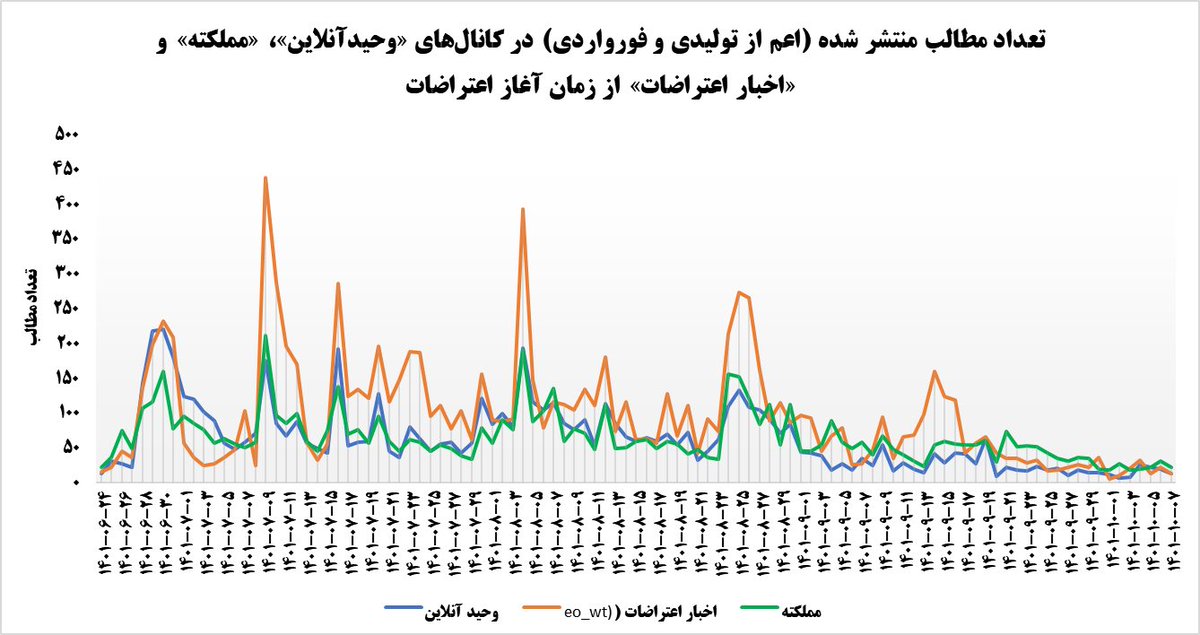

1. Despite Iran’s history of mass movements and widespread anger, the #WomanLifeFreedom protests remained small and sporadic and have now subsided.

In @ForeignAffairs, I explain that ordinary Iranians need economic resources to exercise their political power.

The West can help.

In @ForeignAffairs, I explain that ordinary Iranians need economic resources to exercise their political power.

The West can help.

2. The protests triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini felt different from the outset. They were led by women and political in their aims. They generated solidarity across class and regional lines. It seemed like the protests could snowball, despite the state’s violent response.

3. But that didn’t happen.

The first stumbling block was the failure to organise strikes among the working class. Labor activists tried for months to get local and national strikes off the ground with little success. Something was holding workers back.

The first stumbling block was the failure to organise strikes among the working class. Labor activists tried for months to get local and national strikes off the ground with little success. Something was holding workers back.

4. The middle class, likewise, didn’t engage at the scale seen in previous movements with an overt political focus, such as the 2009 Green Movement. Protests had a sporadic, even spontaneous quality. We didn’t see the kinds of mass mobilisations that truly put pressure on elites.

5. As I write in the essay, acknowledging the limited scale of the protests does not discredit the efforts of organizers and activists in Iran. On the contrary, anyone who cares about fundamental political change in the country *needs to understand* why the protests faltered.

6. There is a robust debate about what makes social movements succeed. It takes a lot of things. But among the most important conditions is the availability of resources—time, money, effort.

People need to be in a position to devote these things to the movement.

People need to be in a position to devote these things to the movement.

7. This is where Western sanctions policy matters. Iran is a poorer country than a decade ago, owing to sanctions. Household consumption has declined 20% since 2010. The poverty rate as risen 10 pp. Iranians are undeniably in the most economically precarious position in decades.

8. In recent meetings with US and European officials, I’ve asked an uncomfortable set of questions. Do they assess that the sanctions have reduced the political power of ordinary Iranians? Has the capacity for mobilization among citizens diminished.

9. The answers were concerning in two respects.

First, there doesn’t appear to be any systematic effort to assess such outcomes right now.

Second, everyone I spoke to agreed that it was plausible that sanctions could have had this effect.

First, there doesn’t appear to be any systematic effort to assess such outcomes right now.

Second, everyone I spoke to agreed that it was plausible that sanctions could have had this effect.

10. Let’s be clear. The sanctions are going to remain in place. Iran is engaging in repression at home, selling drones to Russia, and continuing nuclear escalation. I am not calling for any substantive sanctions relief. Policymakers will obviously keep applying sanctions for now.

11. For this reason, activists, especially those in the diaspora, are wasting energy simply calling for more sanctions.

To account for the connections between economic means and political might, we need to move away from the mindset of maximising pressure and think critically.

To account for the connections between economic means and political might, we need to move away from the mindset of maximising pressure and think critically.

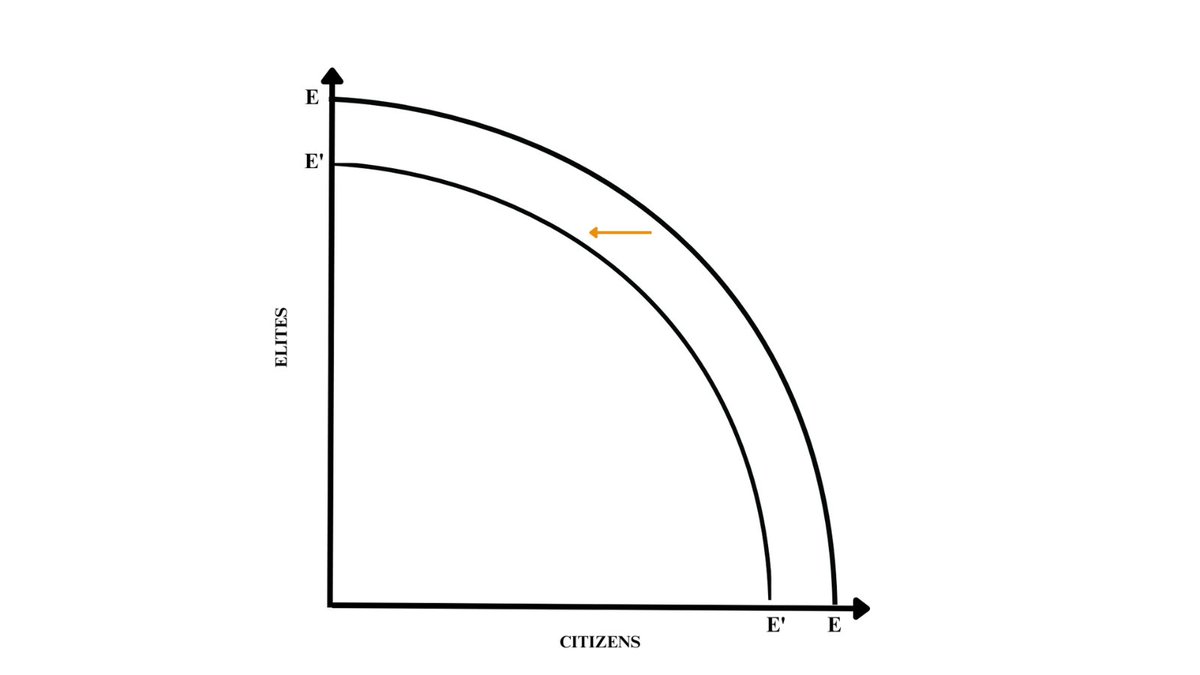

12. In the essay, I offer three concrete ideas to help restore political power to ordinary Iranians by reducing their economic precarity *while* Iran remains under broad sanctions. Pressure will remain, but it can be calibrated so that citizens can stand up to the elite.

13. First, the West needs to create channels to allow remittances to flow into Iran, shoring up the consumption of households so that individuals can devote time and money to the protest movement. This would help make strikes more feasible, as workers could forgo wages.

14. Second, the West should create exemptions in the sanctions to allow companies and individuals abroad to hire freelancers in Iran. This would empower young, urban Iranians who are chronically underemployed, giving them breathing room to think about their political demands.

15. Third, we need to make is easier for middle class Iranians to take their money out of the country to escape the corrosive effects of inflation. This will deflate asset bubbles that emerge because sanctions act like capital controls. Those bubbles burnish the wealth of elites.

16. Taken together, these measures amount to a framework for what I call calibrated pressure. Some money flows into Iran, some flows out. But the flows, in their scale and composition, are designed to support citizens in ways that restore their power vis-a-vis elites.

17. When it comes to using economic coercion to seek behavior change or to advance political aims, preserving the economic power of the people is *as important* as seeking to constrain the economic power of the elite.

18. To secure the future that Iran’s protesters envisioned in their slogan of #WomanLifeFreedom, Iranians must first secure their livelihoods.

More details are in the essay:

foreignaffairs.com/middle-east/ho…

More details are in the essay:

foreignaffairs.com/middle-east/ho…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter