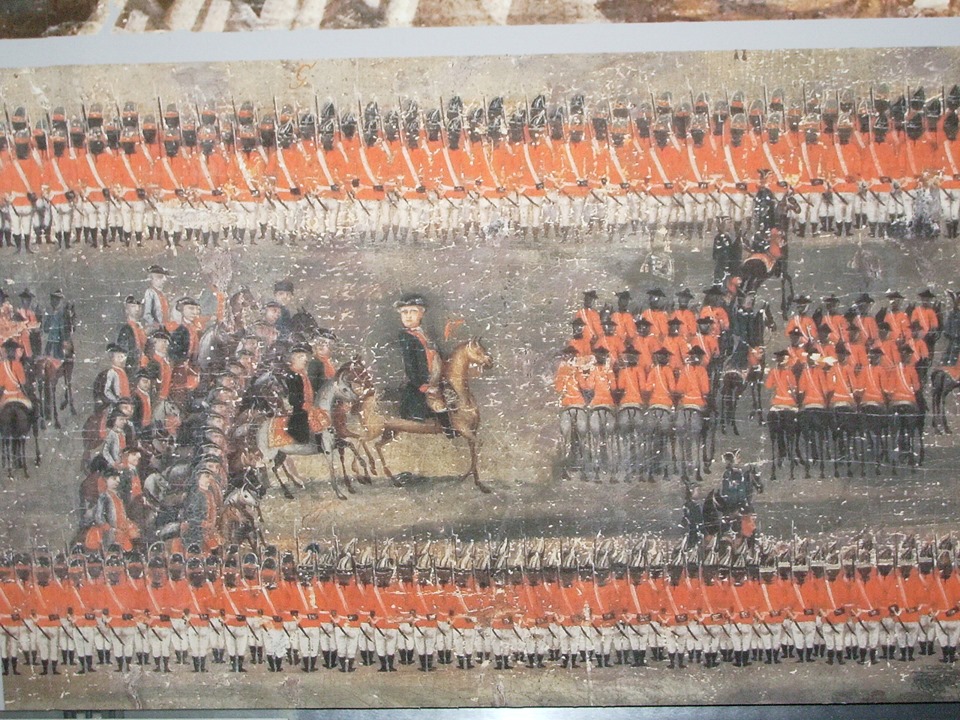

A Melee Monday Thread. The classic depiction of eighteenth-century warfare is troops marching into close range, firing a few volleys, and charging with bayonets. How frequent was melee (hand to hand) combat in this era? TL;DR, troops didn't fight in hand to hand very often. 1/28

Melee combat occurred, but it was less frequent than we might think. I am sure we can all think of famous examples: Culloden, Bunker Hill, and Guilford Courthouse stand out. When fighting the Ottoman Empire, both Russian and Austrian soldiers reported fierce melees. 2/28

Many military commanders, at some point in their careers, seemed to prefer a cold steel attack. Frederick the Great advocated this idea in the early Seven Years' War, Alexander V. Suvorov famously stated that, "the bullet is a mad thing, put your trust in the bayonet." 3/28

With these ideas spreading, surely hand to hand combat was frequent? n reality, hand-to-hand, or melee combat was limited to a select number of places. When enemy troops appeared to make a serious advance into close range with bayonets, defending troops often melted away. 4/28

That is why the Swedish Karoliner and British redcoats proved so effective on their respective battlefields. It also why when things went wrong for troops making a charge with cold steel, they went very wrong (such as at Poltava in 1709 and Cowpens in 1781.) 5/28

Troops did experience hand-to-hand combat, but firepower (at range) was the order of the day. In William Dalrymple's 1782 essay on tactics, he asserted (in the case of infantry): 6/28

There is probably not an instance of modern troops being engaged in close combat... the bayonet can be of little utility...in the field...two battalions...being brought in the open field to close encounter: one body must give way before they get into action. 7/28

Though Dalrymple is exaggerating for effect, we would be wise to take his point. In the open field, when flight was a possibility, it was rare for two battalions of infantry to cross bayonets. 8/28

French military authority Jacques Antoine de Guibert understood the issue in this way:

"Soldiers have become familiar with bayonets, and view them as an unnecessary arm. They consider it to be a weapon without a use... 9/28

"Soldiers have become familiar with bayonets, and view them as an unnecessary arm. They consider it to be a weapon without a use... 9/28

Soldiers, and French soldiers above all, believed, "Well, I am out of ammunition, so only bayonets are left."...our troops always march with fixed bayonets, in a unique way, a weapon that is always ready but never used." 10/28

In short, during cavalry action, attacks on defensive works, and surprise attacks, troops often engaged in melee combat. These were the places for bayonets, not in the open field against other infantry. 11/28

When cavalry troops were involved, melee combat was quite frequent. At Guilford Courthouse, William Washington's light dragoons savaged the British 2nd Guards.[3] One of these light dragoons, Peter Francisco gave us a window in the visceral intensity of this type of combat: 12/28

“Colonel Washington, observing their maneuvering, made a charge upon them, in which charge he (Francisco) was wounded in the thigh by a bayonet, from the knee to the socket of the hip, and in the presence of many, he was seen to kill two men[.]'" 13/28

When fighting other cavalry, it appears that the horses would seek intervals through the enemy formation, leading to brief moments of intense combat followed by maneuvering. Even here, however, cavalry melee was perhaps less effective than frequently believed. 14/28

In the 1780s, military theorists studying the Prussian army recorded, "We heard from some cavalry officers that when troops undertake a charge, almost always, one troop flees before melee is joined, and the other gives pursuit." 15/28

Georg Tempelhof, a veteran of the Seven Years' War, reported: "The strength of cavalry consists in its movement: it must have the ability to maneuver with speed. The shock or charge has no effect unless it happens in this way... 16/28

Forgive me if I do not consider the cavalry's shock to be so decisive as it seems. In 1762 I observed Prussian cavalry charging superior Austrian horsemen. The result was that on both sides there were a few hundred wounded and prisoners. Not a single death was recorded." 17/28

When defending soldiers held fortified or prepared positions, melee combat could be fierce. Soldiers attached great psychological important to their defensive works, and often tangled with enemy troops in melee combat in order to defend them. 18/28

Troops often fought with bayonets during surprise attacks or "massacres." The American War of Independence produced a number of famous night-attacks which led to bayonet fighting, both of these, at Paoli in 1777 and Tappan in 1778 were extremely violent affairs. 19/28

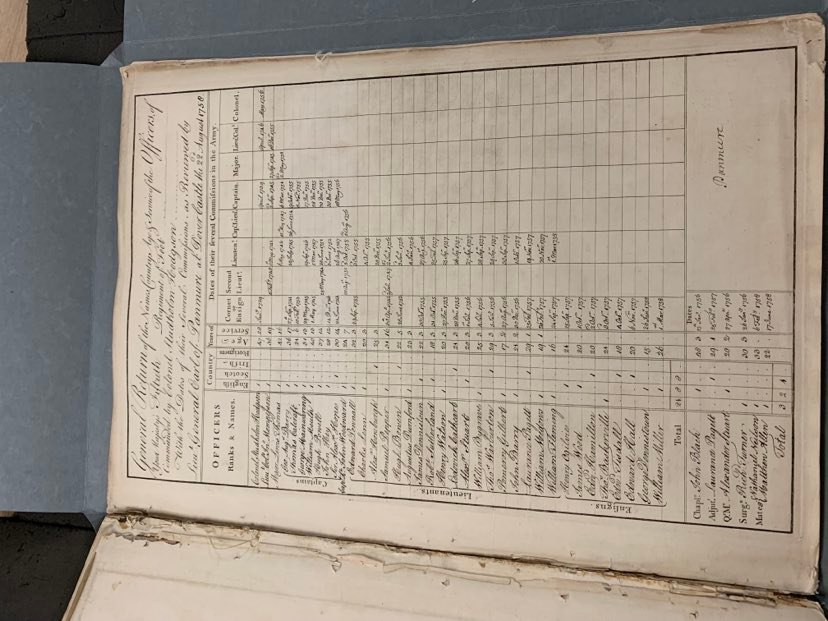

At the Battle of Hochkirch in 1758, Austrian columns overran the Prussian camp before some Prussians were even awake. Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz, a Prussian veteran, described what it was like the be on the receiving end of such a swift-moving attack: 20/28

"It was dark, and confusion reigned supreme. What a sight for these warriors, almost like a night terror. The Austrians seemed to emerge from the earth, in the midst of the...center of camp! Several hundred men were killed before they could open their eyes... 21/28

...and others ran half-naked to their weapons. Only a few could reach them. Others laid ahold of whatever was closest to hand, and began to fight." 22/28

So, did infantry in the open really not cross bayonets? It was quite rare. According to one French report, 68.8% percent of troops were wounded by small arms fire, 14.7% were wounded by artillery fire, and approximately 15% were wounded by swords and bayonets. 23/28

When we consider that swords were the cavalry's main form of engaging the enemy, these figures are impressive. J. F. Puysegur argued that: "firearms are the most destructive category of weapon, and now more than ever... 24/28

...If you need convincing, just go to the hospital and you will see how few men have been wounded by cold steel as opposed to firearms. My argument is not advanced lightly. It is founded on knowledge." 25/28

Because Puysegur was writing in the 1740s, before the Seven Years' War, his experience is even more telling. Other military theorists, such as David Dundas, recalled, "... infantry seldom mix with bayonets." 26/28

At the battle of the third line at Guilford Courthouse, we see infantry attempting to load and fire while in melee combat. Cpt. Smith of the 1st Maryland found himself in melee combat against the British guards, but was shot at close range by a soldier who had just loaded. 27/28

Obviously, melee occurred in the eighteenth century. However, it was not a common occurrence, and seems to have become less prevalent over the course of the era.

As always, footnotes= kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2018/02/did-me… 28/28

As always, footnotes= kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2018/02/did-me… 28/28

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh