The most interesting Roman isn't a philosopher like Marcus Aurelius or a conqueror like Julius Caesar.

It's Pliny the Younger, who was... a normal person.

Here are some highlights from the wit & wisdom of his letters. They're 2,000 years old, but they haven't aged a day:

It's Pliny the Younger, who was... a normal person.

Here are some highlights from the wit & wisdom of his letters. They're 2,000 years old, but they haven't aged a day:

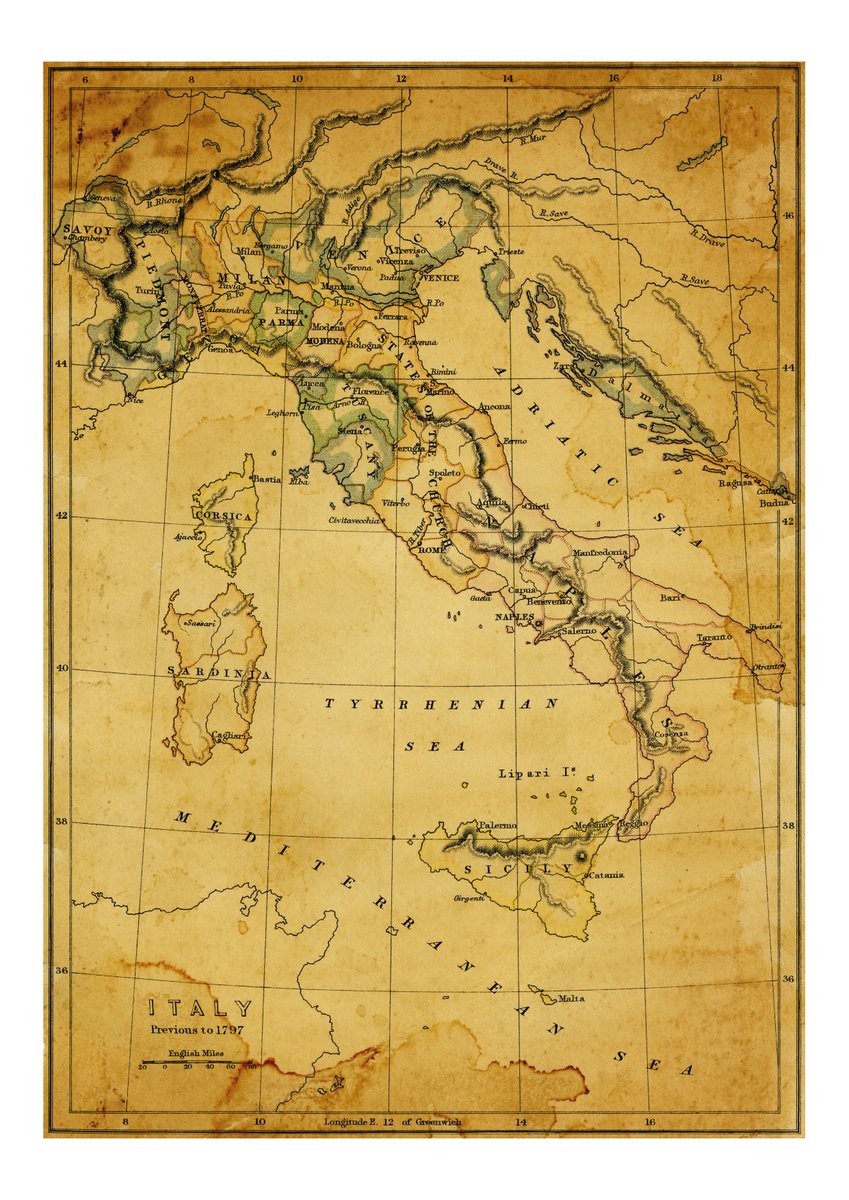

Gaius Caecilius was born in 61 AD near Lake Como in northern Italy. He was raised by his mother and travelled to Rome as a young man.

There he was educated by his uncle, the famous polymath Gaius Plinius Secundus, known in English as Pliny the Elder.

There he was educated by his uncle, the famous polymath Gaius Plinius Secundus, known in English as Pliny the Elder.

He adopted Gaius Caecilius as a son and, before his death during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, made him his heir.

Thereafter the young man added Plinius Secundus to his own name and became... Pliny the Younger.

Thereafter the young man added Plinius Secundus to his own name and became... Pliny the Younger.

Pliny studied under the great rhetorician Quintilian and at 18 embarked on a long and successful legal career.

Though his specialism was inheritance, Pliny took part in many high-profile cases, including the prosecution and defence of provincial governors accused of corruption.

Though his specialism was inheritance, Pliny took part in many high-profile cases, including the prosecution and defence of provincial governors accused of corruption.

He held every role in the cursus honorum — the Roman system of political and administrative offices — from military tribune through to consul, and worked in the Treasury, too.

His final position was as governor of the province of Bithynia, in modern Turkey, under Trajan.

His final position was as governor of the province of Bithynia, in modern Turkey, under Trajan.

There he proved himself a considerate and devoted administrator, committed to reforming the financial irregularities and logistical failings of the area.

It was while serving as the governor of Bithynia that he died in 113 AD, aged fifty two.

What makes Pliny special, then?

It was while serving as the governor of Bithynia that he died in 113 AD, aged fifty two.

What makes Pliny special, then?

The rule of Domitian, 81-96 AD, had been a time of exiles, executions, and oppression. But Pliny survived Domitian's reign of terror unscathed.

This might cast doubt on his integrity. How could a principled man work under an emperor condemned, even in his own time, as evil?

This might cast doubt on his integrity. How could a principled man work under an emperor condemned, even in his own time, as evil?

Pliny, like Tacitus, his close friend and the greatest of all Roman historians, sought to carve out a middle-ground between full resistance (like the Stoics who had opposed Nero & Domitian) and total obsequience.

Pliny was, in many ways, the ideal civil servant.

Pliny was, in many ways, the ideal civil servant.

In good times or bad he endured, doing whatever was within his often limited grasp to bolster justice, right wrongs, soften evils, support the needy, and keep the gears of the nation operating.

Although a friend of the Stoics, Pliny was by his own admission not a philosopher.

Although a friend of the Stoics, Pliny was by his own admission not a philosopher.

Practical matters were his chief concern — how to get on with managing a large and complex society where food, safety, education, and tax rather than philosophy were what mattered to most people.

The Stoic resistance may be famous, but what good did it do for the average Roman?

The Stoic resistance may be famous, but what good did it do for the average Roman?

But Pliny the Younger is remarkable not so much for his political and legal career as his letters, which were widely published in his own lifetime.

The epic poetry, great deeds, and art of Rome can feel distant — but the ancient world comes to life with Pliny.

The epic poetry, great deeds, and art of Rome can feel distant — but the ancient world comes to life with Pliny.

His many letters, surprisingly relatable and deeply revealing, convey to us a uniquely personal view of Roman lives and Roman ways.

As when Pliny writes, without any hint of irony or shame, about how much he loves his friends:

As when Pliny writes, without any hint of irony or shame, about how much he loves his friends:

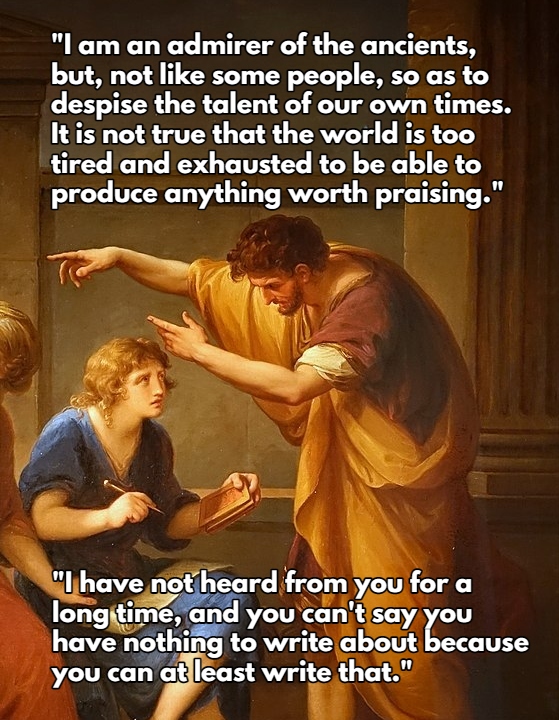

Striking above all is his staunch optimism.

Whereas it was normal in the Roman Empire to lament the state of modern culture, comparing it unfavourably with the great glories of the Republic, Pliny was forthright in his belief that the present could be just as good as the past:

Whereas it was normal in the Roman Empire to lament the state of modern culture, comparing it unfavourably with the great glories of the Republic, Pliny was forthright in his belief that the present could be just as good as the past:

Pliny also wrote about very much the same things we do... such as chiding friends for not replying to his letters often enough. Or, in modern terms, being left on read.

He often wrote to his wife, telling her how much he missed her.

And here we see something fairly uncommon in Greek and Roman history — real, domestic love, rather than lyric poetry and mythology.

And here we see something fairly uncommon in Greek and Roman history — real, domestic love, rather than lyric poetry and mythology.

And many of Pliny's letters are strikingly modern. Or, at least, the feelings he expresses seem no less applicable now than they did when he wrote them nearly 2,000 years ago.

Many people will understand his confusion at the popularity of sport and the zeal of fans:

Many people will understand his confusion at the popularity of sport and the zeal of fans:

Here is not a general, a conqueror, a philosopher, or a poet. What we get with Pliny's letters is a real, fully-formed person, one we can clearly imagine and even understand.

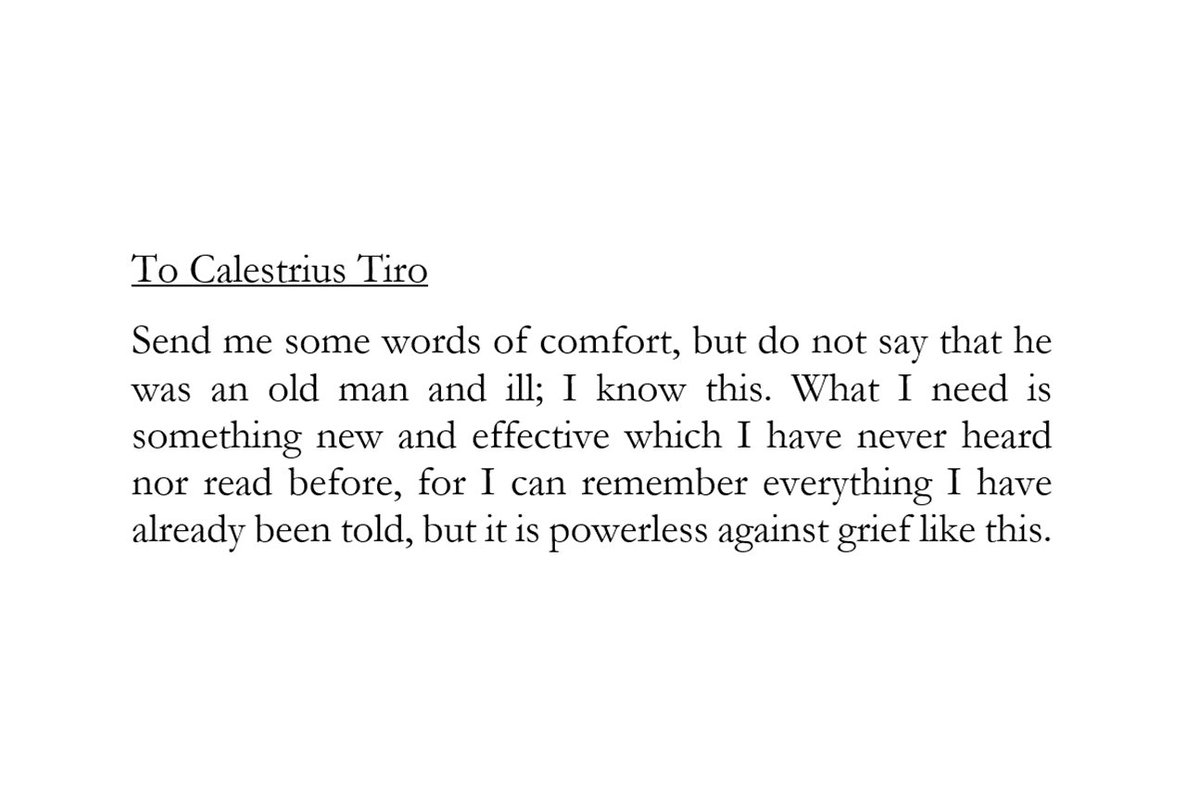

Whether praising his friends or asking them for help when dealing with grief.

Whether praising his friends or asking them for help when dealing with grief.

We learn what he loves, like literature — including who his favourite writers were and what the literary scene in Rome was like — and what upsets him, such as his wife's ill-health.

Pliny's letters also reveal much about life in Rome in the 1st century AD, from descriptions of the landscape to the politics and business of the city to the inner-workings of the courts and legal system.

Even the housing market:

Even the housing market:

And though he was not a philosopher, usually preferring to discuss poetry, gossip, or ongoing legal cases, Pliny does offer some thoughts about life in general.

Characterised, as ever, by moderation and reason and a great deal of sympathy.

Characterised, as ever, by moderation and reason and a great deal of sympathy.

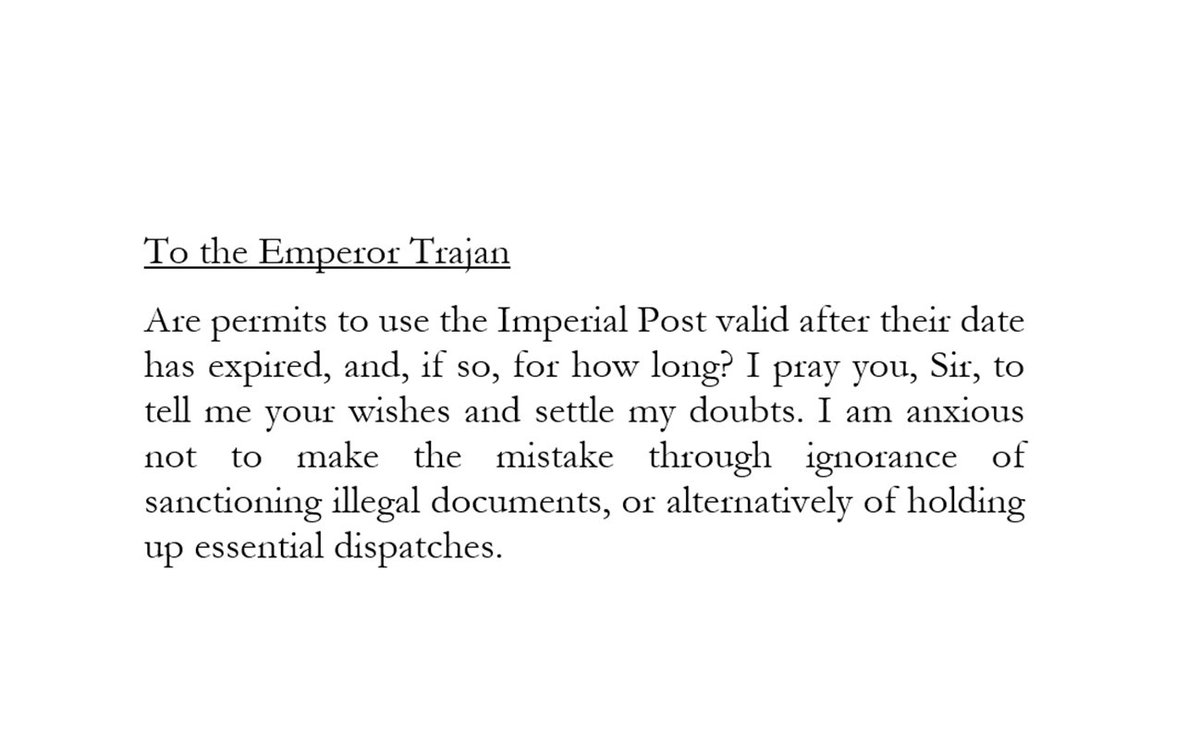

Pliny often wrote to Trajan while he was the governor of Bithynia, consulting the emperor on matters great and small.

Including... his confusion about how to use the imperial postal service.

Including... his confusion about how to use the imperial postal service.

And this excerpt rather sums up the man he was: not a great poet or philosopher, neither a ruler nor warrior, but a passionate friend and a practical man of profound humility, energy, and hope.

Ancient Rome can be rather impersonal: majestic statues, grand mythology, lofty philosophers, and great conquerors.

Pliny the Younger bridges that gulf and speaks to us directly as a human being — one who seems to remind us how little people have changed.

Pliny the Younger bridges that gulf and speaks to us directly as a human being — one who seems to remind us how little people have changed.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter