The registers of Canongate Kirk record on 17th Feb 1819 a 22 year old man was interred, having died 3 days earlier from fever. What they do not say is that he was far from the land of his birth and that he was a truly remarkable man. He was John Sakeouse and this is his story🧵👇

John was well known in Edinburgh and Leith, infact it was fair to say he was something of a celebrity, for he was a unique character in the port and in the city; he was a Kalaaleq , an Inuk from West Greenland, and was the first of his people to travel to Scotland.

He was born around 1797 in Disko Bay, west Greenland at a latitude of 69° N. We do not know his name in his native language, Danish missionaries had Christined him with the biblical names Johannes Zakaeus; John Sackhouse, or Saccheuse, but he signed himself Sakeouse)

From the missionaries he learned about the bible and had a knowledge Christianity. He also learned of the world beyond his horizon and picked up a little English. He developed a curiosity as to what was far over the horizon and he desired to learn about Christianity and art

Using his own initiative, in May or June of 1816 he took to his kayak and paddled out to a whaling ship that was getting ready to depart the Davis Strait. Using his English, he managed to convince the crew to help him stow away. John and his kayak were thus smuggled aboard.

Once safely over the horizon he announced his presence to the master; who either offered or threatened to turn around and put him ashore, but John was a persuasive communicator and the master, John Newton, was convinced to take him home with him

That ship was the "Thomas and Ann", it was owned by Peter Wood and Company of Leith, and that port was its destination. So that is how on the 15th August 1816, John Sakeouse came to Scotland, as a special passenger on the "Thomas and Ann", "with 11 fish".

On the journey back to Leith, he earned his passage by assisting the seamen. Standing 5' 6" tall, with a head of thick black hair, he was of stocky build and impressed his hosts with his great physical strength, his dexterity and also his gentle nature and eagerness to learn.

On arrival, news of his presence spread like wildfire around Leith. Crowds assembled, wanting to catch a glimpse of this unusual visitor. This prevented Newton from unloading his precious cargo of whale, so he had Sakeouse taken ashore and lodged in his house in the Timber Bush

The crowds followed and gathered outside Newton's house. John had never seen this many people in his life, but he hadn't come all this way just to hide away. So he took himself and his kayak down to the Wet Docks and with great showmanship put on an hour long display in it.

He thrilled the crowds by being able to roll his boat over at will, paddle it while inverted and roll it back upright again "in the twinkling of an eye". A ship's biscuit was floated on the water and from 30 yards he would hit it - and split it - with his harpoon.

His show was an instant hit, and it was put on each day for the crowds. Handbills were printed and money was collected. On Thursday 5th September, a grand race was organised; John against the best whaling boat and six of the best crew that Leith had to offer.

"A vast assemblage of persons of all ranks were collected at Leith. The piers, windows and roofs of houses and the decks and rigging of the vessels, were crowded with spectators; and the water from the harbour to near the Martello Tower was covered with boats."

Racing from the end of the pier, around the Martello Tower and back again; John was the clear winner, finding time to toy with the opposition but taking just 16 minutes.

An exhibition of his artefacts was put on in a dockside warehouse, described as"two sea unicorn's horns, the skulls of a sea horse and bear, the ear of a whale and the preserved skin of a black eagle". The money these ventures raised helped support him financially

By the end of August news of him had spread the length of the country; with newspapers not just in Scotland but London,all across England and in Belfast and in Dublin relating the story of "the Esquimaux* now at Leith".

* Esquimaux was the French term which was in written use at the time in the press for Inuit, it had yet to be anglicised to Eskimo. The Scottish whalers used the term "Yackie", and John described himself as "Yakee", a term he undoubtedly picked up from the whalers.

He lodged with the Newtons over winter and was taught English in "which he made considerable progress". He learned the flute and to dance. He sat for portraits, went to the theatre and was the toast of the soirées of Leith and Edinburgh, ingratiating himself with all who met him.

In spring 1817 the Leith whalers set out north again and John was with them on the "Thomas and Ann". Newton was under orders from his employer that John was to be "treated with the greatest kindness" and returned to where he had been picked up, unless he explicitly desired not to

On reaching his home however, John was distressed to find that his only living relative, his sister, had died over the winter. On learning that she had believed him dead and had died of a broken heart, he returned to Newton and made it known that he wished to stay with them

And so it was in September 1817 that once more the newspapers in Edinburgh reported that the "Thomas and Ann" was in Leith and once more it had a special passenger. And once again, this exciting news was reprinted from Inverness to London and from Cambridge to Belfast.

It was on a winter walk that John's adventures took an interesting new direction, for who should he by chance bump in to but one Alexander Nasmyth; pupil of Alan Ramsay and one of Scotland's foremost landscape and portrait painters at that time.

Nasmyth recognised John by his dress and was keen to make his acquaintance. He invited John up to Edinburgh to sit for a portrait and in return would give him drawing lessons.

Nasmyth got his painting, now in the National Galleries of Scotland, and John got the lessons that he had so desired. He proving to have a natural talent and be a quick learner. He came from a rich artistic culture and was the first Inuit to receive formal art training

It was through the well connected Nasmyth that John's life took its next turn; he was introduced to the naval explorer Captain Basil Hall and his father, Sir James, the President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The Halls were aware that the Admiralty was preparing an expedition to search for a Northwestern Passage, under fellow Scot Sir John Ross, and were quick to realise that having a native guide who could also act as a translator could prove invaluable to the mission.

The Halls wrote to Sir John Barrow, 2nd Secretary to the Admiralty, who agreed with them and asked for John to be sent to London if he was willing. Turning down offers of payment, John was keen to join the expedition so long as it was not just a ruse to send him back to Greenland

In London he as usual thrilled the crowds with kayaking and harpooning displays - in Deptford Docks. A trick that went down well was to throw his harpoon, which he could do with great accuracy over 50 yards, and then hit it with smaller "darts", time after time.

Captain Ross wasted no time in engaging John, however it nearly wasn't to be; in late March a stranger, who may have been an agent for the Aquatic Theatre, attempted to lure him away from and onto the stage, with offers of money and a considerable quantity of alcohol.

The usually sober John almost succumbed to temptation. But once through his hangover he thought better of it, apologised to Ross and stayed firmly on board and away from the dockside taverns thereafter. The Admiralty quietly ordered he be kept away from strangers thereafter.

Ross's expedition departed London on board a small fleet of hired Hull whaling ships on 18th April 1818. Ross led on his flagship "Isabella", with Lieutenant Parry on the "Alexander" and the ill-fated Lieutenant Franklin on the "Trent".

Their search was for the Northwest Passage and the Bering Strait beyond, and part of the expedition intended to strike out for the North Pole. Their journey would find none of those destinations, but would take them further north than any British navigator had yet been.

The convoy arrived off Greenland in June. By the end of the month, they reached 70° N - Disko Bay, the land where John - or Jack as the sailors had taken to calling him - had been born. John took take to his kayak, returning with specimens of birds for the expedition's scientists

Another time he returned with a party of local Inuit. Acting as a translator, he negotiated for them to return with the gift of a dog sled for Ross. They were invited aboard for coffee and biscuits and shown around, had their portraits taken and further gifts were exchanged.

An impromptu cèilidh was then held on the deck, with the Inuit dancing Scottish Reels with the seamen (most of whom were Scots) to the music of their fiddler. Ross describes John as acting as the "master of ceremonies", calling out the dances.

Catching the attention of a young Inuit woman, "the best looking of the group", John was given a lady's shawl by one of the officers to present to her. She returned his affections with the gift of a ring. Ross was in "no possible doubt [he] had made an impression on her heart".

The guests departed and John escorted them home to perhaps return with more specimens. It was at this point however that he suffered an unfortunate accident; demonstrating a gun to the Inuit, he over-filled it under an assumption he described as "plenty powder, plenty kill.

Letting the weapon off, he could not handle the recoil and broke his collar bone. A search party had to be sent out to retrieve him when he did not return to the ships before they departed.

They continued north into Baffin Bay, making an anti-clockwise navigation in search of the North West Passage. Ross made an illustration of his flotilla as it moved carefully through the ice at 70°44' North.

At 75°25' N they reached a bay the Greenlanders call "Qimusseriarsuaq". Ross Christened it in English as Melville Bay, after Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty who had given Ross his first commission (for whom Melville Street in Edinburgh is named).

By August they got as far north as 75°55', before becoming trapped in the ice and could go no further. It was with a great deal of skill, hard work and luck that they were able to extricate the Isabella and the Alexander, and now headed west around the top of Baffin Bay.

Soon they were heading south and on August 9th 1818, they came to what Ross called Prince Regent Inlet. Here, at 75°55' North, 65°32' West, and with the unique help of John Sakeouse, they made first contact with what Ross called the "Arctic Highlanders": the native Inughuit.

It was the Inughuit who spotted them first. When Ross's lookouts spotted them in return, they took these men far out on the ice to be stranded whalers, and made for them. As they approached, they realised that they were natives travelling on dog sledges.

When they came within shouting distance, John attempted to call to them in his language, but the men took to their sleds and fled. Boats were sent out and some gifts left on the ice for them.

Ross had the men make a large flag showing the image of the sun and the moon, with an outstretched hand holding a spring of a native shrub in the manner of an olive branch (this western metaphor would of course have been completely lost on them.)

The flag was run up a pole in a prominent position on the ice, to which was also affixed a bag of gifts and a large outline of a hand pointing to the ships.

The next morning the men returned with 8 sleds, stopping on the ice a mile short of the ships. The flagpole enticed the men and their sleds closer, but they remained cautiously 300 yards distant, apparently in conversation. It was at this point that John stepped in.

Taking a bag of gifts, and a white flag (another hopeless symbol for communicating with people who had never encountered white men before), John strode out on the ice. Dressed in the garb of a western sailor, they had no idea who he was, or what his act of removing his hat meant

As he approached they pulled a knife on him, implored him to be on his way and made it clear that they could kill him if needs be. In return, the ever placid John offered them a British-made knife, tossing it to them. On examining it, the men were impressed and pulled their noses

Recognising a sign of friendship, John pulled his nose too, and a rapport was formed. He presented them with a string of beads and showed them a chequered shirt. This was not just the first time the Inughuit had met white men, it was their first exposure to a western Greenlander

John had a familiarity with their dialect from an old woman who had once nursed him, and was able slowly able to communicate. Using his natural talents and the tuition in from Alexander Nasmyth, John painted a picture to capture this scene, presenting it to Captain Ross

John, wearing a blue jacket and beaver hat, with his arm held in a sling, is seen holding the shirt while two Inughuit inspect the gift of a mirrors with incredulity.. In the foreground, Ross and Parry offer other gifts, receiving narwhal tusks in return.

The Inughuit had never before seen a ship; they were not seafaring people, had never seen a kayak and had no word for it, living entirely on the land and using dog sleds for travel and hunting.

So it was with some difficulty that they were eventually enticed aboard onto these winged "Islands of Wood" (they had never before seen a shrub with a trunk wider than your finger, so the ships timbers were an incredible sight for them).

The men were given a tour of the ship, before being convinced to sit in chairs (something they had never seen and whose purpose they did not understand) to have portraits taken. They were offered biscuit, salt beef, plum pudding and Aquavit, all of which they thoroughly disliked.

With John acting as interpreter, they were able to learn that the Inughuit did not count beyond ten, their knives were fashioned from iron extracted from a rock in the mountains, that they lived in family units by a form of mutual agreement between the" husband" and "wife"

They had sent their women and children into the mountains to safety; the menfolk had come forth only to ask the interlopers to leave. They had a chief - Tulloowah - to whom other families gave a tribute. They had no organised religion, but each family had a "sorcerer"

They had no concepts of weapons or war, or of lands and people beyond their own. They assumed the white-faced Europeans must be some sort of ghost whose ships had flown down from the air. Before leaving, they were presented with gifts of planks of wood that they had had desired

The Inughuit returned a few days later. This was a different party and had come forth after seeing the gifts that the first had returned with and having received assurances that the "Islands of Wood" and their ghostly residents were not an immediate threat.

More gifts were exchanged, and the leader of the party helped himself to Ross's telescope, shaving razor and a pair of scissors, which Ross was pleased to overlook. Before their final departure, Ross gave them a portrait of the Prince Regent as a present for "their king"

Ross now moved further south and west, coming to Lancaster Sound at 74°19½' N 78°33' W at the end of August where he took a fateful decision...

Imagining he could see distant mountains (they were a mirage) he was convinced there was no way through and turned around against the wishes of his subordinates. So convinced was he, he named the mountains the Croker Range and made a detailed landscape illustration of them.

Abandoning the primary mission of the North West Passage, Ross now headed south along the western edge of Baffin Bay, occupying the expedition with scientific collection and experimentation rather than exploration.

By the end of September they were at Resolution Island, at 61°30' N, well out of the Arctic Circle, and Ross decided to end operations for the season and head for home. A month later, on October 29th, they sighted Foula, the westernmost island of the Shetland Archipelago.

On November 14th they dropped anchor for the last time, in Grimsby Roads, and Ross set off at once for London and their Lordships of the Admiralty with his logs, journals, charts and letters. Unfortunately he did not find the hero's welcome that he might have expected.

His subordinates, particularly Parry, challenged his decision to turn around in Lancaster Sound. Seeds of doubt were sown in The Admiralty that Ross was not to be trusted, and they organised an expedition for the following year, led by Parry, and on which Ross was not invited.

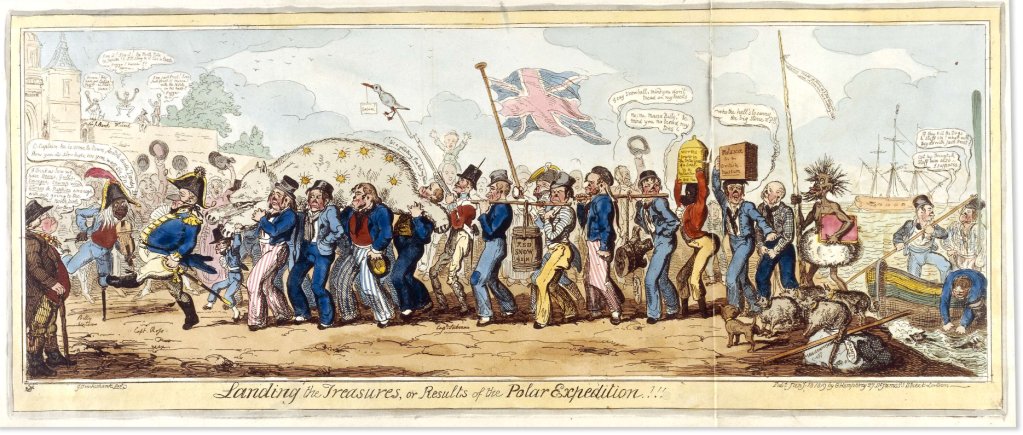

The press lampooned him, a scathing satirical cartoon showing him pompously leading his crew, mutilated by frosbite, carrying back nothing but specimens of animals and rocks. The implication was clear; Ross was a failure: his results and collections were worthless

The satirist did not treat John with the respect and credit he merited. He portrayed him as a deeply racist stereotype, a savage called "Jack Frost" in a fur skirt, clutching an album of his drawings. The sailors suggest he should have his throat cut and be stuffed also.

John did not linger in London, and asked to be returned to his friends in Leith. Parry - although contemptuous of Ross - recognised the importance of John and arranged that he should be included again in the 1819 expedition.

Unfortunately this was never to be. John took ill at the start of 1819 with "a violent inflammation in the chest". John Newton, the whaling master who had first been convinced to bring John to Leith, and his family nursed John through his illness

At first he seemed to improve, and despite doctor's orders to the contrary - soon felt well enough to venture out in the search of fish, which he brought back to his lodgings to cook for himself.

A few days later, he relapsed. He told his companions his late sister had called to him from a dream, and he knew he was dying. Calling for his Catechism, he held it "till his strength and sight failed him, when the book dropped from his grasp, and he shortly afterwards expired".

All of Leith mourned his loss, and a respectful funeral was arranged in the Canongate and paid for by his friends. "He was followed... by a numerous company, among whom were not only his old friends and patrons from Leith, but many gentlemen of high respectability in this city".

His final resting place is not marked, but was given as "in the area 8 feet south of Fraser's ground and 4 feet from the north walk". His possessions, including his sealskin clothing, were left to Captain Ross, who donated them to the Museum of the University of Edinburgh.

You can read this whole thread as a single blog post over at @threadinburger 🔗👉threadinburgh.scot/2023/03/04/the…

I have emailed the Canongate Kirk to find out if they have any other information that might clarify more precisely where John's final resting place is. Given it is unmarked, I've also enquired about the possibility of having some sort of small marker on or near the spot.

Thread broke! Continues here:

https://twitter.com/cocteautriplets/status/1632053491836362752?t=mebKXrNFe19oWtv5znB6DQ&s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh