This is Barcelona at night, one of the world's most unique cities. But why does it look like that?

Well, until 1855 it was overcrowded, dirty, and diseased — then something special happened.

Here is how you build a beautiful city...

Well, until 1855 it was overcrowded, dirty, and diseased — then something special happened.

Here is how you build a beautiful city...

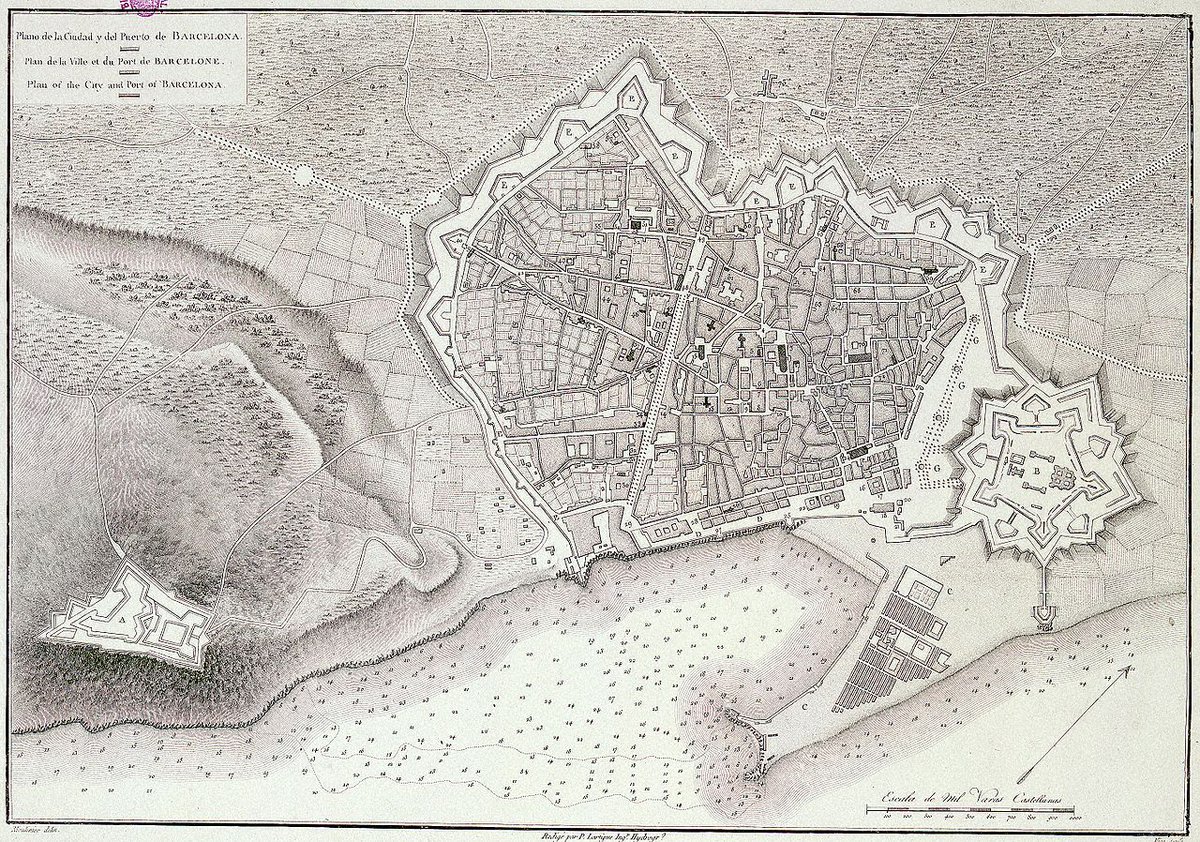

The year is 1855. Barcelona's population has nearly reached 200,000, all crammed within the two kilometres squared of the city's Medieval walls.

Overcrowding, rampant disease, crime, poor sanitation - the city had become a filthy and dangerous place.

Overcrowding, rampant disease, crime, poor sanitation - the city had become a filthy and dangerous place.

Since 1714 any construction within half a mile of the walls (the range of the cannon fire) had been forbidden.

Two hundred years later this had become a colossal hindrance; life expectancy had dropped to the mid-30s for the middle class and the mid-20s for workers.

Two hundred years later this had become a colossal hindrance; life expectancy had dropped to the mid-30s for the middle class and the mid-20s for workers.

It was also a time of unrest. For as the population of the city swelled because of industrialisation and the agricultural labourers flocking to the city for work, so too did political consciousness.

In Barcelona, in 1855, came Spain's first ever general strike.

In Barcelona, in 1855, came Spain's first ever general strike.

The situation was untenable and so the government ordered the demolition of the city's walls - after years of popular demand and political wrangling.

And a competition was announced to design the vast expansion Barcelona needed, to be known as the Eixample...

And a competition was announced to design the vast expansion Barcelona needed, to be known as the Eixample...

Enter Ildefons Cerdà, a former civil engineer who had become inspired - even obsessed - by urban planning.

He had quit his engineering job to perform social and topographical studies of Barcelona, all in preparation for a new city plan.

His time had come.

He had quit his engineering job to perform social and topographical studies of Barcelona, all in preparation for a new city plan.

His time had come.

He was a visionary. As Cerdà wrote in his monumental General Theory of Urbanisation, he realised that technology was changing the world and that a new kind of city was needed.

His chief concerns were hygiene, living standards, equality, and preparation for the modern world.

His chief concerns were hygiene, living standards, equality, and preparation for the modern world.

It was a process dogged by political machinations. Cerdà's submission won, was rejected, then accepted again in altered form.

You can see the scale of it here. The parts in black are Barcelona in 1855; everything else would be new, with six small towns annexed into Barcelona.

You can see the scale of it here. The parts in black are Barcelona in 1855; everything else would be new, with six small towns annexed into Barcelona.

One of his innovations was the chamfered corners of

Barcelona's blocks, the mansanas.

This allowed turning room and visibility for traffic, though Cerdà theorised that smaller, personal vehicles would be invented.

He anticipated the car and gave Barcelona wide avenues.

Barcelona's blocks, the mansanas.

This allowed turning room and visibility for traffic, though Cerdà theorised that smaller, personal vehicles would be invented.

He anticipated the car and gave Barcelona wide avenues.

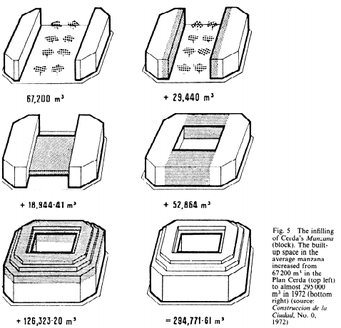

Cerdà's proposed blocks were built around large gardens; this was about hygiene, sunlight, and quality of life for every citizen, however rich or poor.

But Cerdà's utopia was not realised - the blocks were built up and the gardens filled in.

But Cerdà's utopia was not realised - the blocks were built up and the gardens filled in.

Still, the unprecedented construction of the Eixample continued.

A key moment came when Barcelona was chosen to host the Universal Exposition in 1888. The world's attention would be turned on Barcelona - here was a chance to create a truly distinctive and modern city.

A key moment came when Barcelona was chosen to host the Universal Exposition in 1888. The world's attention would be turned on Barcelona - here was a chance to create a truly distinctive and modern city.

The citadel, just outside the old walls, was demolished and replaced with the Parc de la Ciutadella.

Preparation for the Universal Exposition also saw the construction of many other buildings and features of the city which survive to this day.

Preparation for the Universal Exposition also saw the construction of many other buildings and features of the city which survive to this day.

Like the Arc de Triomf, designed by Josep Vilaseca i Casanovas, immediately recognisable by its red bricks.

What had started with the Eixample, an urban renewal and expansion project, was morphing into something more...

What had started with the Eixample, an urban renewal and expansion project, was morphing into something more...

Because, suddenly, Barcelona and Catalonia had an architectural style all of their own: Catalan Modernism.

It was, broadly speaking, a sub-genre of Art Nouveau, inspired by the same design principles and creative philosophies that swept Europe in the 1880s and 1890s.

It was, broadly speaking, a sub-genre of Art Nouveau, inspired by the same design principles and creative philosophies that swept Europe in the 1880s and 1890s.

But this continental movement took on a unique form in Catalonia, spurred on by a greater sense of cultural identity.

A crop of immensely talented, experimental architects appeared: Antoni Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, and Josep Puig i Cadafalch foremost among them.

A crop of immensely talented, experimental architects appeared: Antoni Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, and Josep Puig i Cadafalch foremost among them.

Gaudí's work - the Sagrada Família, the Parc Güell, the Casa Batlló, the Pedrera - may be the most famous.

But they only represent a small portion of the wildly idiosyncratic, eternally delightful architecture that filled Barcelona in the decades after the Universal Exhibition.

But they only represent a small portion of the wildly idiosyncratic, eternally delightful architecture that filled Barcelona in the decades after the Universal Exhibition.

Just consider the Palau de la Música Catalana, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner and completed in 1908.

Barcelona had come a long way since the cramped Medieval city of five decades earlier; the Renaixença - the Catalan Renaissance - had come to fruition.

Barcelona had come a long way since the cramped Medieval city of five decades earlier; the Renaixença - the Catalan Renaissance - had come to fruition.

And so, eventually, Cerdà's (somewhat altered) Eixample was completed.

Barcelona has seen more expansion since, but most of it has been inspired by, if not the specific principles of the Eixample, then the architectural, civic, artistic, and urban values it inculcated.

Barcelona has seen more expansion since, but most of it has been inspired by, if not the specific principles of the Eixample, then the architectural, civic, artistic, and urban values it inculcated.

And so Cerdà's visionary plan, combined with the flowering of Catalan Modernism, has been an unprecedented success.

He had prepared his city for the future and given it, even incidentally and through the many who followed in his footsteps, an entirely unique identity.

He had prepared his city for the future and given it, even incidentally and through the many who followed in his footsteps, an entirely unique identity.

Cerdà wasn't the first urban planner.

London had been rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666, Paris was transformed by Haussmann, and in the ancient world there was a long tradition of grid-based city layouts.

Like the Roman city of Timgad in Algeria.

London had been rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666, Paris was transformed by Haussmann, and in the ancient world there was a long tradition of grid-based city layouts.

Like the Roman city of Timgad in Algeria.

What makes Cerdà special is that he dealt so directly (and innovatively) with the wave of modernisation reshaping the world, and performed an unprecedented level of research into public health and urban form.

Cerdà is, perhaps, the founder of modern urbanism.

Cerdà is, perhaps, the founder of modern urbanism.

And nor did Barcelona, as so many places have done, demolish its Medieval city.

The walls went, but the tightly packed Gothic quarter, with its narrow streets, paved squares, and churches remains intact (albeit with some 19th century meddling).

A city Medieval and Modern.

The walls went, but the tightly packed Gothic quarter, with its narrow streets, paved squares, and churches remains intact (albeit with some 19th century meddling).

A city Medieval and Modern.

Ildefons Cerdà died in 1876; he never lived to see the jewel that Barcelona would become, one of the world's most beloved cities. But his dream, however wild it once was, has come true.

Here is his gravestone. An appropriate monument to one of history's greatest urban planners.

Here is his gravestone. An appropriate monument to one of history's greatest urban planners.

If you found this interesting then you may like my newsletter, where I've written about Catalan Modernism before.

Seven short lessons. Every Friday. All free.

To join 75k+ other readers, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

Seven short lessons. Every Friday. All free.

To join 75k+ other readers, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh