My last @NotionHQ template launch made $88,421 in its first 30 days.

This came entirely from two emails sent to a waiting list of 3,201 people.

Here are the exact subject lines, email copy, and all other details:

This came entirely from two emails sent to a waiting list of 3,201 people.

Here are the exact subject lines, email copy, and all other details:

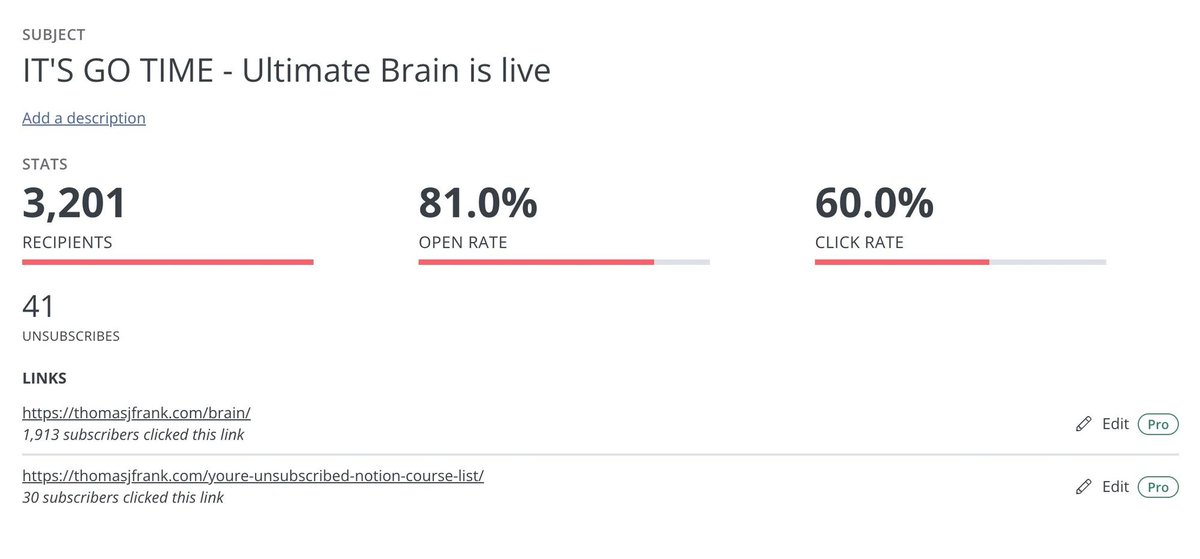

Subject Line:

"IT'S GO TIME - Ultimate Brain is live"

- 3,201 recipents

- 81% open rate

- 60% click rate (1,913 clicks)

(I use @ConvertKit for my email marketing)

"IT'S GO TIME - Ultimate Brain is live"

- 3,201 recipents

- 81% open rate

- 60% click rate (1,913 clicks)

(I use @ConvertKit for my email marketing)

@ConvertKit Credit where credit is due:

I stole this subject line whole-cloth from @fortelabs

The lesson I took from his experience and mine:

If you have an excited, captive audience, don't overthink the subject line.

Go short, punchy, and exciting.

I stole this subject line whole-cloth from @fortelabs

The lesson I took from his experience and mine:

If you have an excited, captive audience, don't overthink the subject line.

Go short, punchy, and exciting.

https://twitter.com/1909232666/status/1504139039573626880

Email body copy:

Some highlights:

- 3 sales page links

- Short list of features

- Launch discount

$99 launch price with a 50% discount code, so most people paid $49.

You can also read the email archive itself here: ckarchive.com/b/zlughnhgm77v

Some highlights:

- 3 sales page links

- Short list of features

- Launch discount

$99 launch price with a 50% discount code, so most people paid $49.

You can also read the email archive itself here: ckarchive.com/b/zlughnhgm77v

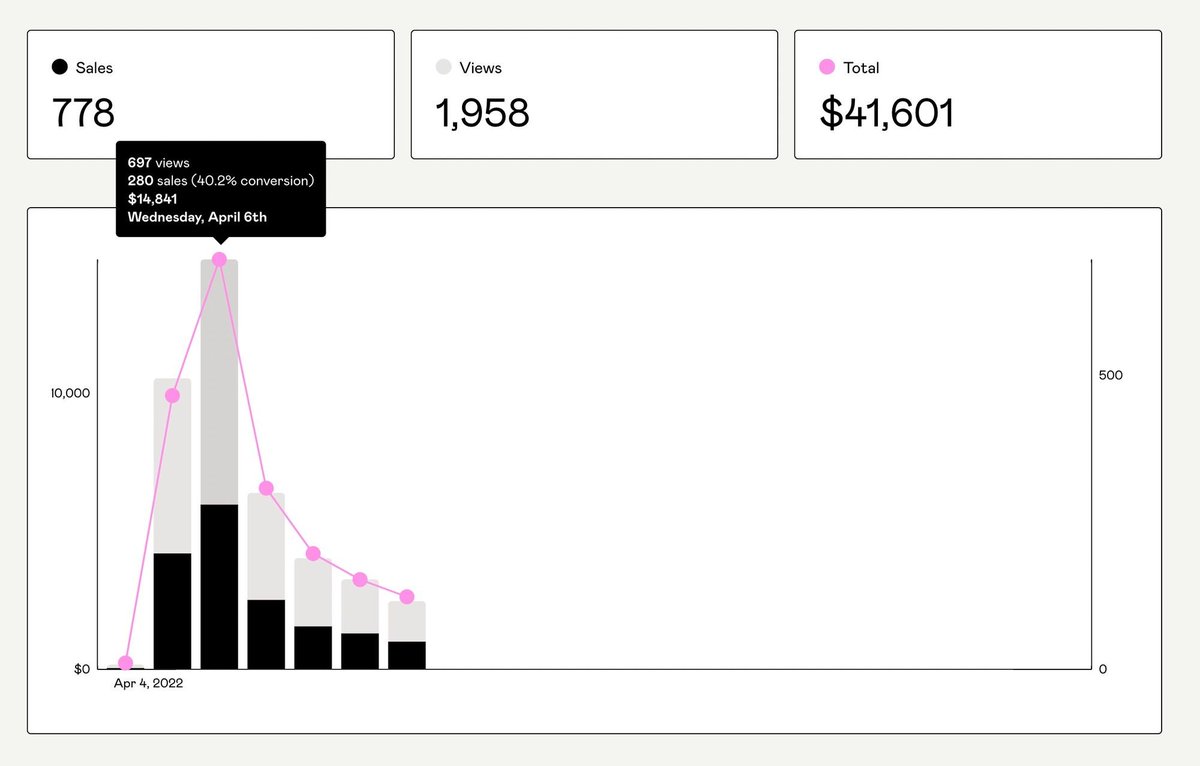

Here are the sales results from the first week.

I sent the email at 6:55pm (Mountain Time), so Day #2 ended up being the peak of the launch.

- Day 1: $9,910

- Day 2: $14,841

- Day 3: $6,558

I sent the email at 6:55pm (Mountain Time), so Day #2 ended up being the peak of the launch.

- Day 1: $9,910

- Day 2: $14,841

- Day 3: $6,558

Two days later, I used @ConvertKit's "Send to Unopens" feature to re-send the email to everyone who didn't open the first one.

Subject line: "Second Brain Notion Template"

This brought in an additional 184 clicks to the sales page.

(IMO: Use this feature sparingly)

Subject line: "Second Brain Notion Template"

This brought in an additional 184 clicks to the sales page.

(IMO: Use this feature sparingly)

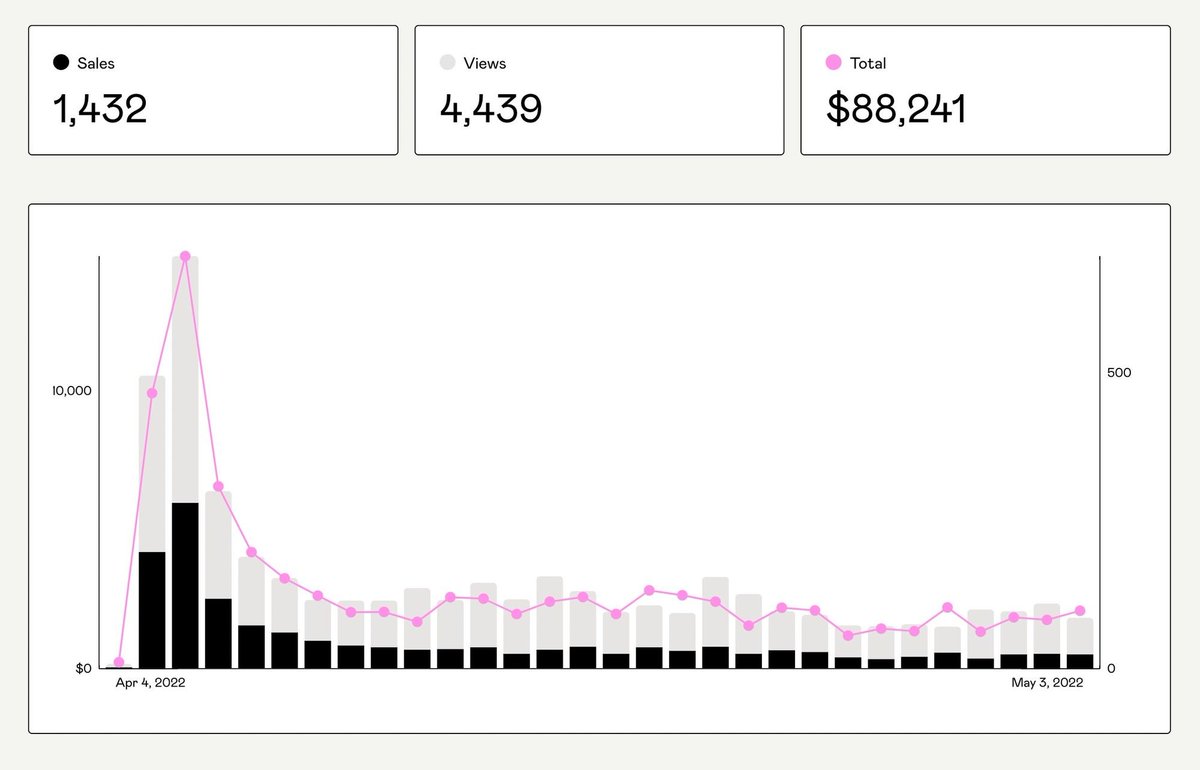

Here are the sales results for the full 30 days after this initial launch:

- 1,432 sales

- $88,241 in revenue

On the 31st day, I sent a new launch email to my full list (35,000 at the time), so this period is the best look at the impact of the initial waitlist launch.

- 1,432 sales

- $88,241 in revenue

On the 31st day, I sent a new launch email to my full list (35,000 at the time), so this period is the best look at the impact of the initial waitlist launch.

The sales page looked very similar to how it still does today.

Here's a breakdown of some of the features and decisions that went into it:

Here's a breakdown of some of the features and decisions that went into it:

https://twitter.com/39262778/status/1523731047589900288

How did I build the waitlist?

I'll cover this more deeply in a future thread, but the gist is:

I linked the waitlist's landing page in a synced header block on all my free templates.

I also teased it in one video on Thomas Frank Explains (my Notion-focused YouTube channel)

I'll cover this more deeply in a future thread, but the gist is:

I linked the waitlist's landing page in a synced header block on all my free templates.

I also teased it in one video on Thomas Frank Explains (my Notion-focused YouTube channel)

My main marketing funnel is pretty simple:

1. Make great @NotionHQ tutorials

2. Use them to promote free templates

3. Ask people to sign up for newsletter when they're getting a free template

4. Gently promote paid templates at the top of free templates

1. Make great @NotionHQ tutorials

2. Use them to promote free templates

3. Ask people to sign up for newsletter when they're getting a free template

4. Gently promote paid templates at the top of free templates

If you'd like to study my sales page – or if you want the best productivity system for Notion – you'll find it here:

thomasjfrank.com/brain/

I recently bought a landing page roast for this page, so I'll share the updates I make to it soon.

Follow me if you want to see them!

thomasjfrank.com/brain/

I recently bought a landing page roast for this page, so I'll share the updates I make to it soon.

Follow me if you want to see them!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh