I remember many years ago I was invigilating an examination in Cairo University and, because the annual exams take place at the hottest time of the year, they were held in a huge marquee by the Nile.

(1/)

(1/)

Several hundred students were sitting at their desks, their whole future depending on what they wrote upon those terrible blank sheets of paper before them. A strange tension built up, almost palpable; one student after another put his or her pen down, staring into space.

(2/)

(2/)

I expected a storm to clear the air. Suddenly one student raised his head and shouted: lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāh. A sound filled the marquee, something between a sigh and a sob, and there was a ripple of laughter.

(3/)

(3/)

The students took up their pens again and went back to work. All was well.

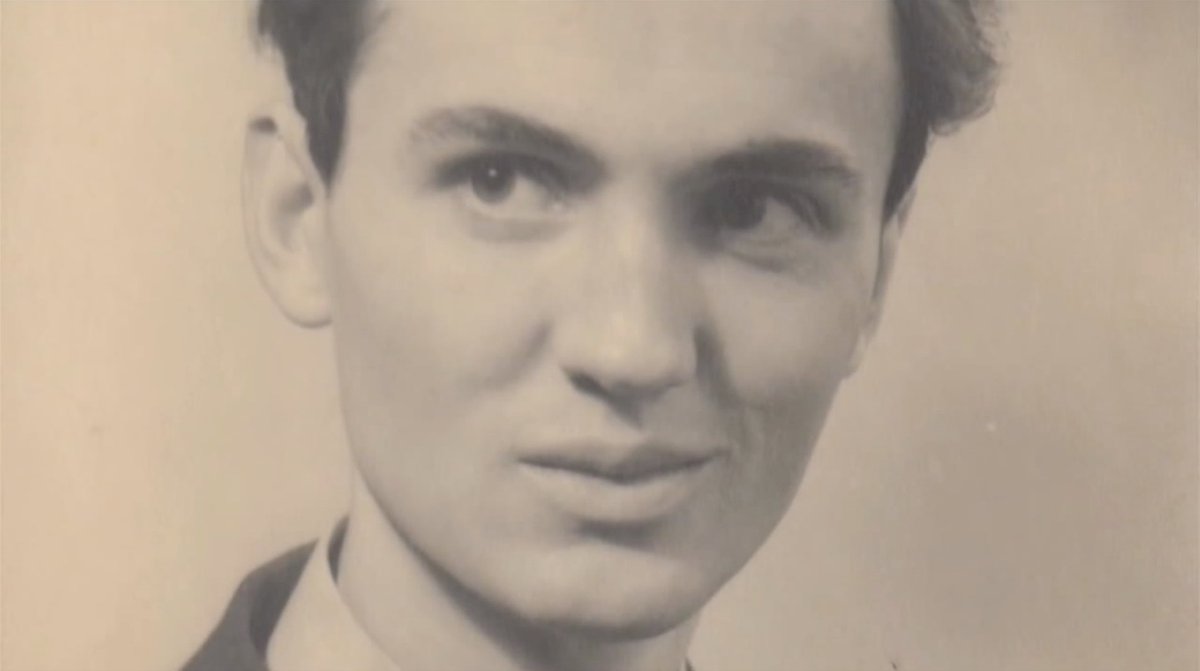

― Charles Hasan le Gai Eaton, Reflections

(4/4)

#tasawwuf

#sufism

#islamicmysticism

― Charles Hasan le Gai Eaton, Reflections

(4/4)

#tasawwuf

#sufism

#islamicmysticism

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter