This week - in my ongoing series "Is That Thing You Eat Everyday Secretly Killing You?!" - #Erythritol!

I want to dig into a nice @NatureMedicine paper that suggests the sugar substitute might increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Thread/)

I want to dig into a nice @NatureMedicine paper that suggests the sugar substitute might increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Thread/)

Erythritol is a non-nutritive sweetener used in all sort of products - toothpaste, gum, especially "keto friendly" stuff. Also monkfruit sweetener. It does NOT need to be labeled "artificial" since it can be found (in small quantities) in nature.

Data all comes from this paper @NatureMedicine - definitely a cut above your usual nutritional epidemiology fare - multiple lines of evidence here to tease out.

nature.com/articles/s4159…

nature.com/articles/s4159…

The researchers started with a metabolomic analysis of ~1000 people being screened for CV disease. Seems the focus was on sugar / sugar substitute metabolites but erythritol came out on top as most strongly associated with subsequent CV events.

Of course, this would need to be validated in an external dataset. Researchers did this too, finding in a US cohort, for example, that those in the highest quartile of erythritol levels had higher rates of CV disease over time.

But... correlation or causation, right? They adjusted for stuff like age, diabetes, BMI, etc - but still - people who use a lot of sugar substitutes are likely different in non-measurable ways from people who don't.

But what if there *is* causality here. How would that work? The researchers show that, in a test tube, higher levels of erythritol lead to increased aggregation of platelets (clotting, basically).

And in a model of carotid artery occlusion (in mice), erythritol speeds to the occlusion process... so there's at least some biologic plausibility here.

But if I've learned anything reviewing sugar substitute literature - it's to check the dosages. Just because you can give a rat cancer giving it 1000x the daily intake of some sugar substitute does not mean it is clinically relevant.

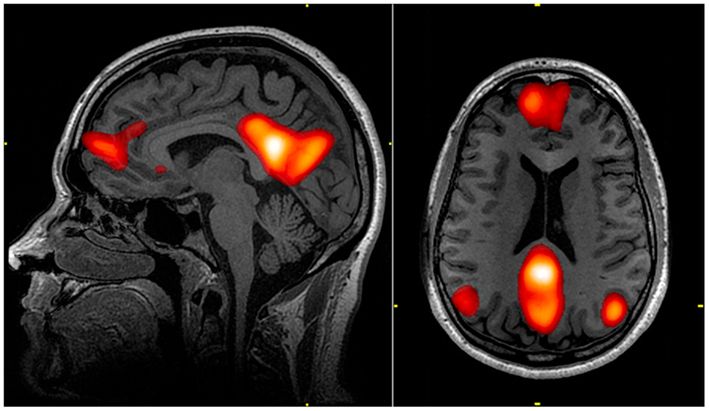

I'll use 45 uM as a "concentration of interest" here - since that appears to be the place where we see some of that platelet aggregation. Is that a reasonable concentration? The authors gave 8 healthy controls 30grams of erythritol and this is what the blood levels did:

After 30grams of intake - you can get super-high levels - persisting above 45 uM for almost 2 days. (This is likely based a bit on kidney function - 90% of erythritol is excreted unchanged in the urine).

But... is 30grams reasonable? The authors argue that 30grams is the average daily intake in the US based on this FDA document - but it looks like that's actually the 90th percentile...

And a european study (of people who exclusively use sugar-free foods / drinks) show intake levels way lower than that.

How much is 30 grams? Turns out I had a bag of erythritol in my closet.

I don't think most people get close to 30grams of erythritol - likely much much less - unless you are deep in the "keto" ecosystem. I therefore don't think we need to worry about the potential risk too much.

Remember, the risks of artificial sweeteners should not be evaluated in a vacuum - they need to be compared to the alternative - sugar - which is probably the single substance most responsible for the epidemic of overweight, obesity, metabolic syndrome, T2D, etc.

Still, there is a truism in the diet research space here. You probably can't have your (sugar-free) cake and eat it too.

I wrote more about this for my column on @Medscape this week:

medscape.com/viewarticle/98…

(/thread)

medscape.com/viewarticle/98…

(/thread)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh