⚠️#Java performance tip⚠️

Use primitive types instead of wrappers.

Java primitive types:

📍byte

📍short

📍int

📍long

📍float

📍double

📍char

📍boolean

More details and explanation in 🧵👇

Use primitive types instead of wrappers.

Java primitive types:

📍byte

📍short

📍int

📍long

📍float

📍double

📍char

📍boolean

More details and explanation in 🧵👇

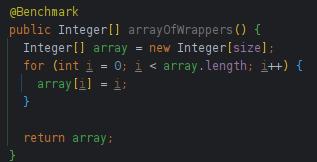

To show the difference in performance between primitive and wrapper objects I have created a benchmark which just creates an array of "int" and "Integer" and fills them with an index. Sizes of array: "10", "100", "1000", "10000"

Results: 👇

Results: 👇

Array of size 10:

❌ arrayOfWrappers 26.131 ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

❌ arrayOfWrappers 26.131 ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

Array of size 100:

❌ arrayOfWrappers ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

❌ arrayOfWrappers ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

Array of size 1000:

❌ arrayOfWrappers 26.131 ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

❌ arrayOfWrappers 26.131 ns/op - 2.7x slower

✅ arrayOfPrimitives 9.462 ns/op

Why primitive is more effective? Reasons:

- int requires 4 bytes, while Integer 16

- Integer is an object and creating objects is expensive

- primitive types reside in stack and fast to access, while objects are stored in heap.

🤓

- int requires 4 bytes, while Integer 16

- Integer is an object and creating objects is expensive

- primitive types reside in stack and fast to access, while objects are stored in heap.

🤓

That's a wrap!

If you enjoyed this performance tip:

1. Follow me @xpvit for more Java, Cloud, and Linux knowledge.

2. RT the tweet below to share this thread with your audience

If you enjoyed this performance tip:

1. Follow me @xpvit for more Java, Cloud, and Linux knowledge.

2. RT the tweet below to share this thread with your audience

https://twitter.com/421103460/status/1624363181022773248

Code can be found as usually on my GitHub: github.com/xp-vit/java-lo…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh