The Norwegian Healthcare Investigation Board, (NHIB/UKOM) has deemed puberty blockers, cross-sex-hormones & surgery for children & young people experimental, determining that the current “gender-affirmative” guidelines are not evidence-based and must be revised. /1

The UKOM report asserts that future guidelines must rely on a systematic review of evidence rather than cherry-picking studies, and that all hormonal and surgical interventions must be restricted to research settings to ensure clear protocols, safeguarding & adequate follow-up./2

The existing Norwegian treatment guidelines for gender-dysphoric youth, based on a 2015 report ”The Right to the Right Sex,” closely mirror WPATH SOC7 “gender-affirming” model. Medical gender affirmation is widely available to youth, with no psychological assessments required. /3

Under the current Norwegian guidelines, youth may receive puberty blockers at tanner stage 2, cross-sex-hormones at 16, and surgeries at 18. The report noted that these widely available interventions are irreversible, carry many risks, and rest on insufficient evidence. /4

The report criticized Norway’s current "gender-affirmative" guidelines as inadequate, noting a lack of specificity regarding assessment & determination of medical necessity of risky and irreversible interventions provided to youth whose identities are still forming. /5

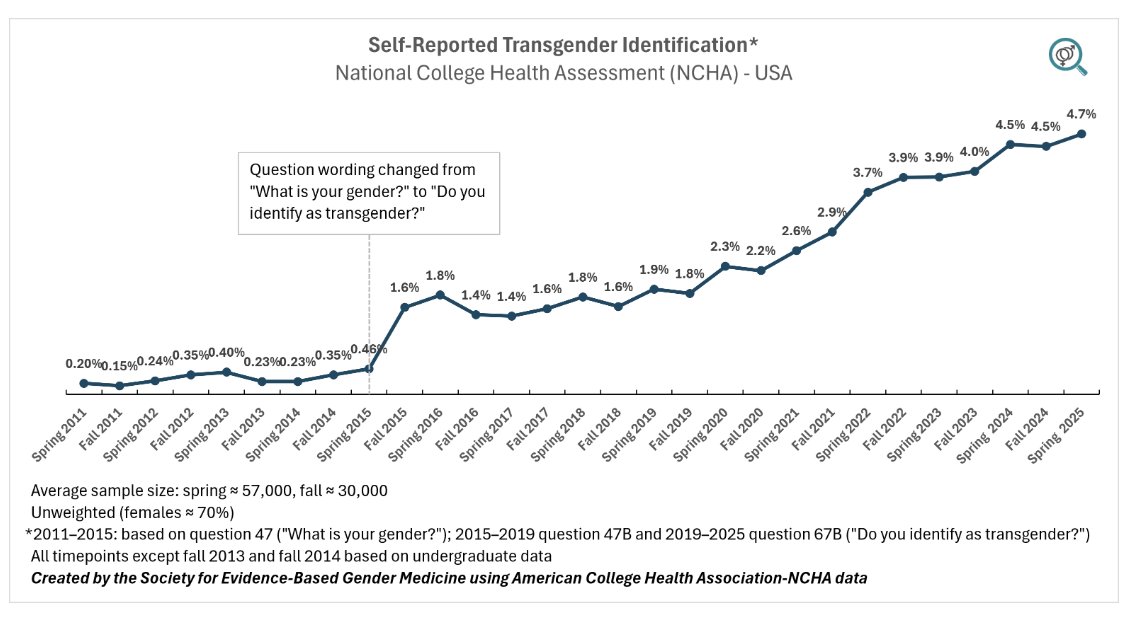

The Norwegian Healthcare Investigation Board noted several worrying trends: the rapid rise of gender dysphoria in adolescents (esp. females), the high burden of mental illness (75%) & a high prevalence of neurocognitive conditions (ADHD/autism, Tourette) in the affected youth. /6

The recommendations by the Norwegian Healthcare Investigation Board (NHIB/UKOM) align Norway with the changes among the growing number of European countries (Sweden, Finland, England) which aim to safeguard youth from harm by sharply restricting youth gender transitions. /7

However, unlike Sweden, Finland and England, Norway explicitly calls out the group of young adults whose development is still ongoing and who are at risk for erroneously undertaking gender transitions. The report notes that the age of consent for sterilization in Norway is 25./8

NHIB/UKOM notes that the right to medical care does not include the right to experimental treatments. As an experimental intervention, gender transitions will be subject to heightened scrutiny around informed consent, eligibility criteria, and outcomes evaluation./9

Norway's proposed model appears to resemble the model of care outlined in the Cass review. Gender dysphoric youth will receive care for their distress in local primary care settings with multidisciplinary support. Youth gender transitions will be an exception, not the rule. /10

The Board also comments on the highly polarized & unbalanced nature of the discussions surrounding care for gender-dysphoric youth, which stifles scientific debate. The Board calls on all parties to treat each other with professionalism, empathy and respect. /11

SEGM will be analyzing the report in more detail. Currently, our assessment is that the UKOM report is akin to UK's Cass Review in that it makes recommendations for restructuring youth gender services. How Norway's NHS will implement these recommendations remains to be seen. /12

The largest Norwegian daily newspaper, Aftenposten, interviewed the UKOM project leader, Stine Marit Moen. The links to the interview, the executive summary, and the full report are are provided below. /13

aftenposten.no/norge/i/jlwl19…

ukom.no/rapporter/pasi…

https://t.co/3gWmdKZTHQ

aftenposten.no/norge/i/jlwl19…

ukom.no/rapporter/pasi…

https://t.co/3gWmdKZTHQ

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh