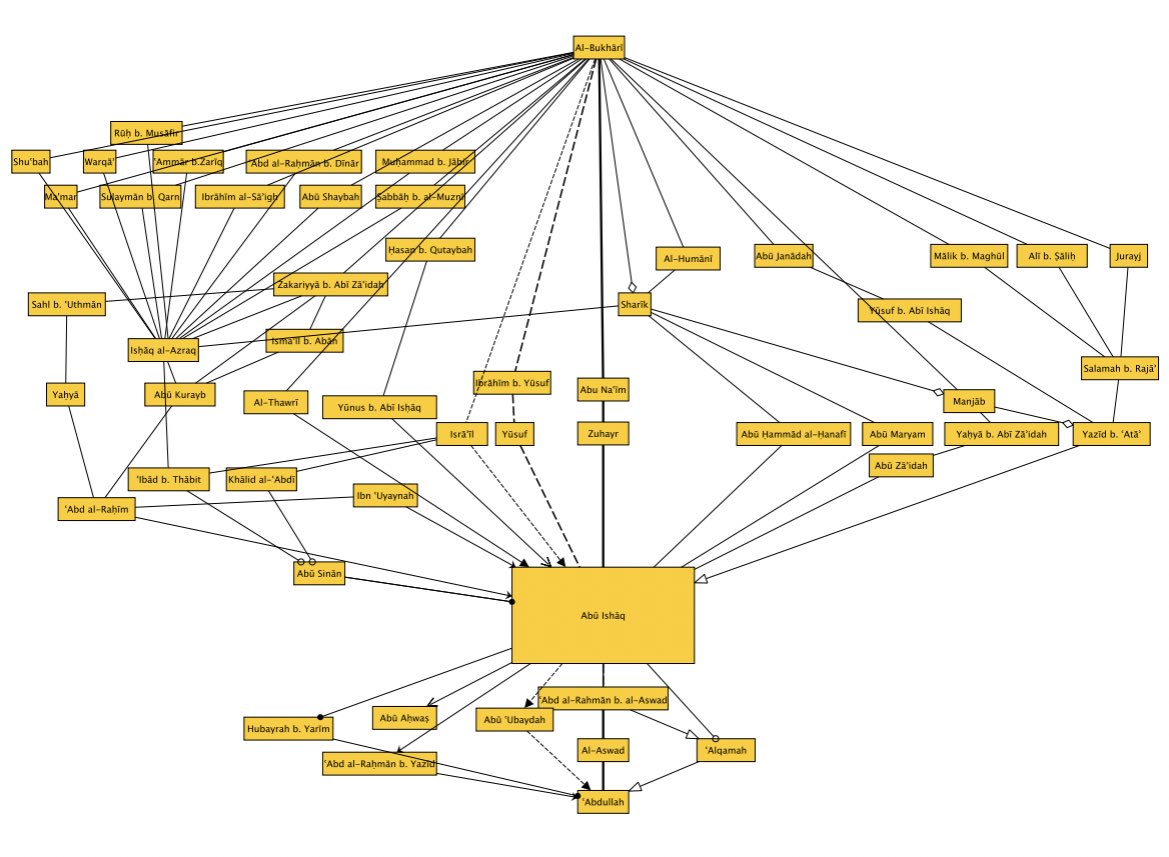

Here is a good illustration of what I mean when I say early Hadith critics were doing isnad-cum-matn analysis. A diagram I made a while ago from al-Daraqutni’s (d. 385) analysis of a hadith in Bukhari (may have some inaccuracies but the general idea is right). Look familiar?

After tracing all these chains (not relying on the books that survive till today), Daraqutni still holds the version given by al-Bukhari is the best. But he sounds a note of concern over the degree of differences being cited on the authority of Abu Ishaq, i.e. the common link.

Now consider that al-Bukhari, Muslim, Abu Hatim, etc, weren’t just engaging in this process for individual or at most isolated clusters of hadith. They assessed interlocking webs of the corroborations between narrators over thousands of isnads and their varying mutun.

Does that mean they were beyond the possibility of error? Of course not (and they never claimed such). But their huge intellectual contribution (which makes ICMA today even possible) should be better recognised in academic scholarship and its fruits not lightly dismissed.

Back to the diagram: this is based on the chains al-Daraqutni himself has through al-Bukhari. In other words, this is the scaffolding for each hadith that we don’t see when we read the Sahih. It is what is meant by picking the collection from 100,000s of hadiths (i.e. chains).

Bonus point: the middle chain with the black line is Bukhari’s version. In his Sahih he responds to the version with the dotted line through Abu Ubayda (recorded by Tirmidhi). He says: Abu Ubayda didn’t narrate it rather… (Abu Ubayda is the son of Abd Allah b. Mas’ud…

But was known to be too young to have received his father’s hadiths). So, al-Bukhari prefers the longer chain going through Ibn Mas’ud’s confirmed students. This shows how al-Bukhari is using other information to judge the credibility of the so-called single strands past the CL.

A clarification on the source of the isnads in the diagram.

https://twitter.com/ramoniharvey/status/1630856898265088000

Al-Daraqutni’s text for those wanting to check the accuracy of my diagram or dig further on this hadith.

https://twitter.com/ramoniharvey/status/1630858047261138946

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh