A thread on Black soldiers in 18th century European armies. Later this year, @ChevalierMovie is going to tell the story of French Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Black men fought (in small numbers) in most armies, we'll focus on the Russian, Prussian, British and Hessian forces. 1/25

I've been passionate about sharing this history for sometime, and presented at the @ConsortiumRev on this topic in 2022. The post does contain some offensive language in period quotations, I've replaced original language where possible. 2/25

Writing the history of enslaved people requires a great deal of care. I hope this thread respectfully explores some of the complexities of the service of these men, who both suffered a lack of freedom, and were able to use their service to improve their social status. 3/25

These Black soldiers had a wide range of experiences: as human beings, they were given as gifts, were the object of stares on the part of Europeans who had previously not encountered Africans, could earn higher wages than white soldiers, some even acquired powerful patrons. 4/25

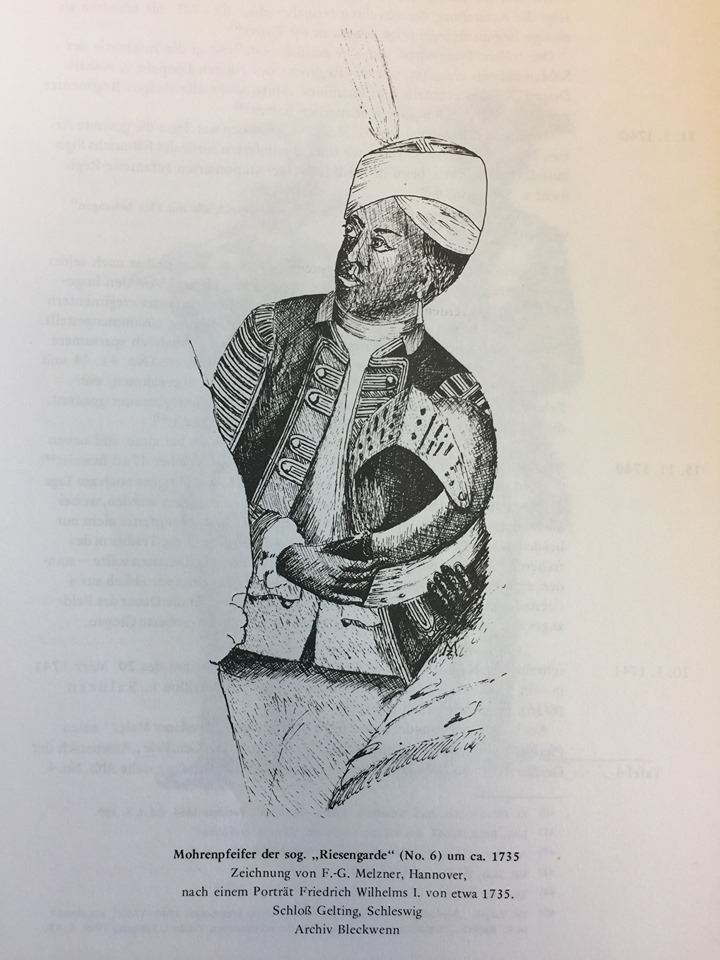

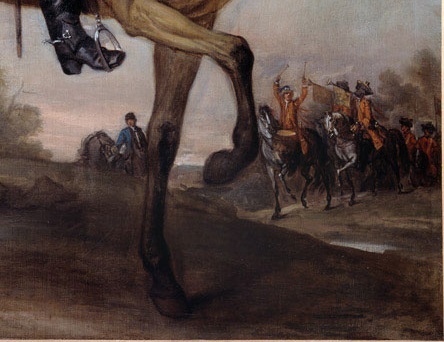

Most European armies included a few black soldiers, who were often employed as musicians, particularly as drummers and fifers. A few of these men also served as laborers, and there is evidence to suggest that in some armies, small numbers were employed in combat roles. 5/25

Many were purchased in Africa or North America for inclusion as symbols of prestige. The use of these men, particularly their uniforms, was a part of a larger process of emulating the fashion of the Ottoman Empire, a craze which swept through Europe during this period. 6/25

Being men were purchased, and thus experienced part of the painful world of slavery. They drew a wage. Particularly in the Prussian service, data from 1747 indicates that black musicians were paid 4 Thalers per month, double the wage of white musketeers. 7/25

Where records are available, it appears these men were discharged and free at the end of their service. Some men used the desire for "exotic" bands on the part of European officers for their own ends: joining European militaries to escape from the world of enslavement. 8/25

Though the Russian court imported an Ottoman military band in 1725, there are few images of African soldiers serving as musicians in the Russian Army. However, a number of Africans found their way into Russian service as well. The most famous of these is Abram Gannibal. 9/25

Gannibal was brought as an enslaved person to Istanbul, and sent to Russian as a gift to Tsar Peter I in 1704. With this adoption and patronage, Gannibal traveled to France to learn modern military science, and he briefly served in the French Army. 10/25

He was exiled to Siberia at upon Peter's death, but with the succession of Elizabeth Petrovna to the throne in 1741, Gannibal returned to power, was promoted to Major General, and briefly became the governor of Estonia. 11/25

With power came privilegez: he became the owner of several estates, and as a result, owned many families of serfs and profited from their labor. Abram’s most famous descendant is Alexander Puskin, but his son Ivan was heavily involved in the Russian conquest of Ukraine. 12/25

In Prussia the history of African soldier-musicians goes back to seventeenth century, when in 1685, Frederick William, the Elector of Brandenburg, brought a drummer, whose European name was Ludwig Besemann, into his army. 13/25

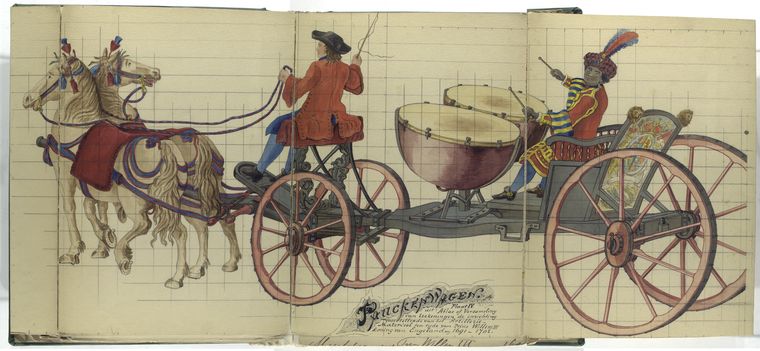

It appears that Frederick William I and Frederick II ("the Great") of Prussia maintained a Paukenwagen or a mobile drum platform, for their artillery. You can see a Dutch example of this type of carriage from the era of William III below. 14/25

However, Ottoman emissaries were not impressed by Frederick II's efforts to imitate their bands. After a presentation of a military band, Ottoman Ambassador Achmed Effendi shook his head, and simply commented to the Prussian king, "It is not Turkish." 15/25

Despite African soldiers relatively frequent service as musicians in Europeans armies, they still faced surprise from local people. Ensign Hugh Mackay of the 13th Regiment of Foot described the surprise of townspeople in the Netherlands at seeing African musicians: 16/25

"At 3 O'Clock....Riches Dragoons-- enter'd the Town with their black Drummers- at whom the people stared like bewitched, wondering to see Blacks amongst the English Soldiers." This quote gives a window into the sort of reactions which black troops faced. 17/25

Like other European armies, the British regular army acquired black soldiers through the purchase of human beings. The diary of John Peebles on March 4th 1780 indicates: "picked up a little [black child] for a fifer." 18/25

The practice of utilizing black musicians followed armies to North America. In June of 1781, Hesse-Hanauer Captain Georg Pausch reported to his Landgraf that, "The Hesse-Cassel regiments and grenadier battalions have taken on [black men] as drummers [and] fifers[.]" 19/25

The Hessian muster rolls available at the Hessian State Archives in Marburg list approximately 125 individuals with black skin who served in Hessian forces during the American War of Independence. 20/25

Of the approximately 125 Black soldiers whose service was recorded, we known approximate dates of service for 56. Of these 56 soldiers, the average term of service was 2 years, some serving as long as six years and others serving for as short as 1 month. 21/25

It seems that some appeared to value their service as an end unto itself, while others simply viewed it as a pit-stop on the journey to freedom. 22/25

15-30 of these drummers serving in Hessian units returned to Europe; many of them died of disease. Others appear to have survived and married in Hessen. The Landgraf Friedrich II even became a god-parent to these some of these drummers and their children. 23/25

I hope that this post has respectfully showed some of the possible life experiences for black soldiers and musicians serving in European military forces during the eighteenth century. They faced incredible challenges, and suffered a lack of freedom. 24/25

However, for these men, like their white comrades, military service represented one of the few methods of changing their status in a world of relatively rigid hierarchies. Service remained an uncertain path on the road to freedom for African men in the eighteenth century. 25/25

For footnotes and image credits, see: kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2019/08/black-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh