"One of the greatest Wall Street coups":

Gibson Greetings, Inc.

In January 1982, Bill Simon bought 33% of Gibson for $330K. The value of that $330K investment when Gibson went public in May 1983: $66.7 million.

That's a 202X return in 17 months.

Here's how he did it…

Gibson Greetings, Inc.

In January 1982, Bill Simon bought 33% of Gibson for $330K. The value of that $330K investment when Gibson went public in May 1983: $66.7 million.

That's a 202X return in 17 months.

Here's how he did it…

Bill Simon, a trader-turned-statesman, left his job as Treasury Secretary in 1977.

His financial position:

- Salary: $66 thousand

- Net Worth: $2.5 million

He spent the next five years:

- Consulting

- Value investing

- Commodity trading

Then he found his niche: LBOs

His financial position:

- Salary: $66 thousand

- Net Worth: $2.5 million

He spent the next five years:

- Consulting

- Value investing

- Commodity trading

Then he found his niche: LBOs

In 1981, Bill Simon and Ray Chambers, an accountant-turned-investor, formed Wesray. The plan: Use Simon's contacts and Chambers's analytical skills to buy good companies with borrowed money.

Wesray's first buyout? Gibson Greetings

Wesray's first buyout? Gibson Greetings

Why buy Gibson?

Gibson, the third-largest maker of gift cards and wrapping paper, had qualities Wesray liked:

- Low-tech business

- Low-price, high-value product

- Non-cyclical demand

These qualities produced:

- HSD sales growth (w/o a decline)

- Low-thirties ROICs

Gibson, the third-largest maker of gift cards and wrapping paper, had qualities Wesray liked:

- Low-tech business

- Low-price, high-value product

- Non-cyclical demand

These qualities produced:

- HSD sales growth (w/o a decline)

- Low-thirties ROICs

Another reason to buy Gibson: Valuation

Wesray paid $84.6M for:

- $28.0M LTM EBIT

- $39.2M NTM EBIT

EV/EBIT Multiples:

- Trailing: 3.0x

- Forward: 2.2x

Why the low price? Two reasons:

- Macro

- Forced seller

Wesray paid $84.6M for:

- $28.0M LTM EBIT

- $39.2M NTM EBIT

EV/EBIT Multiples:

- Trailing: 3.0x

- Forward: 2.2x

Why the low price? Two reasons:

- Macro

- Forced seller

MACRO

Wesray bought Gibson when:

- The US was in a recession

- Interest rates hit 15%

- Inflation exceeded 10%

Simon: "When we bought Gibson, all the market conditions were wrong. Interest rates were too high. Inflation was too high. But that's when bargains exist."

Wesray bought Gibson when:

- The US was in a recession

- Interest rates hit 15%

- Inflation exceeded 10%

Simon: "When we bought Gibson, all the market conditions were wrong. Interest rates were too high. Inflation was too high. But that's when bargains exist."

FORCED SELLER

Wesray bought Gibson in a carveout from RCA. At time of sale, RCA's "mountain of debt and disappearing profits left it so starved for cash that its new chairman was trying to sell off important hunks of its business."

The result: Gibson's firesale for $84.6M

Wesray bought Gibson in a carveout from RCA. At time of sale, RCA's "mountain of debt and disappearing profits left it so starved for cash that its new chairman was trying to sell off important hunks of its business."

The result: Gibson's firesale for $84.6M

Where'd Wesray get the $84.6M?

DEBT = $83.6M

- $39.8M revolver

- $13.0M term loan

- $30.8M sale-leaseback

EQUITY = $1.0M

- Simon: $330K

- Chambers: $330K

- Management: $200K

- Other: $140K

Think that's too much debt? It wasn't.

DEBT = $83.6M

- $39.8M revolver

- $13.0M term loan

- $30.8M sale-leaseback

EQUITY = $1.0M

- Simon: $330K

- Chambers: $330K

- Management: $200K

- Other: $140K

Think that's too much debt? It wasn't.

Gibson had…

Equal-to-better credit metrics

…Compared to today's LBOs.

DEBT/EBIT

- Gibson: 2.1x (2.9x at peak)

- LBO: 3x - 6x

EBIT/INTEREST

- Gibson: 2.0x (including rent)

- LBO: 2x - 5x

Gibson also had more upside.

Equal-to-better credit metrics

…Compared to today's LBOs.

DEBT/EBIT

- Gibson: 2.1x (2.9x at peak)

- LBO: 3x - 6x

EBIT/INTEREST

- Gibson: 2.0x (including rent)

- LBO: 2x - 5x

Gibson also had more upside.

Why more upside?

Compare the LTVs:

- Gibson: 98.8%

- LBO: 80% (or less)

High LTVs mean that (a) small changes in profits and multiples produce (b) outsized changes in equity value.

This is all it'd take for Gibson to 100X:

- 30% EBIT growth

- 2 turns multiple expansion

Compare the LTVs:

- Gibson: 98.8%

- LBO: 80% (or less)

High LTVs mean that (a) small changes in profits and multiples produce (b) outsized changes in equity value.

This is all it'd take for Gibson to 100X:

- 30% EBIT growth

- 2 turns multiple expansion

How'd Gibson actually do?

Results over Wesray's 17-month hold:

- 40% EBIT growth

- 4.7 turns multiple expansion

After adjusting for…

- Changes in debt

- Share issuances

…Gibson produced a 193x return.

Wesray's dollar gain: $192.5M on $1M

Results over Wesray's 17-month hold:

- 40% EBIT growth

- 4.7 turns multiple expansion

After adjusting for…

- Changes in debt

- Share issuances

…Gibson produced a 193x return.

Wesray's dollar gain: $192.5M on $1M

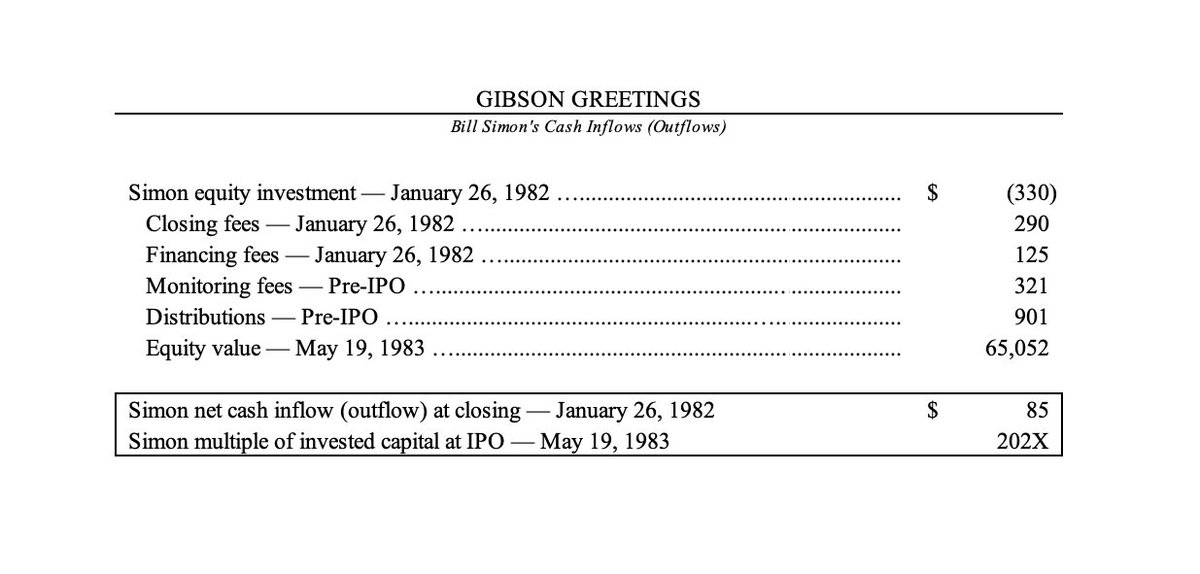

Simon did even better.

On closing day, Simon paid himself:

- Deal fees: $290K

- Financing fees: $125k

His net investment: - $85K

He also received…

- $321K consulting fees

- $901K distributions

…In the first 17 months.

Simon's dollar gain: $66.7M on $330K

On closing day, Simon paid himself:

- Deal fees: $290K

- Financing fees: $125k

His net investment: - $85K

He also received…

- $321K consulting fees

- $901K distributions

…In the first 17 months.

Simon's dollar gain: $66.7M on $330K

Simon made more on the deal than Lehman Brothers, Gibson's investment bankers, made in a year. It was so good that Steve Schwarzman, the Lehman banker overseeing Gibson's sale, and Pete Peterson, Lehman's CEO, quit and started their own LBO firm.

That firm: Blackstone

That firm: Blackstone

Simon's biggest deal risk? Closing

Gift card and wrapping paper seasonality required large working capital investment:

- Receivables: 6 to 11 months

- Inventories: 3 to 9 months

To fund the WC swings, Gibson needed a $100M credit line, which exceeded the $84.6M purchase price.

Gift card and wrapping paper seasonality required large working capital investment:

- Receivables: 6 to 11 months

- Inventories: 3 to 9 months

To fund the WC swings, Gibson needed a $100M credit line, which exceeded the $84.6M purchase price.

The solution? A sale-leaseback.

Wesray arranged a $30.6M sale-leaseback of Gibson's real estate. This enabled Wesray to fund the $84.6M LBO and still have $60.2M of drawdown left for seasonal working capital needs.

+ $84.6M cash for LBO

+ $60.2M undrawn

= $144.8M total funding

Wesray arranged a $30.6M sale-leaseback of Gibson's real estate. This enabled Wesray to fund the $84.6M LBO and still have $60.2M of drawdown left for seasonal working capital needs.

+ $84.6M cash for LBO

+ $60.2M undrawn

= $144.8M total funding

Want to learn more about Simon? Check out his autobiography. It includes background on both his government service and his investing career.

amazon.com/Time-Reflectio…

amazon.com/Time-Reflectio…

APPENDIX

More reasons Gibson was cheap: RCA Insider

Julius Koppelman, "the RCA exec handling the sale," brought Gibson to Wesray. He also "wasn't interested in getting the highest price." And "when the deal closed, Koppelman left RCA to become a consultant for Wesray."

More reasons Gibson was cheap: RCA Insider

Julius Koppelman, "the RCA exec handling the sale," brought Gibson to Wesray. He also "wasn't interested in getting the highest price." And "when the deal closed, Koppelman left RCA to become a consultant for Wesray."

APPENDIX

Bill Simon on patience:

"Patience is the hardest thing in the world for an investor. Just to sit there, it's hard to do nothing."

Bill Simon on patience:

"Patience is the hardest thing in the world for an investor. Just to sit there, it's hard to do nothing."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh