🧵regarding the terminology of some common suture needle types.

This is a revised version of a 🧵I did several months ago (I’ve been on vacation 😎, and it’ll be a bit untiI I have new material).

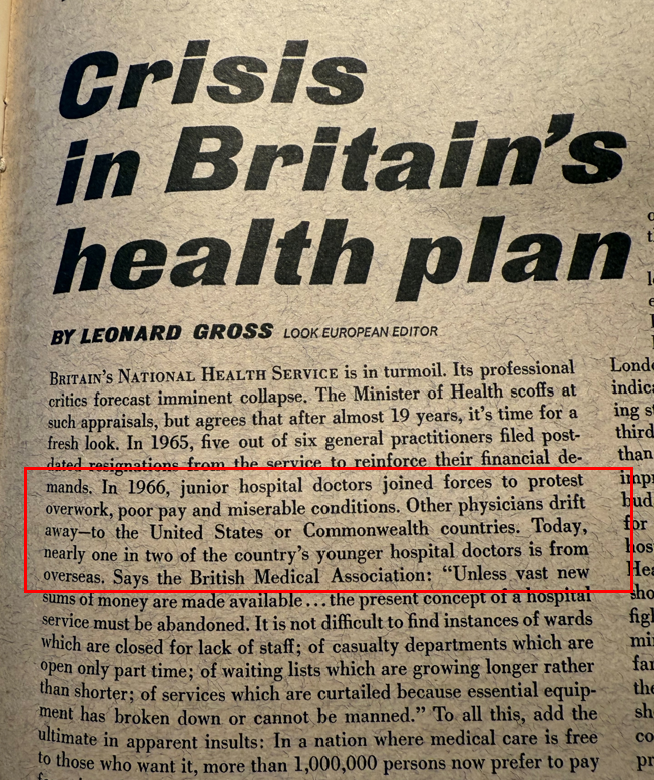

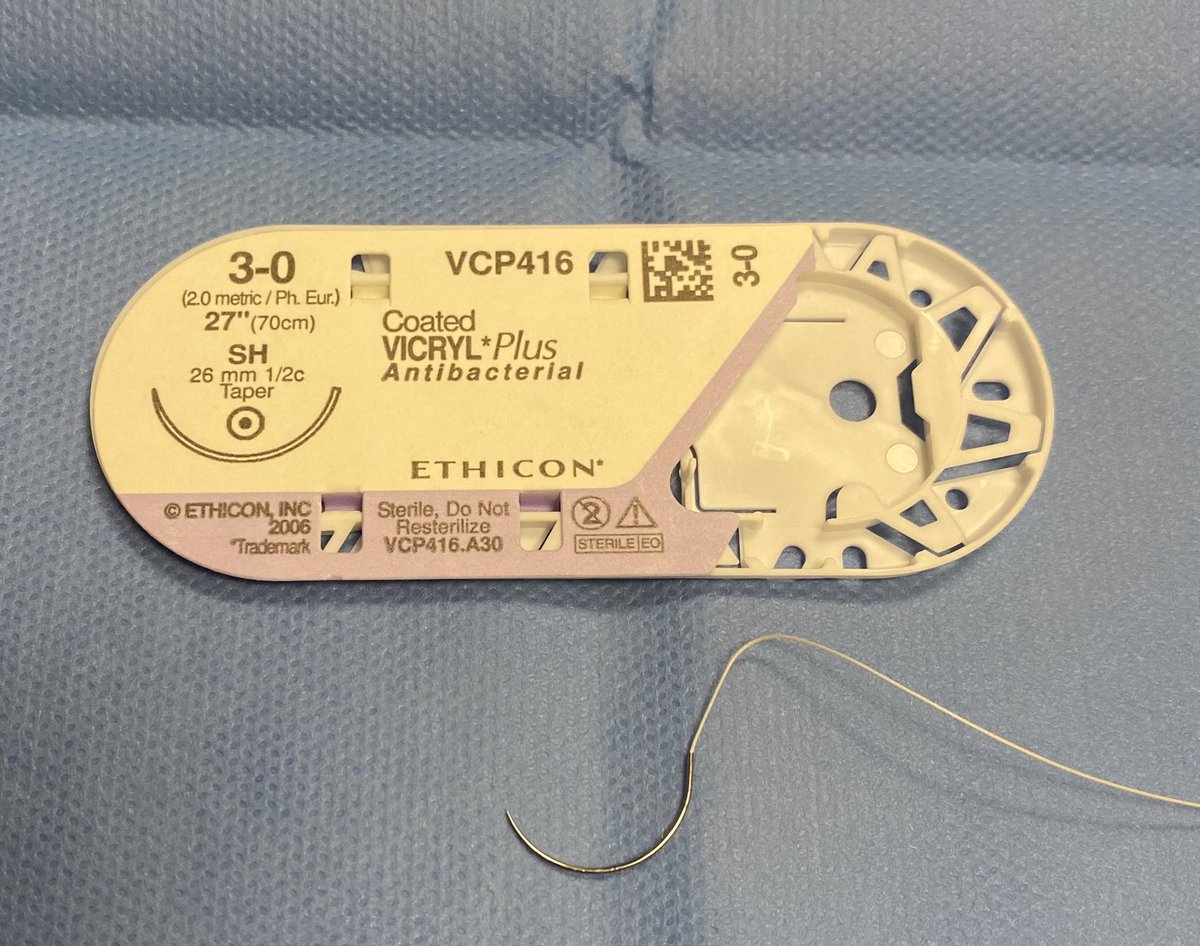

This is the ubiquitous SH needle we all know. But what does SH stand for?

(1/ )

This is a revised version of a 🧵I did several months ago (I’ve been on vacation 😎, and it’ll be a bit untiI I have new material).

This is the ubiquitous SH needle we all know. But what does SH stand for?

(1/ )

Note: This thread pertains only to Ethicon needles, which is what we have at my hospital. Other companies have other systems.

Shown here is the chart from the Ethicon manual. Each of the letter combinations has a specific meaning, and most of these make at least some sense.

Shown here is the chart from the Ethicon manual. Each of the letter combinations has a specific meaning, and most of these make at least some sense.

Going back to the SH needle again…It’s a taper point needle in the form of a half circle. The SH is the shortest of these at 26 mm, so it’s called ‘Short Half’ (circle).

Its increasingly larger alternatives include the MH, LH, XLH, and XXLH.

Its increasingly larger alternatives include the MH, LH, XLH, and XXLH.

CT stands for ‘Circle Taper’.

Again, as the name implies, these are also tapered needles. There is the CT (40 mm) and then the CT-1 is a little smaller at 36 mm. There is also a CT-2 (not shown - it is 26 mm).

Again, as the name implies, these are also tapered needles. There is the CT (40 mm) and then the CT-1 is a little smaller at 36 mm. There is also a CT-2 (not shown - it is 26 mm).

PS stands for ‘plastic surgery’.

This is a PS-1. It continues with PS-2 and PS-3, which are smaller. These are 3/8 circle and are *reverse cutting* needles, appropriate for skin closure.

PS-4, -5, and -6 exist, and these are slightly different at 1/2 circle (click to enlarge).

This is a PS-1. It continues with PS-2 and PS-3, which are smaller. These are 3/8 circle and are *reverse cutting* needles, appropriate for skin closure.

PS-4, -5, and -6 exist, and these are slightly different at 1/2 circle (click to enlarge).

Prolene sutures often come on a BV needle which stands for...wait for it...

'Blood vessel' 🤔

BV-1 is very common, but there are a few variants. All of the BV needles are 3/8 circle and have a tapered point, and the variation is in the length.

'Blood vessel' 🤔

BV-1 is very common, but there are a few variants. All of the BV needles are 3/8 circle and have a tapered point, and the variation is in the length.

The famous UR-6 needle. It is **5/8 circle**. The 'UR' stands for ‘urology’.

Its unusual 5/8 circle curvature makes it useful for operating down in the confined space of the pelvis. General surgeons also use it to close trocar site fascia.

UR-5 and UR-4 exist, and are larger.

Its unusual 5/8 circle curvature makes it useful for operating down in the confined space of the pelvis. General surgeons also use it to close trocar site fascia.

UR-5 and UR-4 exist, and are larger.

This is the monstrous ‘BP’ or ‘blunt point’ needle.

Unlike a tapered needle, the BP needle does not have a sharp point...the point is blunt on purpose.

#1 Chromic on a BP is used to suture liver lacerations, and the blunt tip helps avoid cutting of the liver parenchyma.

Unlike a tapered needle, the BP needle does not have a sharp point...the point is blunt on purpose.

#1 Chromic on a BP is used to suture liver lacerations, and the blunt tip helps avoid cutting of the liver parenchyma.

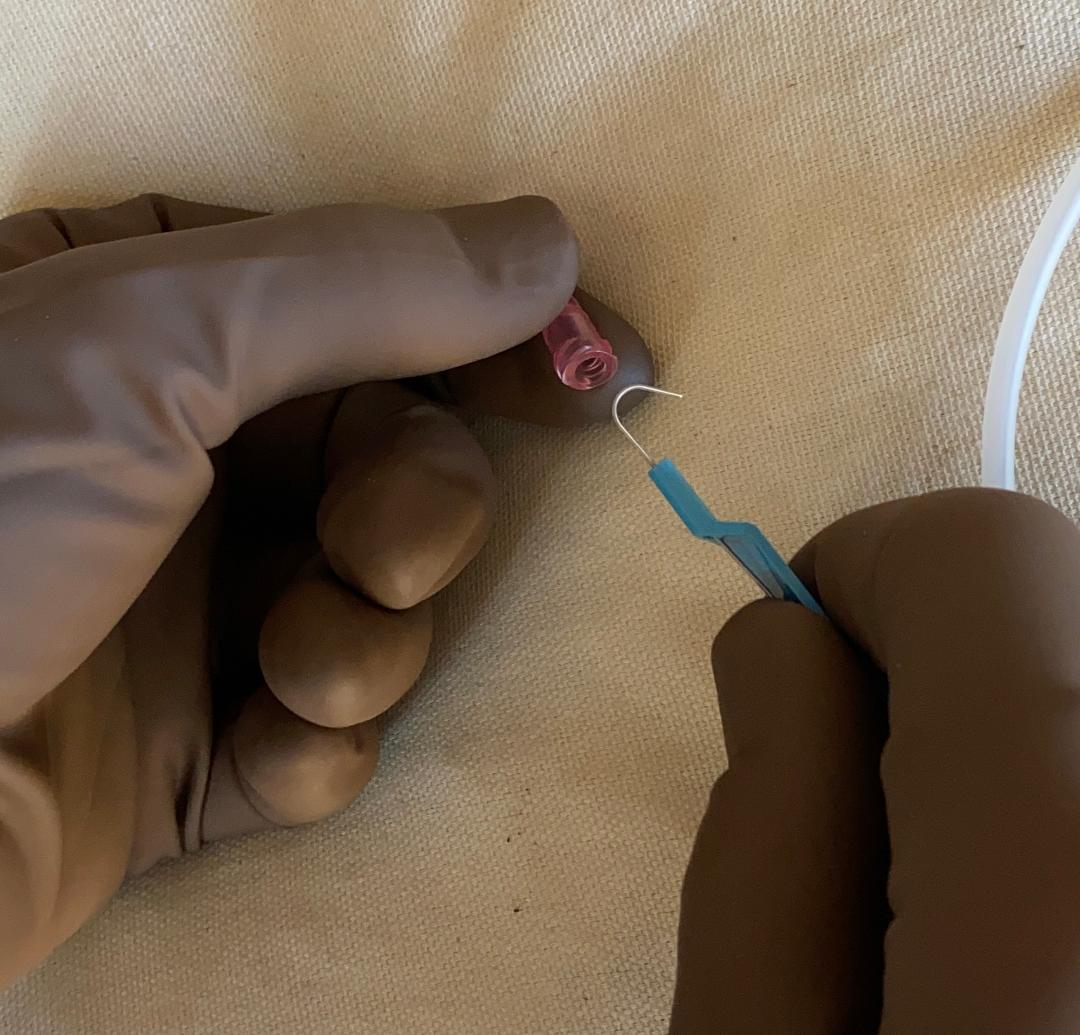

4-0 Monocryl is a good example of where needle types matter.

The reverse cutting PS-1 on the left is appropriate for subcuticular skin closure, but if the Monocryl is being used to sew on the bowel, it would not do well at all, and a (tapered) SH needle would be much better.

The reverse cutting PS-1 on the left is appropriate for subcuticular skin closure, but if the Monocryl is being used to sew on the bowel, it would not do well at all, and a (tapered) SH needle would be much better.

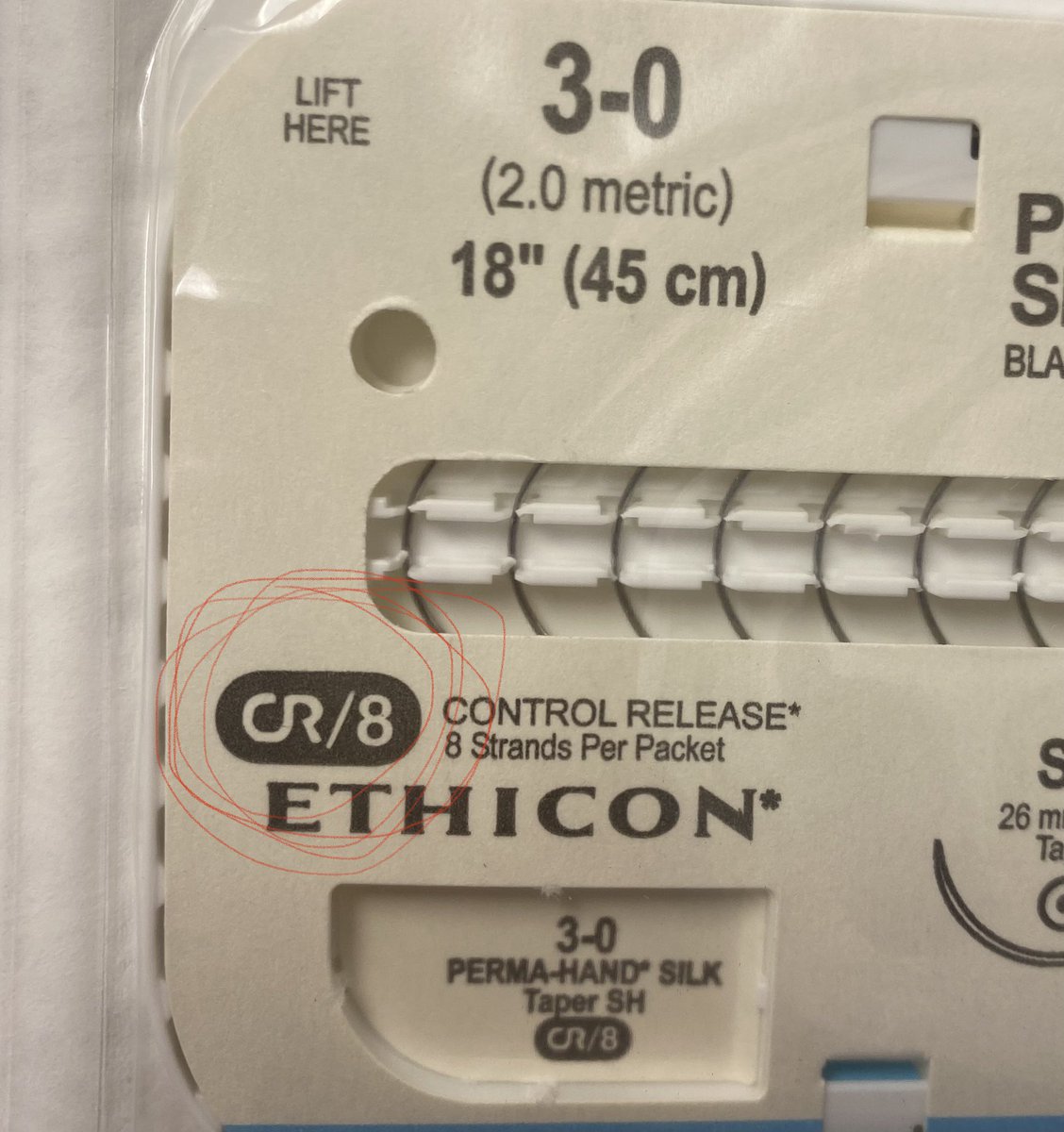

This symbol stands for ‘controlled release’. In the US, these are more commonly called ‘popoffs’.

'Popoffs' usually come in packs of several needles and are designed to easily pop off when the suture is pulled, so that one can skip the extra step of cutting the needle off.

'Popoffs' usually come in packs of several needles and are designed to easily pop off when the suture is pulled, so that one can skip the extra step of cutting the needle off.

This is a Keith needle (‘KS’ in Ethicon terminology).

The Keith is a long, straight reverse cutting needle, often used to grab big bites of tissue for sewing in drains (or central lines)

Its main advantage is that you don't need a needle holder to use it.

The Keith is a long, straight reverse cutting needle, often used to grab big bites of tissue for sewing in drains (or central lines)

Its main advantage is that you don't need a needle holder to use it.

Charts that compare needle types among different companies also exist, and may be found in a more readable form on the Internet.

Finally, both curved and straight needles are also packaged by themselves.

These are 'Richard-Allan' needles, and as you can see, these have to be loaded with suture material in the same way that non-medical sewing needles are.

⬛️

These are 'Richard-Allan' needles, and as you can see, these have to be loaded with suture material in the same way that non-medical sewing needles are.

⬛️

Addendum:

This is beyond the scope of the 🧵but since I mentioned 'reverse cutting' needles:

These have a cutting surface on the convex side of the needle, and actually are much more common than 'conventional' cutting needles (that have a cutting surface on the concave side).

This is beyond the scope of the 🧵but since I mentioned 'reverse cutting' needles:

These have a cutting surface on the convex side of the needle, and actually are much more common than 'conventional' cutting needles (that have a cutting surface on the concave side).

Addendum #2:

I don't know what the 'Twisty Q' needle is used for.

It only comes on 0 Ethibond, and the needle itself is also black in color. It's obviously a specialty item.

I don't know what the 'Twisty Q' needle is used for.

It only comes on 0 Ethibond, and the needle itself is also black in color. It's obviously a specialty item.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh