Today is my last day in a university position so I wanted to write a few things about #leavingacademia⬇️

On NLP, Computational Linguistics and Meaning. Above all: on loving your object of study and owning it. \1

On NLP, Computational Linguistics and Meaning. Above all: on loving your object of study and owning it. \1

I don't often post here. I’m not a great talker. Which is a real shame because my research field loves talking on social media. About big engineering feats, conference acceptance rates, one's own success or struggles. Although, I note, relatively little about language itself. \2

At the risk of sounding sentimental, I became a computational semanticist because I cared about meaning. Deeply. I wanted to know what it was, the same way others want to know about beetles, asteroids or gravitation. I wanted to do science. \3

Science is the human activity that seeks to explain and predict natural phenomena. It presupposes that you spend a lot of time observing your object of study. That you befriend it. That you handle it with great care, lest your touch might affect its natural properties. \4

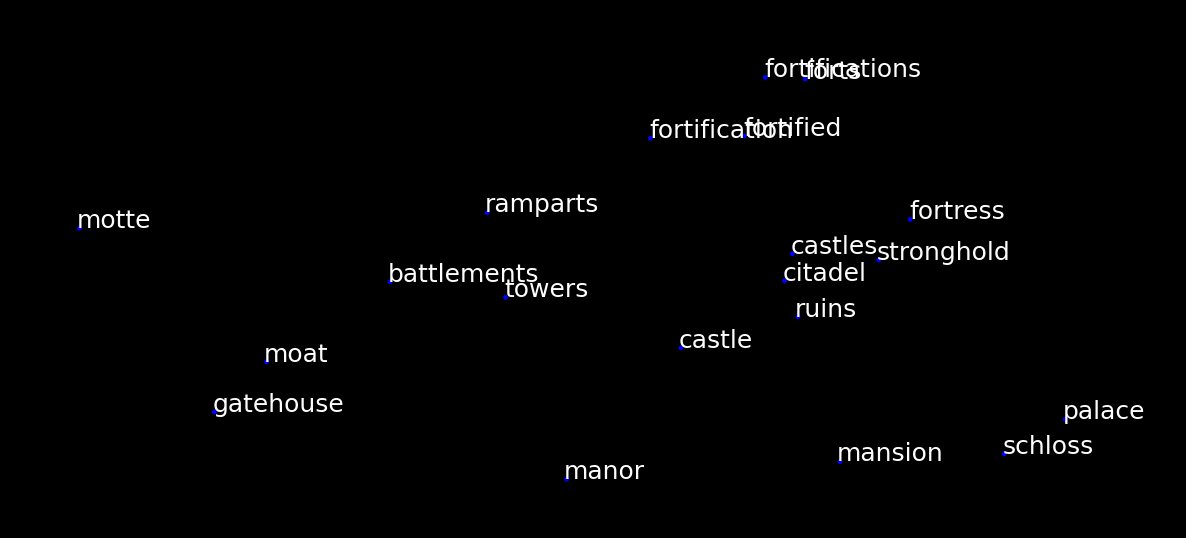

Language is a phenomenon which can be investigated with computational models in myriads of ways. But again, it must be handled with care. You can't 'put language into a machine' any more than you can put a beetle in a machine (it will break your GPU *and* the beetle). \5

It seems we were unhappy about how long it took to pin language down. So we found that we could instead fake it. The engineering side of our field now loves building beetle-robots with a UTF-8 carapace. Which is fine by me. (As long as you call a robot a robot.) \6

While engineers play, the rest of us are presumably doing the science. The actual beetles. The actual language. Taking our time and appreciating that our questions will not be solved in this lifetime, but that we will have been as close to them as one can be... Not quite. \7

We instead spend time dismantling the metal beetle (which we perfectly know is not a real beetle), trying to find its heart. Is this a thorax? An antenna? No. But there must be *something* to be found because no scientist would study something that is not there. Right? \8

Like others, I had times of bitterness about all this. But it always disappeared when I allowed myself to daydream away from the buzz, when I felt I had some private time with language again. So I started to think that academia itself did not matter so much. And here we are. \9

Doubling up on sentimentality: I do not want to lose the relationship I have built to language and meaning over the years, and I feel remaining in my field is somehow damaging to that relationship. I guess Semantics and I need some time away. \10

There are many paths to being a scientist. But competing for attention and high rankings is not one of them. Language does not care about your H-index or the size of your LLM. It shouldn't be about us, it should be about *it*. \11

I suppose some people will ask 'what I am going to do now'🙂

I am going to do what I’ve always done. Spend some time with meaning. Tinker with single boards. Go find some beetles 🪲 \the end

I am going to do what I’ve always done. Spend some time with meaning. Tinker with single boards. Go find some beetles 🪲 \the end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh