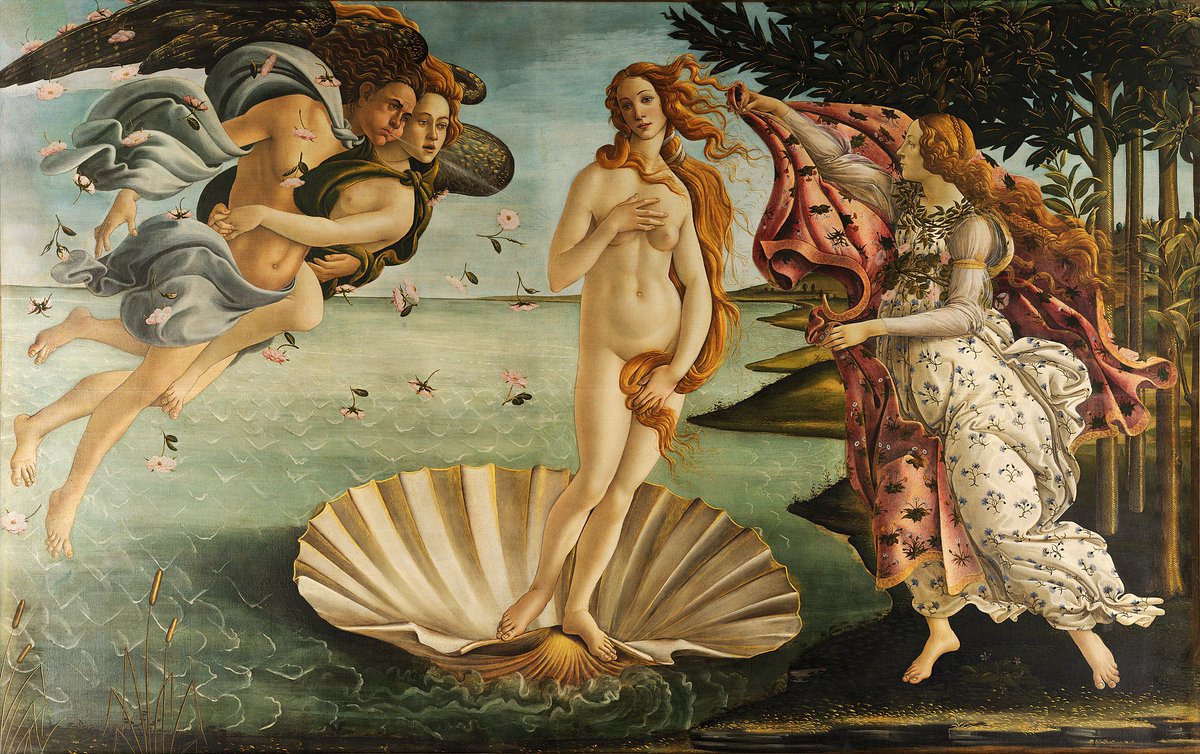

The Birth of Venus, painted by Sandro Botticelli in 1485, is one of the world's most famous and beloved paintings.

But it was completely forgotten for nearly four hundred years because nobody thought it was any good.

So... what changed?

But it was completely forgotten for nearly four hundred years because nobody thought it was any good.

So... what changed?

Alessandro Filipepi was born in Florence in 1445, just as the Italian Renaissance was bursting into life.

From a young age he showed natural artistic talent and was apprenticed to a goldsmith called Botticelli.

That's where Sandro got the surname he is known by.

From a young age he showed natural artistic talent and was apprenticed to a goldsmith called Botticelli.

That's where Sandro got the surname he is known by.

But Sandro preferred painting, and so his father sent him to work with Fra Filippo Lippi, one of the foremost painters in Florence at that time.

The style of Filippo Lippi, as in the painting below, had a huge influence on young Botticelli.

The style of Filippo Lippi, as in the painting below, had a huge influence on young Botticelli.

Soon enough he started to find his own style and in 1470 announced himself in the competitive world of Florentine art with this painting, called Fortitude.

Thereafter he was never short of commissions, whether for churches or wealthy patrons, such as the Medici family.

Thereafter he was never short of commissions, whether for churches or wealthy patrons, such as the Medici family.

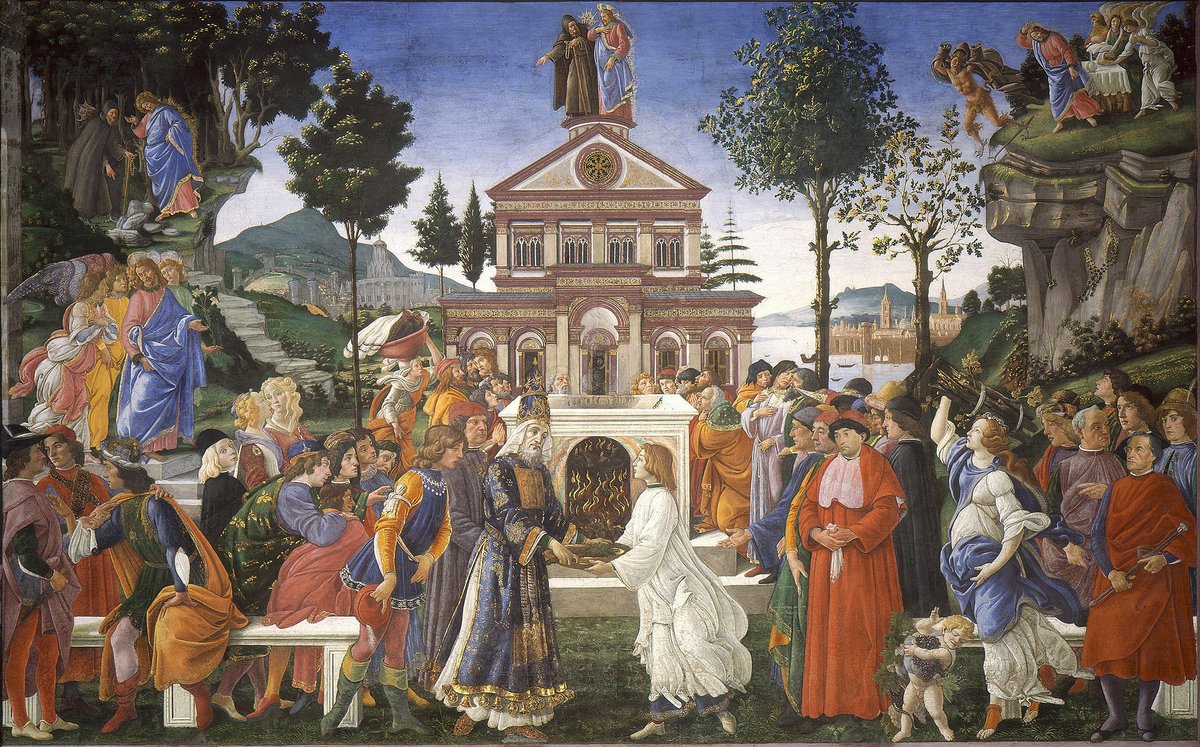

In 1481 Pope Sixtus IV commissioned Botticelli, along with several other leading artists, to decorate his newly completed Sistine Chapel in Rome, which says much about Botticelli's growing reputation.

His work there, like his master Lippi, was full of rich colours and details.

His work there, like his master Lippi, was full of rich colours and details.

But Botticelli didn't just paint Christian religious scenes - he was fascinated by the classical world of Greece and Rome, whether historical or mythological.

Such as the Judgment of Paris, a mythical prelude to the Trojan War of Greek legend.

Such as the Judgment of Paris, a mythical prelude to the Trojan War of Greek legend.

Botticelli also became renowned for his many paintings of Mary and the infant Jesus.

These Madonnas, with their elegant gowns and carefully arranged locks of blonde hair, show his love for pastel tones, sumptuous fabrics, and flowers.

These Madonnas, with their elegant gowns and carefully arranged locks of blonde hair, show his love for pastel tones, sumptuous fabrics, and flowers.

And Botticelli's portraits tell us much the same. He stands out among other Renaissance artists as being chiefly interested in loveliness.

Quite unlike the intellectual zeal of his contemporaries, Botticelli prized pearls, curly hair, and delicacy.

Quite unlike the intellectual zeal of his contemporaries, Botticelli prized pearls, curly hair, and delicacy.

His style changed in the 1490s, growing darker and more austere as Florence itself went through turbulent times.

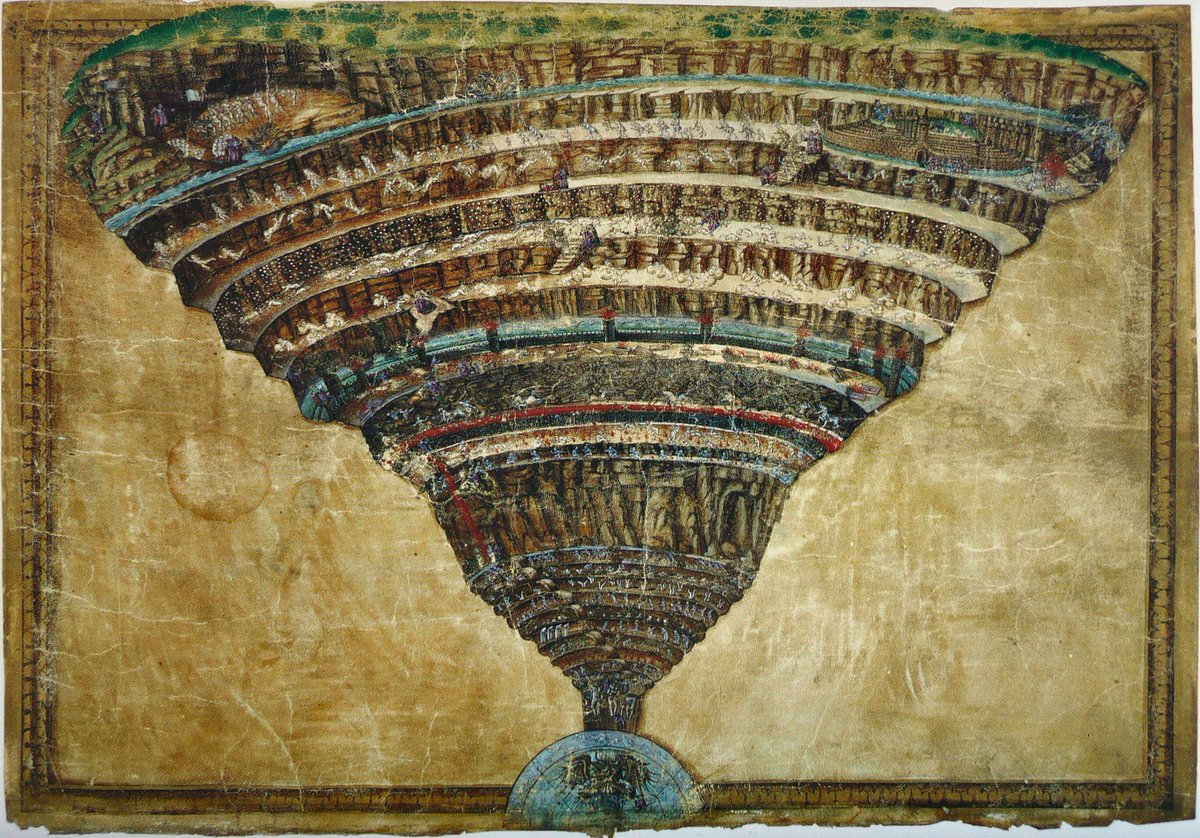

He started painting less, too, and spent his time making drawings of Dante's Inferno, apparently disillusioned and reclusive; he died in 1510.

He started painting less, too, and spent his time making drawings of Dante's Inferno, apparently disillusioned and reclusive; he died in 1510.

In his own time Botticelli ran a large workshop and amassed enough fame and respect to be written about several decades later by the biographer and historian Giorgio Vasari.

But after that Botticelli faded from history, consigned to the obscurity of so many artists...

But after that Botticelli faded from history, consigned to the obscurity of so many artists...

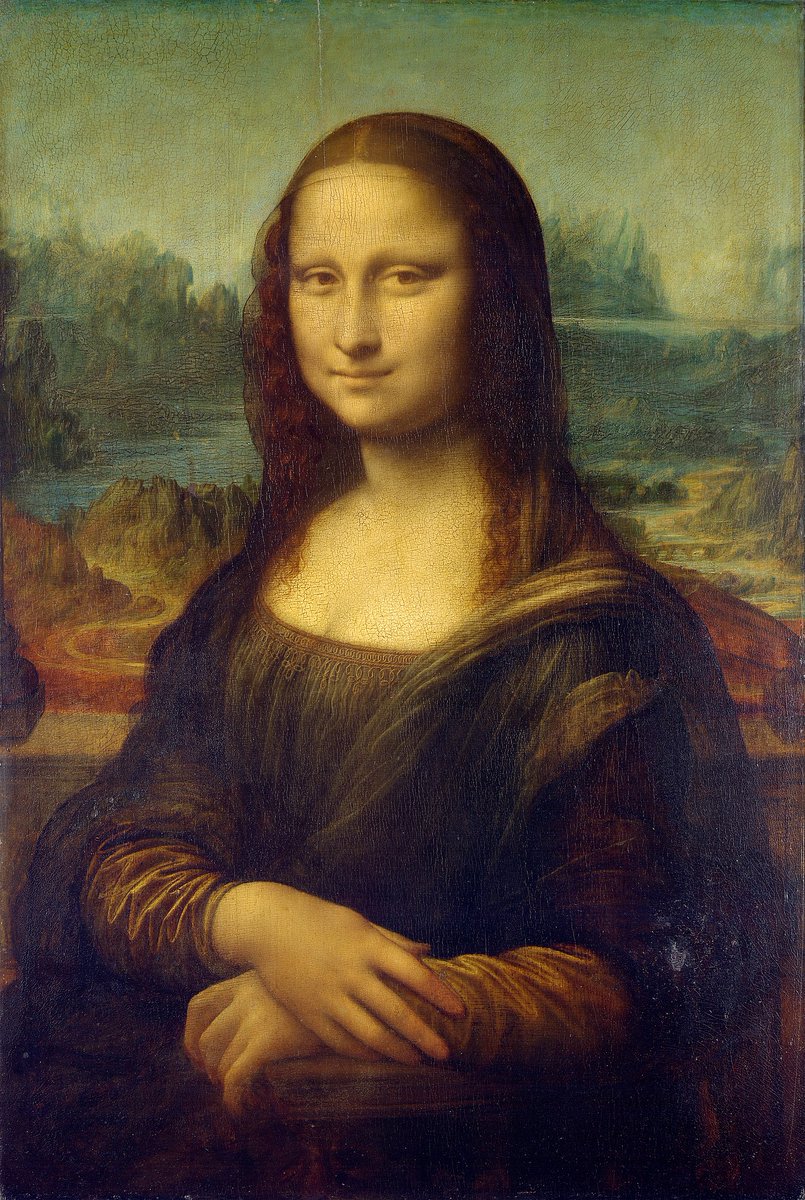

Why? Because of three men: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

This titanic triumvirate loom not only over the Renaissance but over all western art; their greatness overshadowed all those who had come before.

This titanic triumvirate loom not only over the Renaissance but over all western art; their greatness overshadowed all those who had come before.

And how could they not?

We need only compare Botticelli's paintings in the Sistine Chapel to those done by Michelangelo in the same place thirty years later.

Early Renaissance art looks stiff and lifeless by comparison, inelegant and crowded with needless detail.

We need only compare Botticelli's paintings in the Sistine Chapel to those done by Michelangelo in the same place thirty years later.

Early Renaissance art looks stiff and lifeless by comparison, inelegant and crowded with needless detail.

Of the three it was Raphael who was considered the greatest, and that consensus lasted for several hundred years.

But in the 19th century things were changing, and an unknown artist called Sandro Botticelli started drawing the attention of visitors to Florence...

But in the 19th century things were changing, and an unknown artist called Sandro Botticelli started drawing the attention of visitors to Florence...

By the end of the 1800s Botticelli had become the famous and much-loved artist he is today.

Which is where the Birth of Venus comes in, a full statement of Botticelli's style, blending the Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance into a unique world of beauty and mystery.

Which is where the Birth of Venus comes in, a full statement of Botticelli's style, blending the Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance into a unique world of beauty and mystery.

A group of English artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites saw in Botticelli something which was lacking in Raphael, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

While those three had brought an unforetold realism, grace, and power to art, their "cleaner" style had come at a cost.

While those three had brought an unforetold realism, grace, and power to art, their "cleaner" style had come at a cost.

Botticelli was still touched by that Medieval spirit, not so interested in the maths of perspective and shading, human anatomy, or visual clarity as a love for colour, natural beauty, and a sort of fantastical symbolism where his meaning was never obvious.

Take Botticelli's La Primavera, filled with Medieval decoration and detail, all flowers and fruits and elegant robes and translucent silks, floating and dream-like.

There's something here we do not find in Raphael, Leonardo, or Michelangelo - delightfulness & enigma.

There's something here we do not find in Raphael, Leonardo, or Michelangelo - delightfulness & enigma.

We can see what the Pre-Raphaelites meant when we look at Raphael's painting of a scene from classical mythology, The Triumph of Galatea.

Its anatomical realism makes it looks rather unpleasant and overly serious when compared with Botticelli's free and fanciful Birth of Venus.

Its anatomical realism makes it looks rather unpleasant and overly serious when compared with Botticelli's free and fanciful Birth of Venus.

Such fancifulness came from Gothic art like that of the Limbourg Brothers.

It was this spirit Botticelli channelled, even when depicting scenes from classical mythology and using Renaissance techniques.

What's remarkable is that he harmonised those three different worlds.

It was this spirit Botticelli channelled, even when depicting scenes from classical mythology and using Renaissance techniques.

What's remarkable is that he harmonised those three different worlds.

Leonardo was precise and Michelangelo was mighty, but neither was romantic.

Unlike Botticelli, whose paintings portrayed a form of romance inherited from the Medieval notion of courtly love.

Unlike Botticelli, whose paintings portrayed a form of romance inherited from the Medieval notion of courtly love.

Raphael sought visual clarity, naturalism, and humanist grace.

But those high artistic ideals and a pursuit of realism became a prison which didn't allow for the delightful details, allegory, flowing hair, floating figures, and enchanting mysteries of Botticelli.

But those high artistic ideals and a pursuit of realism became a prison which didn't allow for the delightful details, allegory, flowing hair, floating figures, and enchanting mysteries of Botticelli.

He was forgotten for centuries, overshadowed by the giants of the High Renaissance.

But his delightful visions of romance and myth give us something they never could.

And it was this realisation of what had been lost that, finally, brought Botticelli his deserved fame.

But his delightful visions of romance and myth give us something they never could.

And it was this realisation of what had been lost that, finally, brought Botticelli his deserved fame.

This is the sort of thing I write about in my free Friday newsletter.

To join 70k+ other readers and make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

To join 70k+ other readers and make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh