I always optimize space on my electronics and hardware security workbench by using small and portable tools.

Here are some that I use that didn’t exist a few years ago, and are much smaller and/or cheaper than their traditional alternatives;

#hamradio

#electronics

#hwhacking

🧵

Here are some that I use that didn’t exist a few years ago, and are much smaller and/or cheaper than their traditional alternatives;

#hamradio

#electronics

#hwhacking

🧵

FlipperZero is an open source portable multi-tool: NFC/RFID reader/emulator, IR transceiver, sub-GHZ transceiver (CC1101 based) , SPI/UART tool, and much more.

It can even function as a U2F token!

More info here: flipperzero.one

@flipper_zero

#flipperzero

It can even function as a U2F token!

More info here: flipperzero.one

@flipper_zero

#flipperzero

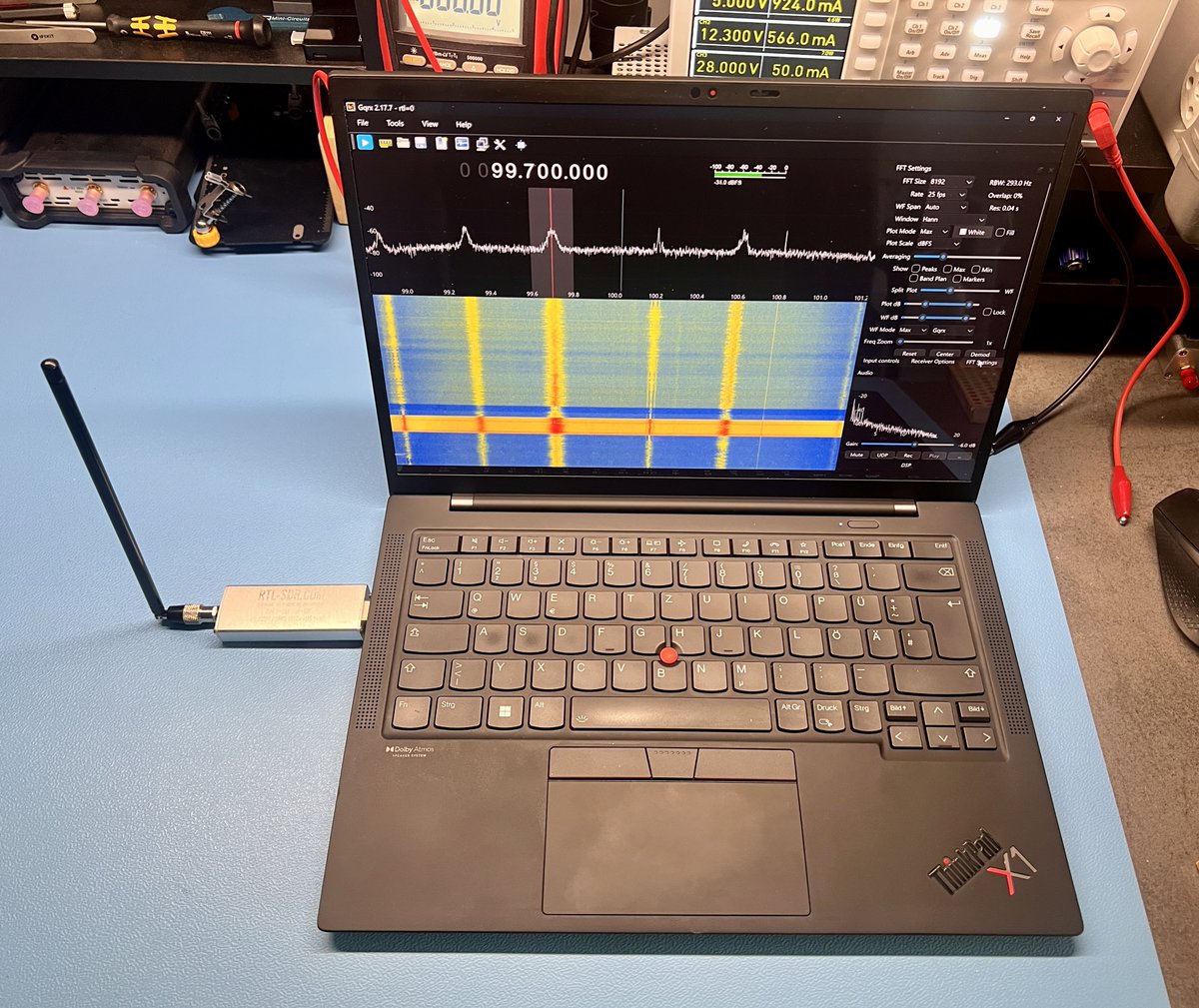

TinySA Ultra: small spectrum analyzer with a 4" screen, covering 100 KHz to 6 GHz. Also works as a signal generator.

TinySA.org

TinySA.org

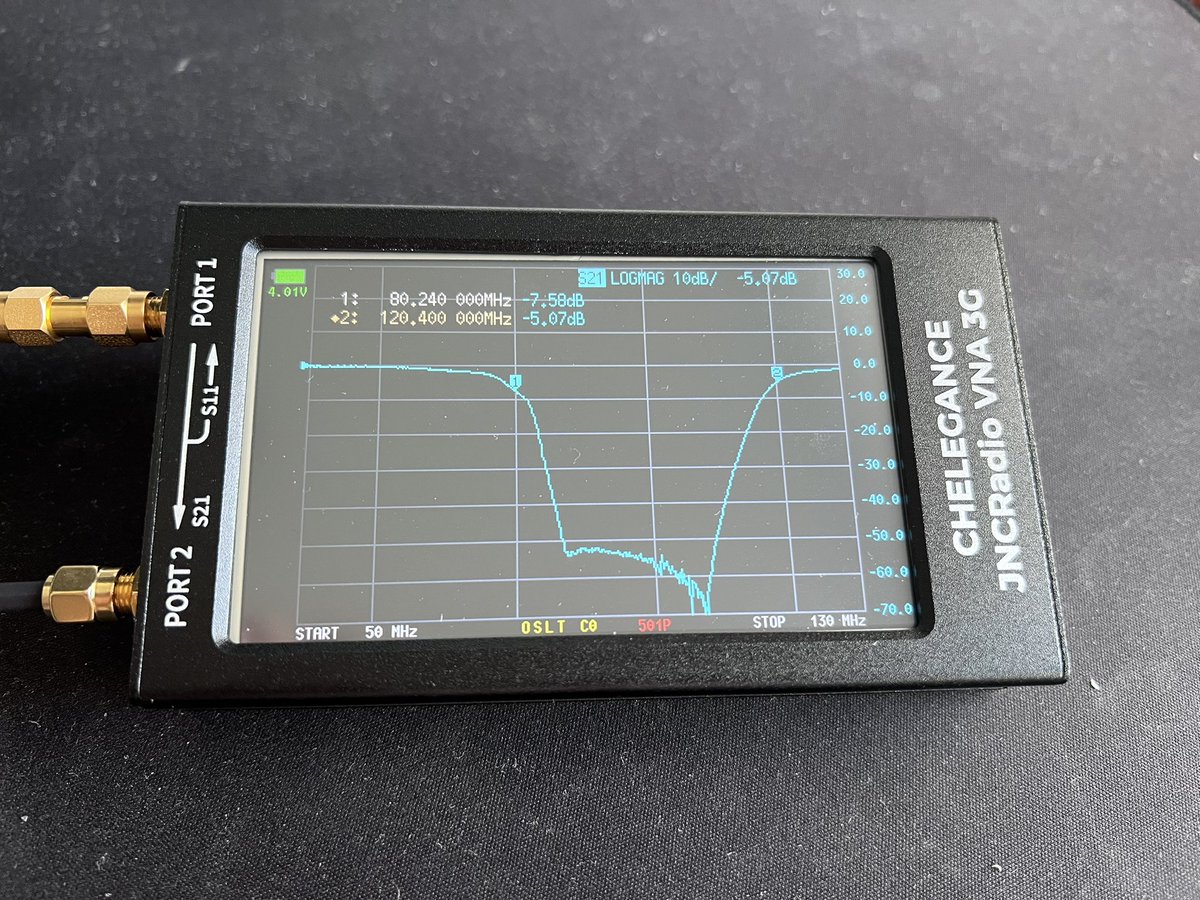

NanoVNA family: a portable VNA. Comes in different sizes, brands and prices. Mine covers 50 KHz to 3 GHz.

ERASynth Micro: open source signal generator covering 12 MHz to 6 GHz. Was crowd funded on @crowd_supply

Pinecil: portable soldering iron. Can be powered by DC barrel jack or USB-C.

Made by @thepine64

I haven't used my Ersa station since I got this!

Made by @thepine64

I haven't used my Ersa station since I got this!

Another product from Miniware: programmable & stackable DC power supply. The picture shows 3 products: MDP-P906 a 300W module in the bottom, MDP-P905 a 90W one in the middle, and MDP-M01 the control module on top.

They can also operate independently (without the control module)

They can also operate independently (without the control module)

Tigard: an open source multi protocol tool for hardware hacking designed by @securelyfitz

Supports UART, SWD, JTAG, SPI, I2C.

Supports UART, SWD, JTAG, SPI, I2C.

Portapack: add-on board for HackRF One to turn it into a portable SDR. Designed by @sharebrained

There are a few firmware options to choose from (I use mayhem)

There are a few firmware options to choose from (I use mayhem)

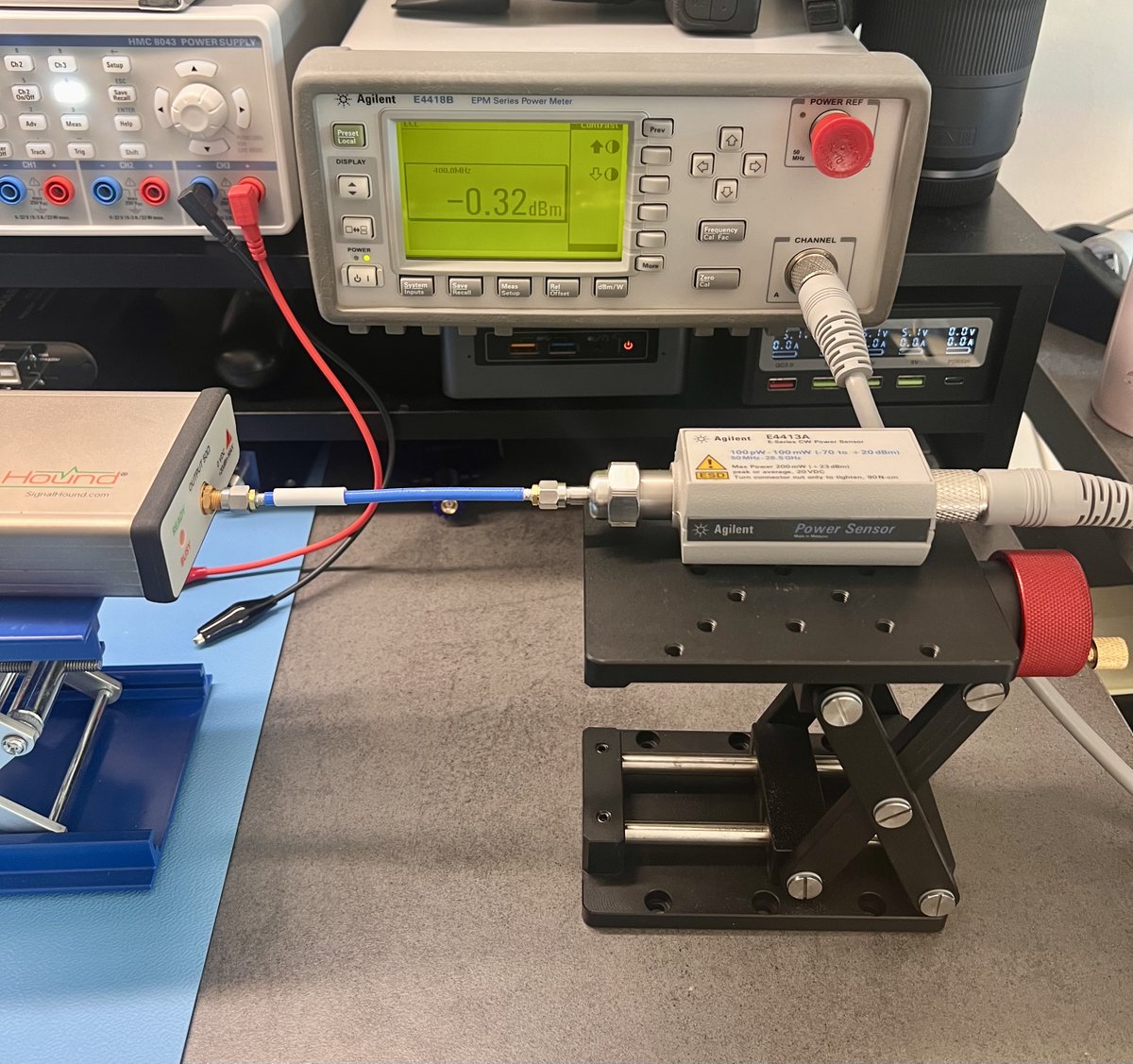

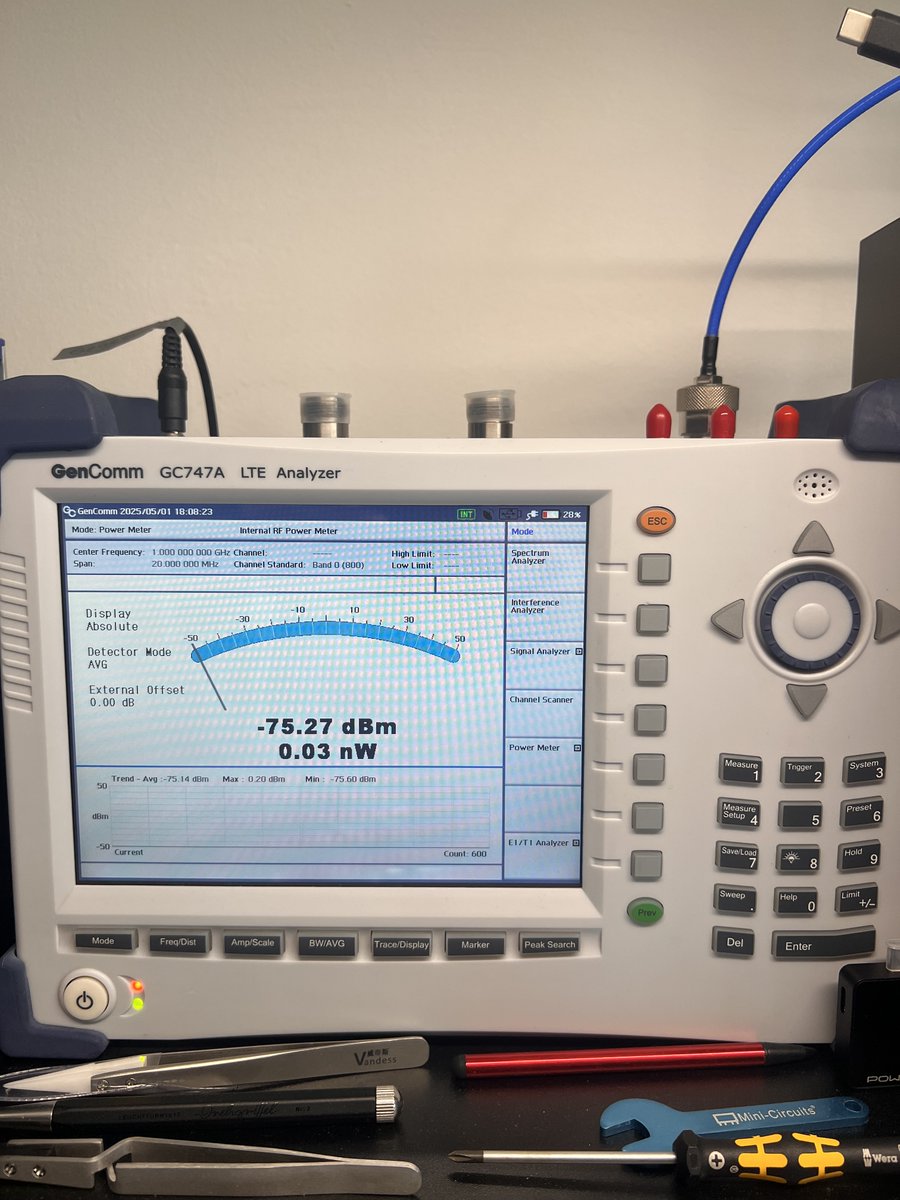

RF Power Meter by ImmersionRC.

Can measure the calibrated frequencies: 35, 72, 433, 868, 915, 1200, 2400, 5600-6000 MHz

Runs on the internal battery and has an internal 30dB attenuator.

Can measure the calibrated frequencies: 35, 72, 433, 868, 915, 1200, 2400, 5600-6000 MHz

Runs on the internal battery and has an internal 30dB attenuator.

@newaetech's products. Depicted here: PhyWhisperer-USB: USB hacking device (sniffing, fuzzing, fault injection). ChipWhisperer Lite: side channel power analysis tool. PicoEMP: electromagnetic fault injection tool (ChipShouter's low-cost sibling)

PCBite by @SensePeek

A kit containing magnetic PCB holders and probes with compressible needles to help in hands-free measurements (using a multimeter, logic analyzer or oscilloscope on a device)

A kit containing magnetic PCB holders and probes with compressible needles to help in hands-free measurements (using a multimeter, logic analyzer or oscilloscope on a device)

It's important to keep in mind that not all of these tools can compete with more professional alternatives (especially the measurement tools), however considering the price, I've found them very useful and accurate enough for hobbyist/DIY/amateur use cases.

End of the 🧵

End of the 🧵

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh