselves as “Turkish” but, as it was the case in other Eastern realms of the same era, they rather referred to themselves according to the ruling dynasty and thus as “Ottomans”.⬇️

The word “Rûm” which referred to a cultural area (Balkans and Anatolia) as well as to its population was also widely used by the Ottomans (and not only the high classes). Despite deriving from Ῥωμαῖοι (Rhomaioi, Greek for Roman),⬇️

the use of such an autonym by the Ottomans nowhere proves their identification to the romano-byzantine heritage but rather their consciousness of living in the lands once ruled by Byzantium⬇️

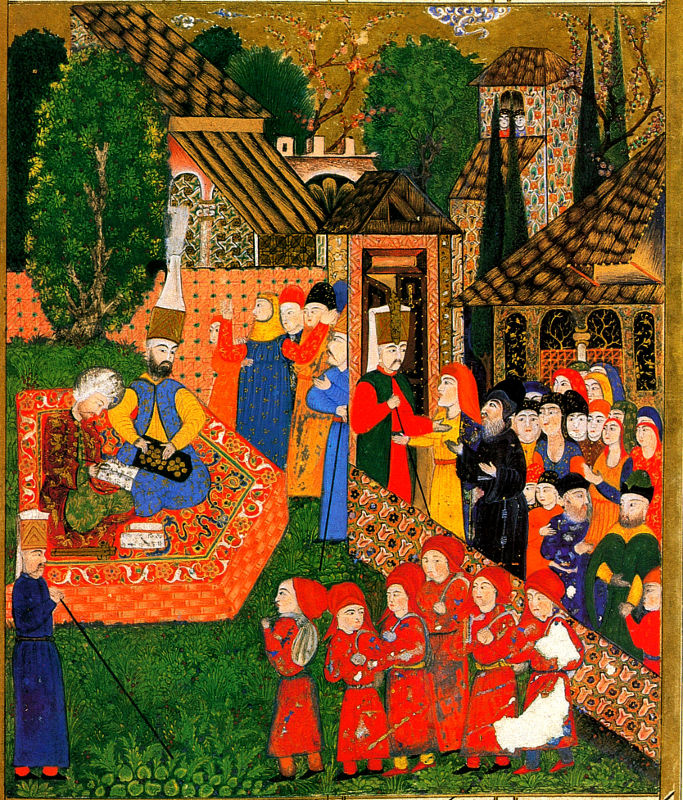

On the state’s level, where Westerners often referred to the Ottoman Empire as the Turkish Empire, Ottomans who were the spearhead of Islam as the holder of the caliphal title and also ignored the notion of Empire rather referred to their state as :

"Devlet-i Aliye" (the Sublime State) often attaching the name of the dynasty دولت علیه عثمانیه (Devlet-i Aliye-i Osmâniye) and referred to their territories as ممالك محروسه (Memâlik-i Mahrûse, the Well Protected Country).⬇️

But while in central provinces, Turk was synonymous of a countryman and thus the elites avoided to refer to themselves as Turks, in the Arab provinces, where Turks where a minority, the Ottoman elites were proud to refer to themselves as Turks⬇️

as this allowed them to differ from the commoners and put the emphasis on their bonds with the government of Constantinople. And here we note a very basic human reaction, the attempt from a ruling class to differ from the common.⬇️

In provinces where Turks are the majority it's normal for the elites to try to distinguish themselves from the plebe and thus avoid to identify themselves as Turks. But where Turks are a ruling minority they can fully embrace their Turkishness as it becomes a mark of nobility...

End of the Part II

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh