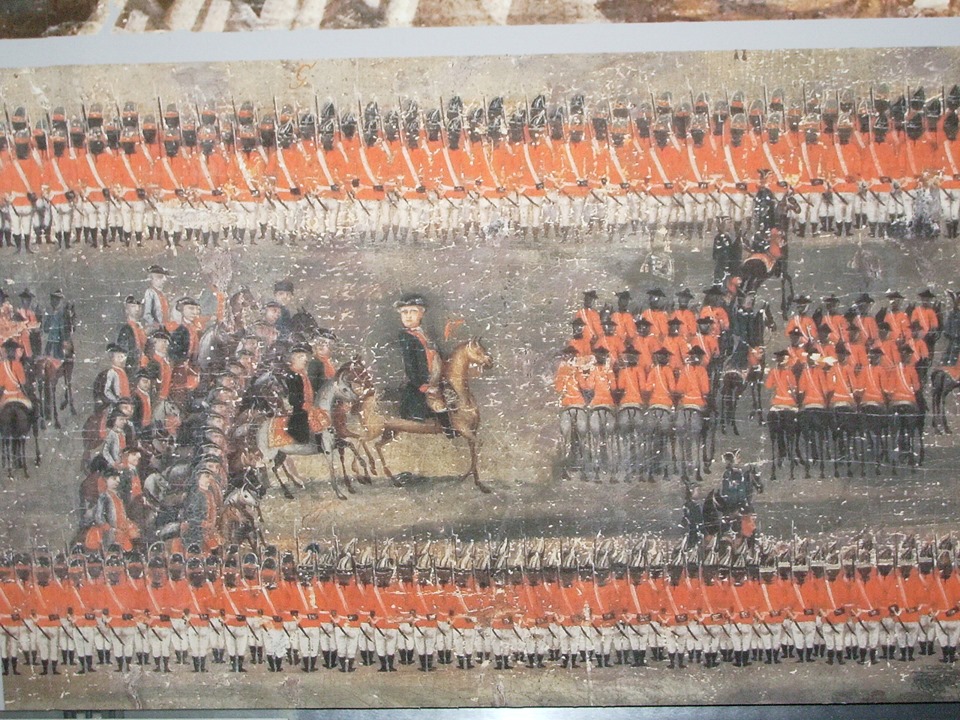

So, who had the best army in ~1720-1790 period, and why was it Russia? In all seriousness, as many of you pointed out, the poll was rather ridiculous, and the concept of “best” inane, but it was a fun way to generate some conversation on these armies. A poll results thread. 1/18

The concept of the best army in the world, of course, requires you to define the concept of best: do we mean victorious wars, tactical efficiency, great generals, power projection, logistical efficiency, or even quality of life for soldiers? 2/18

I'd like to spend this thread playing devil's advocate for the eighteenth-century Russian army. They got 3.5% Modern events impact historical thinking and we shouldn’t let chauvinism color our views of the past or the present. (“ah, Russians have always been idiots, right?”) 3/18

This thread shouldn’t be taken as pushing a “heroic” narrative of the Russian past. The leadership caste of this “Russian” army contained foreigners from all over Europe, many spoke German. This army was effective, but was a force that brought devastation and imperialism. 4/18

The Prussians won the vote, the British came in second. I’m not going to come after any of the other armies negatively: you could make a case for any of them, or the Habsburg/Austrian army, or the Afsharid army of Nadir Shah. 5/18

I'm going to define "best" with the following criteria:

A) Achievement and sustainment of strategic aims

B) Battlefield win-loss record

C) Quality of Higher Command

D) Logistical/Power Projection Abilities

E) Quality of Army Life for enlisted men 6/18

A) Achievement and sustainment of strategic aims

B) Battlefield win-loss record

C) Quality of Higher Command

D) Logistical/Power Projection Abilities

E) Quality of Army Life for enlisted men 6/18

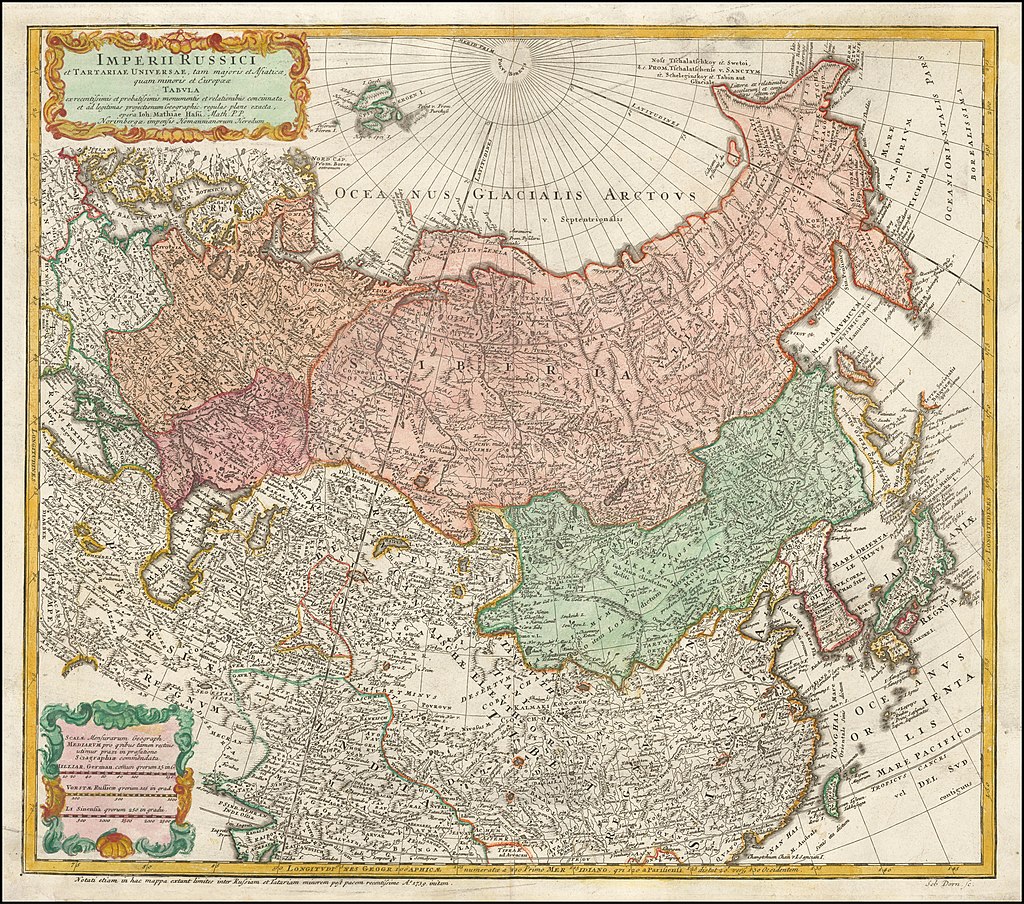

A) For the entire eighteenth century, the Russian military usually rose to the occasion in fulfilling and sustaining the political goals of the Tsars. Territory was successfully seized from Sweden, Poland, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire. 7/18

Regimes were upheld and overthrown in the Poland-Lithuania, the Ukrainian Hetmanate and Duchy of Courland were incorporated into the Empire, and rebellions from Bulavin to Pugachev were halted. France, Prussia, and Austria were checked in great power competition. 8/18

Wars that Russia lost, or didn’t win (Seven Years War, Russo-Turkish War of 1736-1739) didn’t result in large losses of territory. Regime change at home, or the fear of it, sometimes hampered military effectiveness abroad. 9/18

B) Even in wars where the overall objectives of the Russian Empire were not met Russian forces proved tactically proficient on the battlefield. The Prussian army that most of you voted for never fully defeated the Russians. 10/18

Even when Frederick II was personally in command, he found it "easier to kill the Russians" than defeat them. They experimented with specialist artillery, used buckshot more than other armies, and like the Austrians, retained special equipment for fighting the Ottomans. 11/18

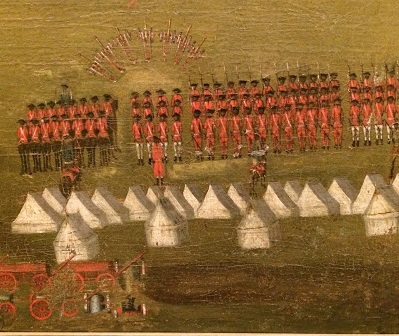

C) For most of this period, Russian generals lack the fame of Kutuzov or Zhukov, but they were often competent and efficient leaders. Peter I continued a longstanding tradition of importing foreign officers. This had positive effects. 12/18

Russian officer training was modernized in the 1730s by Prussians (including Steuben’s father) and for the rest of the century, Russian military men were highly competent. Few may remember the Münnichs, Buturlins, Fermors, and Rumyantsevs, but they provided solid direction. 13/18

Of course, the shining star of the leadership caste in this era is Suvorov, who many would put in the same (or higher) category as Frederick II of Prussia. Armies are more important than their shining stars, but they are memorable. 14/18

D) Russia projected power across Europe during this period. Russian soldiers were stationed near China. They marched to Berlin and supported troops as far away as the Netherlands. After failings in the Turkish War of 1736, they solved many of their logistical problems. 15/18

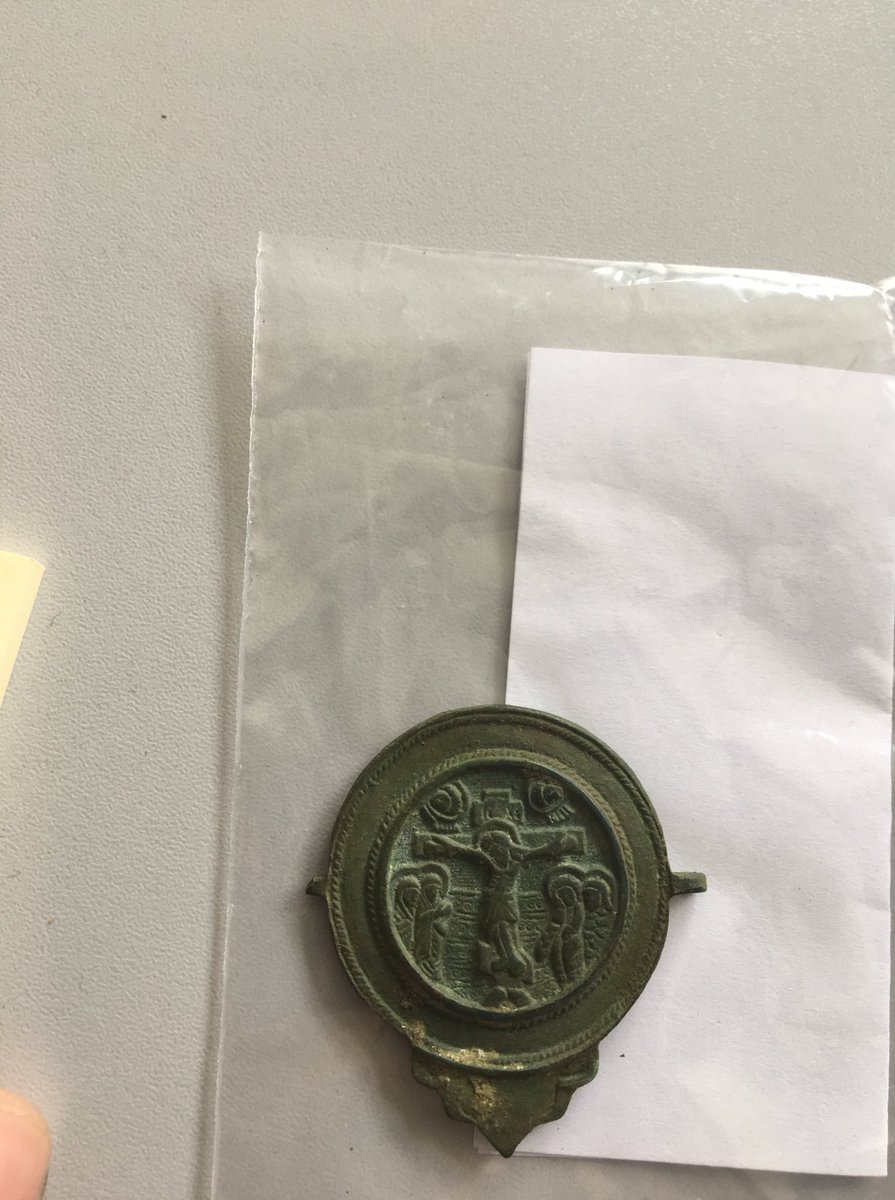

E) Russian soldiers were well paid until Catherine’s reign, able to marry, and a number were literate, particularly in the NCO corps. The artel system provided the men with a sense of community and the men maintained a rich spiritual life and belief in a “national God.” 16/18

“There was hardly one of the mortally-wounded Russians who had not clutched at the image of the patron saint which he wore about his neck, and pressed it to his lips while drawing his last breath.” Icons like this have been found via archeology at Kunersdorf. 17/18

Frederick lived in terror of the Russian military after 1758, the threat of their intervention ended the War of Bavarian Succession, and they triumphed over the Ottomans in the 1768 War. In 1774, the British preferred the Russians as subsidy-troops to go to America. 18/18

For a biography of an 18th century Russian officer who also happened to fight in the Napoleonic period, check out @AMikaberidze's Kutuzov: A Life in War and Peace. Alex is one of those rare historians who is gob-stoppingly brilliant and also a nice person irl.

Also, read anything that you can get your hands on by Brian L. Davies: his book on the entirety of the 18th century is great, and his book on the 1768 War taught me alot.

Also, last but not least, its old, but Christopher Duffy's "Russia's Military Way to the West" is still one of the great works on the longer period. A wonderful man, we lost Christopher last year.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh