This is The Last Judgment, painted by Michelangelo nearly 500 years ago.

And it's one of the most controversial (and heavily censored) paintings of all time.

Some say it's a masterpiece, some say it's a mess, and some have even tried to destroy it...

And it's one of the most controversial (and heavily censored) paintings of all time.

Some say it's a masterpiece, some say it's a mess, and some have even tried to destroy it...

Michelangelo, born in 1475 in the Republic of Florence, quickly came to be regarded as an artistic genius. After all, he was only 24 when he sculpted the Pieta...

But he was also a painter, poet, and architect; there was nothing this tempestuous young man couldn't do.

But he was also a painter, poet, and architect; there was nothing this tempestuous young man couldn't do.

The Sistine Chapel in Rome had been constructed in the 1480s by Pope Sixtus IV, after whom it was named, and in 1508 Michelangelo was asked by Pope Julius II to paint its ceiling.

It took him four years and the result was one of the most famous works of art in the world:

It took him four years and the result was one of the most famous works of art in the world:

In 1533 Pope Clement VII asked Michelangelo to return to the Sistine Chapel and paint the wall behind its altar - he wanted a depiction of the Last Judgment as prophecised in the Bible.

Clement died but his successor, Pope Paul III, asked Michelangelo to finish this project.

Clement died but his successor, Pope Paul III, asked Michelangelo to finish this project.

Michelangelo agreed on certain conditions. For example, he had the chapel wall rebuilt with a slight incline, so that the top of the wall sticks out further than the bottom to give people at ground level a better view.

That was in 1535; the painting wasn't completed until 1541.

That was in 1535; the painting wasn't completed until 1541.

The result was far more intense, violent, and stormy than what Michelangelo had painted twenty years earlier. Why? Context, perhaps.

The Catholic Church was reeling from the Protestant Reformation, which since the 1520s had thrown Europe into religious and cultural chaos.

The Catholic Church was reeling from the Protestant Reformation, which since the 1520s had thrown Europe into religious and cultural chaos.

And, during the War of the League of Cognac, unpaid soldiers in the army of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had sacked Rome in 1527.

Michelangelo was painting Doomsday at a time when the world (at least in Rome) perhaps felt like it was coming to an end.

Michelangelo was painting Doomsday at a time when the world (at least in Rome) perhaps felt like it was coming to an end.

Michelangelo's style was often contrasted with Raphael, one of the other defining artists of the High Renaissance (alongside Leonardo).

For whereas Raphael was graceful, harmonious, and ever appropriate, Michelangelo could be turbulent, forceful, improper, and violent.

For whereas Raphael was graceful, harmonious, and ever appropriate, Michelangelo could be turbulent, forceful, improper, and violent.

The 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari, who thought Michelangelo the greatest artist of all time, called this quality "terribilita" - his power to inspire fear, awe, and sublimity.

And yet, for centuries, Raphael's gracefulness was considered the supreme goal of art.

And yet, for centuries, Raphael's gracefulness was considered the supreme goal of art.

So why was it controversial?

Here's a more traditional depiction of the Last Judgment, made by Fra Angelico in 1431. Notice its visual clarity: Jesus in the centre, surrounded by saints and angels, the damned on his left and the saved on his right. It's easy to follow.

Here's a more traditional depiction of the Last Judgment, made by Fra Angelico in 1431. Notice its visual clarity: Jesus in the centre, surrounded by saints and angels, the damned on his left and the saved on his right. It's easy to follow.

Or, from Northern Europe, a painting of the Last Judgment by Hans Memling. This, too, has absolute clarity.

Michelangelo's version, by comparison, is rather more complicated and difficult to understand, and nor does it have the same obvious structure and colour-coding.

Michelangelo's version, by comparison, is rather more complicated and difficult to understand, and nor does it have the same obvious structure and colour-coding.

And so Michelangelo diverged from tradition in several important ways, not least by departing from the Biblical account of the Last Judgment.

For example, he did not paint Jesus seated on a throne, and nor are the angels and resurrected dead arranged as described in scripture.

For example, he did not paint Jesus seated on a throne, and nor are the angels and resurrected dead arranged as described in scripture.

The inclusion of figures from Classical mythology, such as Charon the Ferryman of Greek legend, was also controversial.

This references Dante's Inferno, from the early 14th century, which intertwines plenty of classical mythology with the Christian idea of Hell.

This references Dante's Inferno, from the early 14th century, which intertwines plenty of classical mythology with the Christian idea of Hell.

And yet Michelango did not follow Dante, his favourite poet, completely.

Whereas Fra Angelico and Memling both portrayed Hell as a grotesque and fantastical realm of fire and torture, Michelangelo tones all that down and places more emphasis on the emotional state of the damned.

Whereas Fra Angelico and Memling both portrayed Hell as a grotesque and fantastical realm of fire and torture, Michelangelo tones all that down and places more emphasis on the emotional state of the damned.

The Last Judgment also captures Michelangelo's fascination with the male form.

Jesus hadn't been portrayed as beardless for centuries (which was controversial in itself) notwithstanding that his heavily muscled body makes him look like a Greek god.

This was highly unorthodox.

Jesus hadn't been portrayed as beardless for centuries (which was controversial in itself) notwithstanding that his heavily muscled body makes him look like a Greek god.

This was highly unorthodox.

Michelangelo had long been inspired by the classical sculpture of Ancient Greece and Rome (think of his David, from 1504).

But the rediscovery of this ancient statue in Rome in 1506 provoked a more contorted, violent, expressive style, as we can see in the Last Judgment.

But the rediscovery of this ancient statue in Rome in 1506 provoked a more contorted, violent, expressive style, as we can see in the Last Judgment.

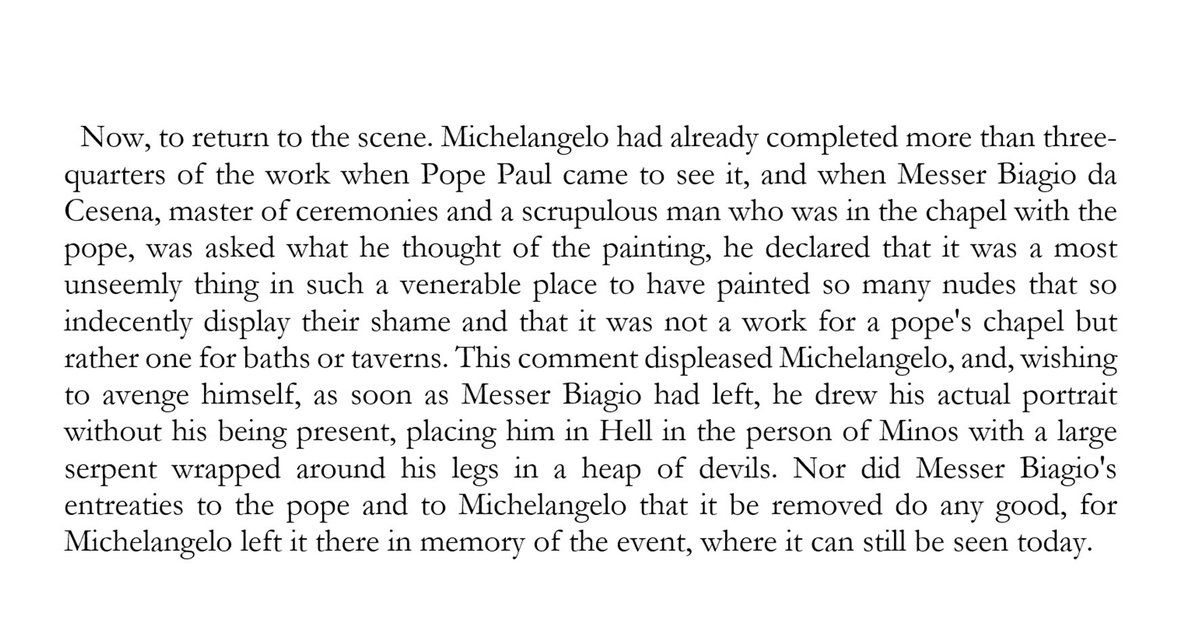

And so, even *before* it was finished, The Last Judgment was controversial.

Its departure from scripture, its complex composition, its profusion of violently contorted bodies... as Vasari writes, this was simply too much for some, especially in a place like the Sistine Chapel:

Its departure from scripture, its complex composition, its profusion of violently contorted bodies... as Vasari writes, this was simply too much for some, especially in a place like the Sistine Chapel:

Michelangelo's secret portrayal of Biagio da Cesena, who had criticised his work, remains - here we see Michelangelo's ruthless and uncompromising personality in full.

It's also another reference to Dante, where Minos was the judge of the underworld.

It's also another reference to Dante, where Minos was the judge of the underworld.

Even Michelangelo's friend, Pietro Aretino, said "I blush before the license you have used in expressing ideas connected with the highest aims and final ends to which our faith aspires."

This was the biggest controversy - the wall of the Sistine Chapel was filled with nudity.

This was the biggest controversy - the wall of the Sistine Chapel was filled with nudity.

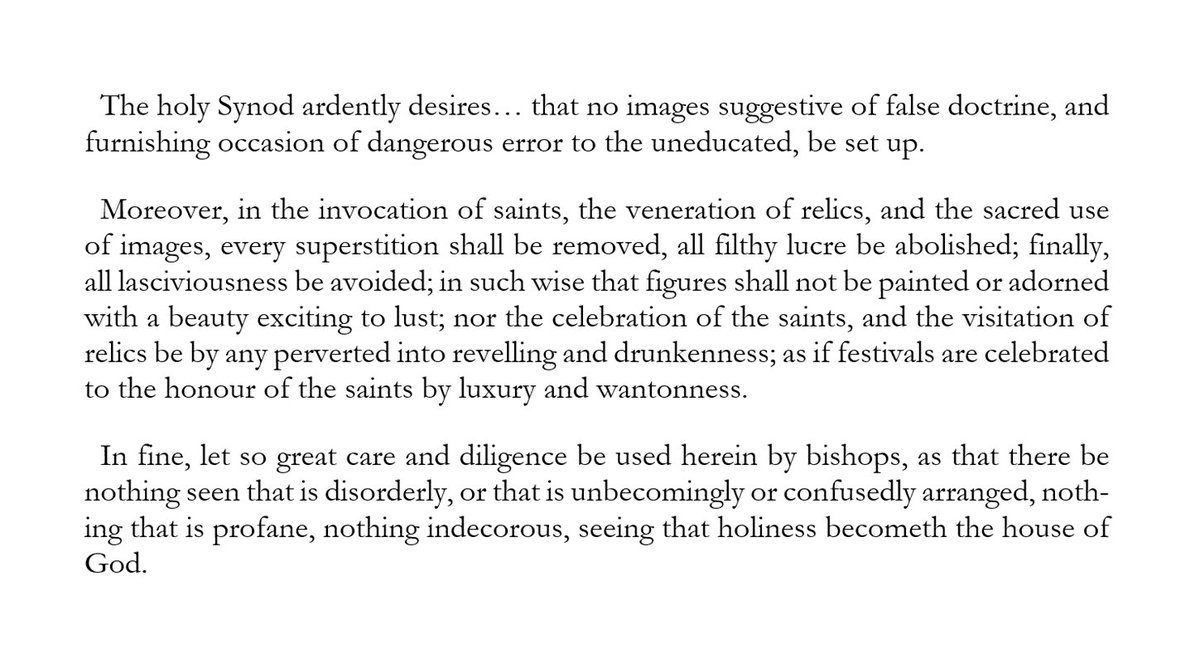

The Council of Trent was established in 1545 to guide the Catholic Church's response to the Reformation. Art was more important than ever, not least because many of the Reformers had been so critical of it.

The final session of the Council of Trent, in 1563, said this about art:

The final session of the Council of Trent, in 1563, said this about art:

Michelangelo's non-scriptural Last Judgement, a wall of three hundred confusingly arranged naked bodies, fell foul of the Council's decree.

In the year of Michelangelo's death, 1564, his former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the naked figures.

In the year of Michelangelo's death, 1564, his former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the naked figures.

Da Volterra also completely repainted Saint Catherine and Saint Blaise (recognisable by their wheel and iron combs respectively).

In Michelangelo's version Blaise had been looking at the unclothed Catherine; da Volterra dressed them and made Blaise face Jesus instead.

In Michelangelo's version Blaise had been looking at the unclothed Catherine; da Volterra dressed them and made Blaise face Jesus instead.

Despite a few more attempts to alter or remove it down the centuries, the Last Judgment has survived.

Surely one of the most unconventional and individualistic paintings there has ever been, defined entirely by Michelangelo's idiosyncratic character and personal artistic vision.

Surely one of the most unconventional and individualistic paintings there has ever been, defined entirely by Michelangelo's idiosyncratic character and personal artistic vision.

Indeed, Michelangelo even inserted himself into the painting.

Saint Bartholomew is usually depicted in Christian art with a flayed sky (in reference to how he had been killed) and Michelangelo gave this skin his own face.

Dark humour or a sign of spiritual trouble?

Saint Bartholomew is usually depicted in Christian art with a flayed sky (in reference to how he had been killed) and Michelangelo gave this skin his own face.

Dark humour or a sign of spiritual trouble?

Those controversies have faded and The Last Judgement is accepted as a masterpiece.

But... is it? Is it any better than that of Fra Angelico or Hans Memling? Is it a sublime vision or a confusing mess? Is it beautiful or inappropriate? Or perhaps, somehow, is it all of them...

But... is it? Is it any better than that of Fra Angelico or Hans Memling? Is it a sublime vision or a confusing mess? Is it beautiful or inappropriate? Or perhaps, somehow, is it all of them...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter