🧵of 🧵

We've covered most of the commonly used sutures...now it's time for Nylon.

Most of us associate Nylon with skin closure, and that is what it's used for most of the time, but there are a few other uses.

As usual, we'll go over its properties, and so on.

(1/ )

We've covered most of the commonly used sutures...now it's time for Nylon.

Most of us associate Nylon with skin closure, and that is what it's used for most of the time, but there are a few other uses.

As usual, we'll go over its properties, and so on.

(1/ )

This is from a 1942 Annals of Surgery article.

Nylon was first made in 1938 by Dupont as a substitute for silk. Since surgeons already liked to use silk sutures, it immediately occurred to them to try to use Nylon sutures as well.

Nylon was first made in 1938 by Dupont as a substitute for silk. Since surgeons already liked to use silk sutures, it immediately occurred to them to try to use Nylon sutures as well.

Nylon suture is monofilament and glides through tissue easily, making it useful for skin closure.

It's also nonabsorbable, meaning that it will have to be cut out, or else the skin will eventually grow over it. It's rarely used internally, as normally there are better options.

It's also nonabsorbable, meaning that it will have to be cut out, or else the skin will eventually grow over it. It's rarely used internally, as normally there are better options.

Other advantages of Nylon are that it's strong and tissue reactivity is mild.

The biggest disadvantage is that the knots are among the most difficult to tie of all suture materials.

This is especially the case with larger nylon sutures, like 0 or 2-0.

The biggest disadvantage is that the knots are among the most difficult to tie of all suture materials.

This is especially the case with larger nylon sutures, like 0 or 2-0.

I usually tie 5-6 knots, often using a slip knot or surgeon's knot at the beginning.

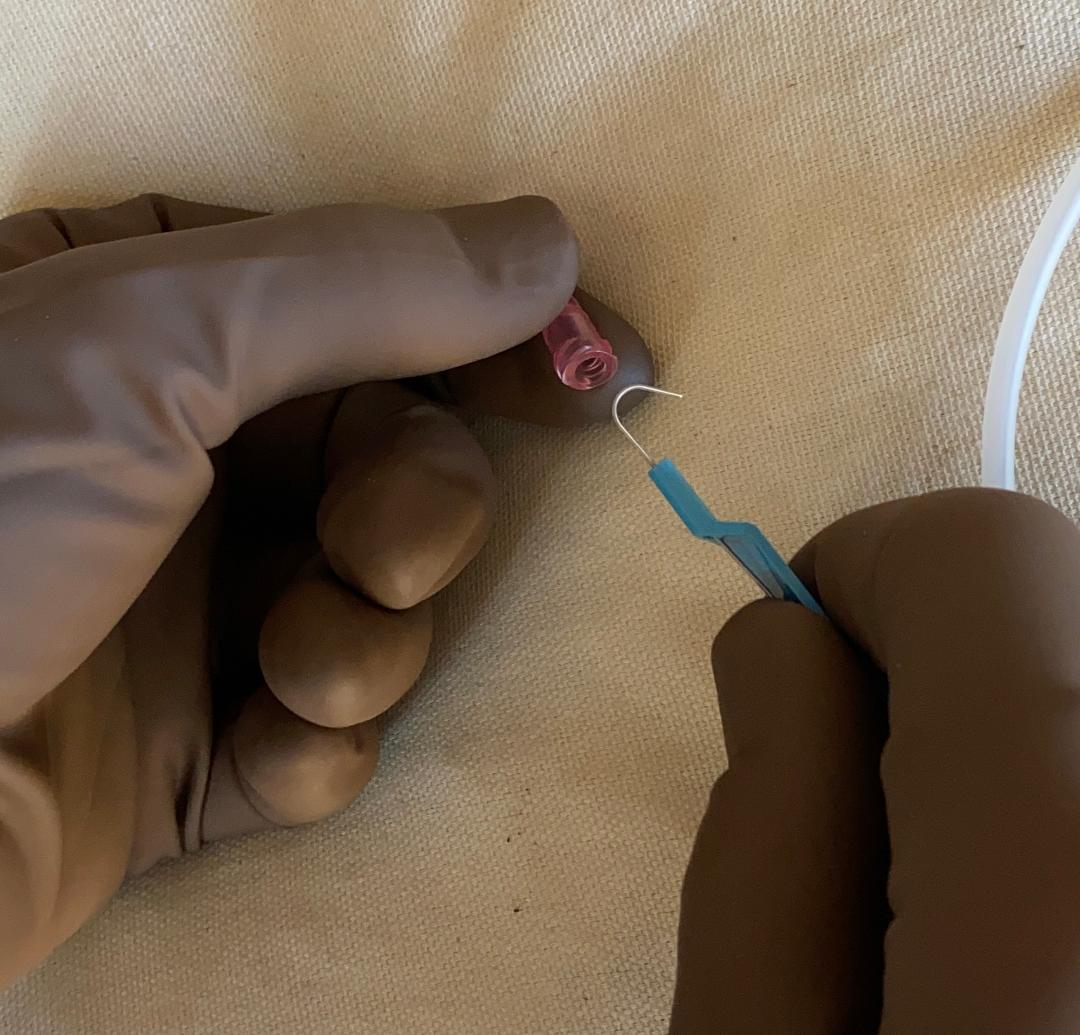

Tails are cut about this long, at least for larger nylon sutures (this is 2-0 Nylon). With smaller sutures (like 5-0 for example), the tails can be shorter.

Tails are cut about this long, at least for larger nylon sutures (this is 2-0 Nylon). With smaller sutures (like 5-0 for example), the tails can be shorter.

When the Nylon suture tails are left too long (L picture), they often get in the way when doing the next suture (R picture).

Either the knot will be compromised, or you have to spend time tediously fishing the annoying string out of there (and probably also trimming it).

Either the knot will be compromised, or you have to spend time tediously fishing the annoying string out of there (and probably also trimming it).

Nylon sutures are rather stiff and it is easy to leave 'air knots' when tying.

Here you can see that I have tied knots that seemed fine at the time, but now that it’s finished you can see there are several air knots.

These look bad and are more likely to become undone.

Here you can see that I have tied knots that seemed fine at the time, but now that it’s finished you can see there are several air knots.

These look bad and are more likely to become undone.

It's tempting to compensate for this by just pulling the sutures tighter, and in doing so it often happens that they get pulled too tight.

Here, I have eliminated of the air knots, but now the sutures are pulling too hard on the tissue. At the least, it will leave an ugly mark.

Here, I have eliminated of the air knots, but now the sutures are pulling too hard on the tissue. At the least, it will leave an ugly mark.

When closing skin with nylon, there is also a tremendous tendency for the first throw to spring apart due to the tension from the tissues, as I am trying to simulate here.

There are various ways to overcome this, but this would probably need to be its own separate thread.

There are various ways to overcome this, but this would probably need to be its own separate thread.

The largest size Nylon is #2.

I use it to close skin of the chest or abdomen in trauma patients who have died intraoperatively.

There are reports of using it to close rectus fascia in urologic procedures. I don't recommend using nonabsorbable suture for fascial closure.

I use it to close skin of the chest or abdomen in trauma patients who have died intraoperatively.

There are reports of using it to close rectus fascia in urologic procedures. I don't recommend using nonabsorbable suture for fascial closure.

#1 Nylon exists, and was once used to close fascia, which cannot be endorsed now.

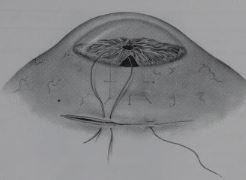

#1 or 0 Nylon has been used to ‘whip stitch’ the abdominal skin closed after damage control laparotomy (as described by Dissanaike). Note that the fascia itself remains open.

#1 or 0 Nylon has been used to ‘whip stitch’ the abdominal skin closed after damage control laparotomy (as described by Dissanaike). Note that the fascia itself remains open.

Nylon sizes 2-0 through 6-0 are almost always used to close skin of different thicknesses.

2-0 might be used on the thick skin of the back or thigh. 3-0 is good for skin in many areas. 5-0 or 6-0 might be used for the face and for closing skin on small children.

2-0 might be used on the thick skin of the back or thigh. 3-0 is good for skin in many areas. 5-0 or 6-0 might be used for the face and for closing skin on small children.

Looking through all the Nylon sutures on the rack, one notices that almost all of them are on cutting needles. This is consistent with its usual role in skin closure.

You only start seeing taper point needles once you get down into ophthalmology range (8-0 and smaller).

You only start seeing taper point needles once you get down into ophthalmology range (8-0 and smaller).

Nylon also tends to come on rather large needles. It's hard to fully appreciate in the photo, but this is a pretty big needle for a 3-0 suture.

The large needles have the advantage that it's easier to close skin by 'taking' both edges with a single bite.

The large needles have the advantage that it's easier to close skin by 'taking' both edges with a single bite.

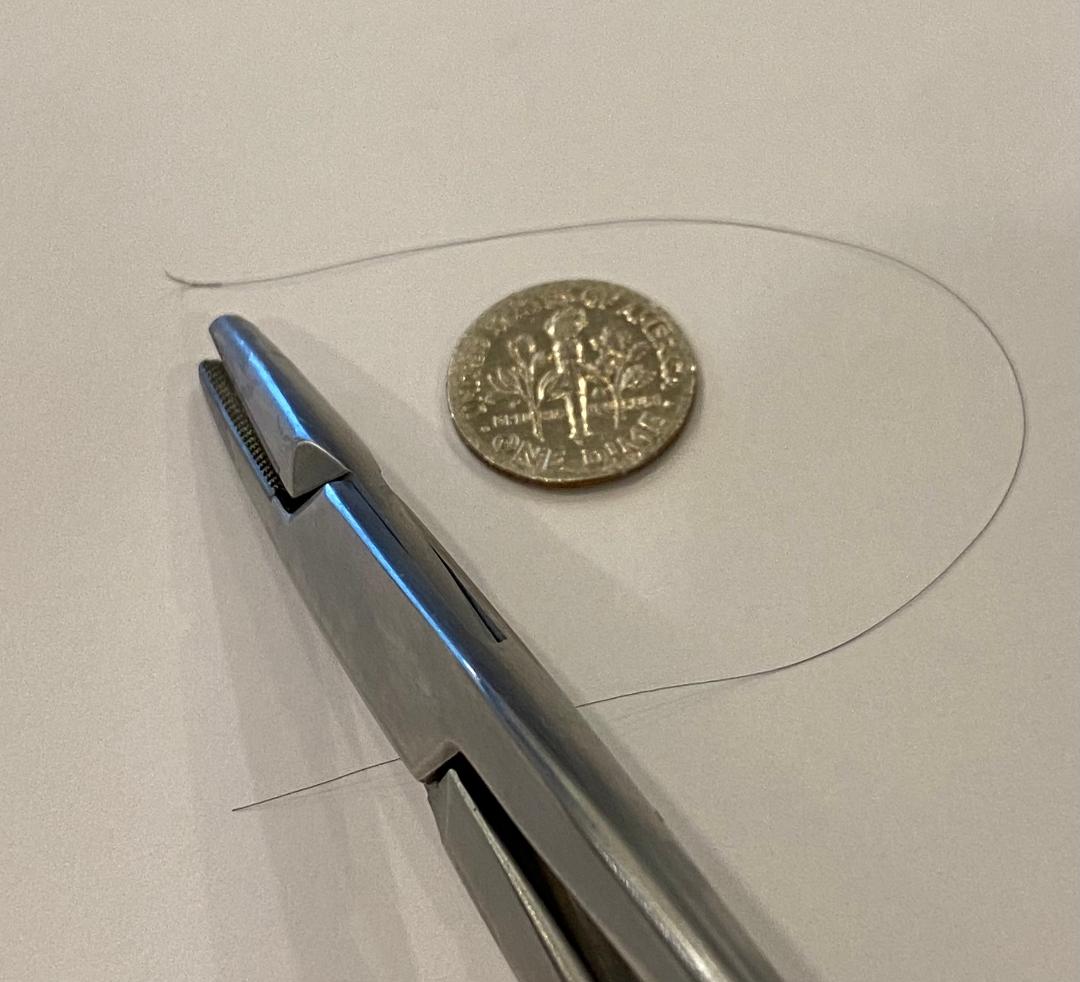

Here is an 8-0 Nylon on one of the smallest needles, next to a standard size needle holder (which you wouldn't use) for reference.

8-0 Nylon is used in ophthalmologic procedures, and I also found references describing its use in peripheral nerve surgery and for vasovasostomy.

8-0 Nylon is used in ophthalmologic procedures, and I also found references describing its use in peripheral nerve surgery and for vasovasostomy.

Nylon goes all the way down to 9-0, 10-0 and 11-0.

It's easier to manufacture at these sizes than many other sutures, so that's part of the reason why it features in microsurgery.

Uses that I can find include eye surgery, vasovasostomy, and peripheral nerve surgery.

It's easier to manufacture at these sizes than many other sutures, so that's part of the reason why it features in microsurgery.

Uses that I can find include eye surgery, vasovasostomy, and peripheral nerve surgery.

It is worth noting that the black color of Nylon sutures can make them hard to find when removing them if they are buried in dark hair, such as in a scalp laceration.

In these cases it may be better to use Prolene, which is blue, and is much easier to find and remove.

In these cases it may be better to use Prolene, which is blue, and is much easier to find and remove.

Finally, there is also a braided version of nylon called Nurulon. As you might expect, it's *much* easier to tie.

4-0 Nurulon has been used to close dura in brain and spine cases, and to close neck muscle layers during C-spine surgery.

⬛️

4-0 Nurulon has been used to close dura in brain and spine cases, and to close neck muscle layers during C-spine surgery.

⬛️

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh