Why read a self-help book published in 2023 when you could read one that was a best seller for 1,500 years?

This is the Consolation of Philosophy, written by a man called Boethius while he was in prison, awaiting execution, in 523 AD.

Here are its 8 most powerful ideas:

This is the Consolation of Philosophy, written by a man called Boethius while he was in prison, awaiting execution, in 523 AD.

Here are its 8 most powerful ideas:

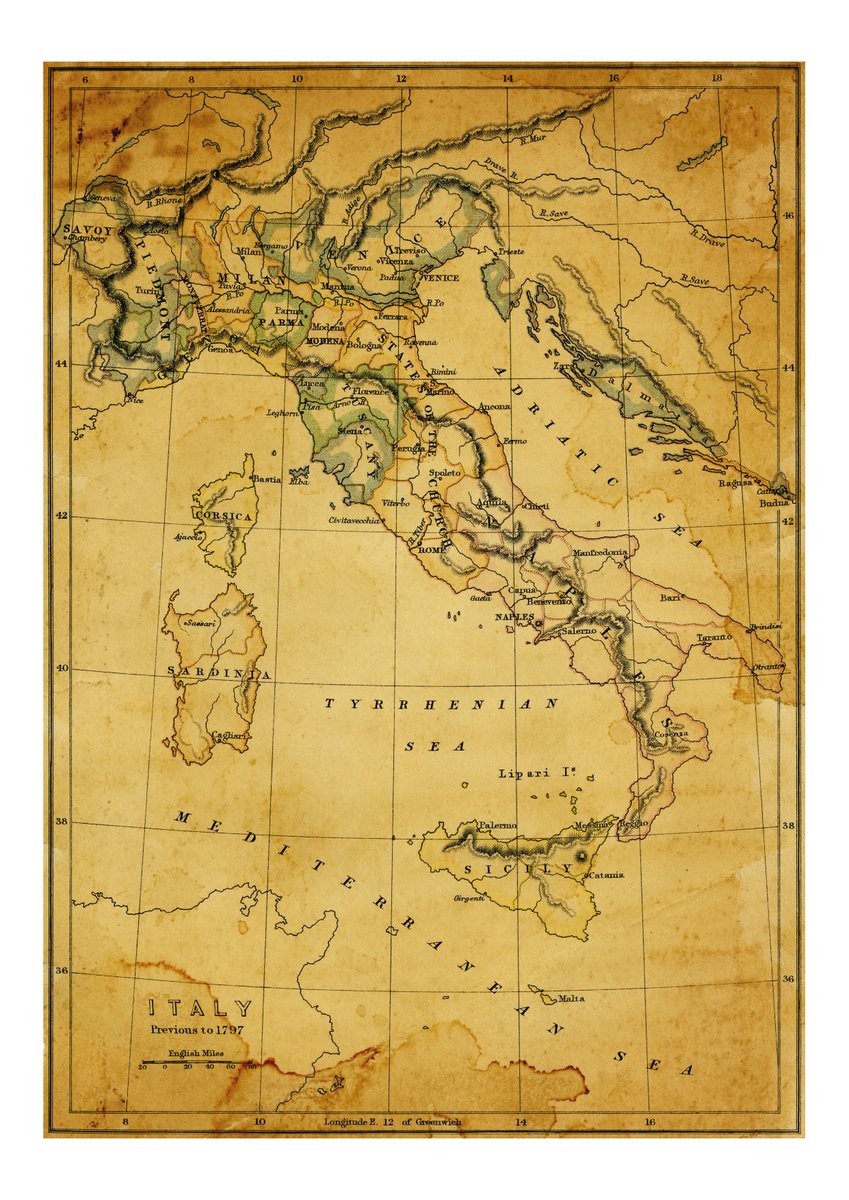

Boethius was born in 480 AD to a rich, powerful, and aristocratic family in Rome.

Though his father died when he was young, Boethius was adopted by an influential politician called Symmachus.

Boethius had a lucky start in life — and he made the most of it.

Though his father died when he was young, Boethius was adopted by an influential politician called Symmachus.

Boethius had a lucky start in life — and he made the most of it.

Before the age of 30 he had become consul — the most prestigious role in Roman society, usually reserved for older men.

Ten years later his two sons were made joint consuls as a tribute to Boethius, who had become the most important politician and writer in Italy.

Ten years later his two sons were made joint consuls as a tribute to Boethius, who had become the most important politician and writer in Italy.

Soon enough King Theoderic promoted Boethius to the role of Magister Officiorum, and he went to join the king's court in Ravenna, where he helped rule the whole kingdom.

Boethius had family, friends, and influence; he was rich, powerful, and respected. Life was good.

Boethius had family, friends, and influence; he was rich, powerful, and respected. Life was good.

But everything fell apart.

A senator called Albinus was falsely accused of plotting against the king. Boethius defended Albinus but Theoderic was paranoid about a potential revolt against his rule.

Albinus was executed and Boethius was thrown into prison...

A senator called Albinus was falsely accused of plotting against the king. Boethius defended Albinus but Theoderic was paranoid about a potential revolt against his rule.

Albinus was executed and Boethius was thrown into prison...

Theoderic ordered the Senate to decide Boethius' fate. A special court was convened and they found him guilty of treason; he was sentenced to death.

And it was here, awaiting execution in the year 523, that Boethius wrote a short book called the Consolation of Philosophy.

And it was here, awaiting execution in the year 523, that Boethius wrote a short book called the Consolation of Philosophy.

It takes the form of a dialogue between Boethius, wallowing in jail, and Philosophy, allegorised as an ethereal woman.

The Consolation, which mixes prose and poetry, begins with Boethius lamenting his situation and his "unfair" imprisonment.

Philosophy's teaching begins...

The Consolation, which mixes prose and poetry, begins with Boethius lamenting his situation and his "unfair" imprisonment.

Philosophy's teaching begins...

1. Fortune

Philosophy explains to Boethius that Fortune is an inevitable part of human life, and that history shows how unpredictable events are, how suddenly things change, and how we can never foresee what will happen to us.

It is, simply, the way of life.

Philosophy explains to Boethius that Fortune is an inevitable part of human life, and that history shows how unpredictable events are, how suddenly things change, and how we can never foresee what will happen to us.

It is, simply, the way of life.

But Philosophy also points out that Boethius can't complain how "unfairly" he has been treated if he was happy to enjoy the good things Fortune gave him — besides, the good has far outweighed the bad in his life.

And bad times, just like the good, must also pass in the end.

And bad times, just like the good, must also pass in the end.

This is the metaphorical Wheel of Fortune, which lifts us up and casts us down seemingly at random, bringing us good times and then bad no matter what we want or try to do.

This was an idea popularised by Boethius — and still familiar to us today.

This was an idea popularised by Boethius — and still familiar to us today.

2. Bad Fortune is Useful

Philosophy then explains how it is good for us to experience a reversal of fortune in our lives.

This allows us to understand the nature of fortune and the world more clearly. It prepares us for future bad times and ensures we enjoy the good times more.

Philosophy then explains how it is good for us to experience a reversal of fortune in our lives.

This allows us to understand the nature of fortune and the world more clearly. It prepares us for future bad times and ensures we enjoy the good times more.

And so, Philosophy concludes:

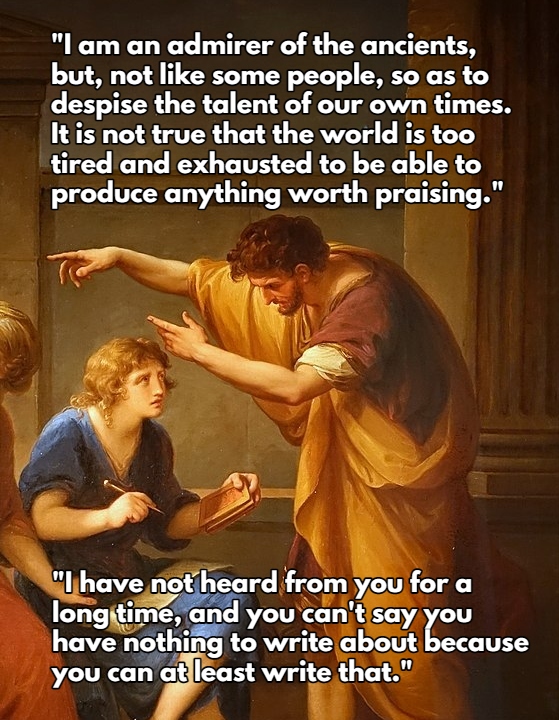

"All fortune is good fortune; for it either rewards, disciplines, amends, or punishes, and so is either useful or just."

A profound realisation for a man unfairly facing the death penalty: there is good in everything that happens.

"All fortune is good fortune; for it either rewards, disciplines, amends, or punishes, and so is either useful or just."

A profound realisation for a man unfairly facing the death penalty: there is good in everything that happens.

3. We Have More Than We Realise

Philosophy points out that Boethius, even in prison, still has more than many people could ever dream of.

His two sons are alive, healthy, and successful; his adoptive father, Symmachus, too; he still has food, water, shelter, and books.

Philosophy points out that Boethius, even in prison, still has more than many people could ever dream of.

His two sons are alive, healthy, and successful; his adoptive father, Symmachus, too; he still has food, water, shelter, and books.

Philosophy asks him an important question:

"How many people exist, do you reckon, who would think that they were in heaven if they enjoyed the merest fraction of the fortune which is still yours?"

However much we think we are suffering, there are others far less fortunate.

"How many people exist, do you reckon, who would think that they were in heaven if they enjoyed the merest fraction of the fortune which is still yours?"

However much we think we are suffering, there are others far less fortunate.

4. Who Is Happy, Anyway?

But Philosophy argues that nobody is ever truly happy, nor has everything they want.

Everybody is always lacking one thing and worried about another. Even those who seem happy are always bothered by something and therefore not fully satisfied with life.

But Philosophy argues that nobody is ever truly happy, nor has everything they want.

Everybody is always lacking one thing and worried about another. Even those who seem happy are always bothered by something and therefore not fully satisfied with life.

5. External Things Do Not Make Us Happy

Which leads Philosophy to conclude that placing value on external, material things will never satisfy us.

She asks Boethius if, even when he was rich and powerful, he was ever completely happy and free of worries.

Which leads Philosophy to conclude that placing value on external, material things will never satisfy us.

She asks Boethius if, even when he was rich and powerful, he was ever completely happy and free of worries.

Philosophy dismantles material pursuits one by one, including power, wealth, fame, and physical pleasures and vices.

Here, discussing fame, Philosophy explores how small and how brief it is; this so-called "fame" is really just an illusion which will inevitably fade away.

Here, discussing fame, Philosophy explores how small and how brief it is; this so-called "fame" is really just an illusion which will inevitably fade away.

Those with power or wealth always fear losing them and never have peace of mind; those who pursue fame are pursuing an illusion; physical pleasures always leave us unfulfilled and wanting more.

Nothing external can make us truly satisfied or truly happy.

Nothing external can make us truly satisfied or truly happy.

6. The Source of Real Happiness

Since external routes to happiness — wealth, power, fame, pleasures — by their very nature can never make us truly happy, the real source of happiness must be internal.

For what is internal can never be affected by the wheel of fortune.

Since external routes to happiness — wealth, power, fame, pleasures — by their very nature can never make us truly happy, the real source of happiness must be internal.

For what is internal can never be affected by the wheel of fortune.

Philosophy calls this virtue; happiness is irrevocably intertwined with the idea of good.

If we are good then we are happy; if we are happy then we must also be good.

"One's virtue is all that one truly has, because it is not imperiled by the vicissitudes of fortune."

If we are good then we are happy; if we are happy then we must also be good.

"One's virtue is all that one truly has, because it is not imperiled by the vicissitudes of fortune."

This produces a profound realisation: that only those who are internally happy have any real power, wealth, or pleasure.

All humans seek happiness, but those who do so through external means are never satisfied, and that which cannot satisfy itself surely has no power.

All humans seek happiness, but those who do so through external means are never satisfied, and that which cannot satisfy itself surely has no power.

7. Bad People Suffer Most

Since people who do bad things are not good, they are logically not happy either.

So if people do bad things — even to us — it is they who suffer most, because what they have done is a result of deep unhappiness.

Since people who do bad things are not good, they are logically not happy either.

So if people do bad things — even to us — it is they who suffer most, because what they have done is a result of deep unhappiness.

8. Nothing Bad Can Happen to a Good Person

All of which builds to one of the Consolation's most powerful ideas: that if we are truly happy then no external factors, no matter how bad they are, can ever change that.

A person at peace with themselves is all-powerful.

All of which builds to one of the Consolation's most powerful ideas: that if we are truly happy then no external factors, no matter how bad they are, can ever change that.

A person at peace with themselves is all-powerful.

Or, as Philosophy says:

"Nothing is miserable unless you think it so; and on the other hand, nothing brings happiness unless you are content with it."

And so, facing death, Boethius was not miserable. Philosophy consoled him, and he found happiness at the very end of his life.

"Nothing is miserable unless you think it so; and on the other hand, nothing brings happiness unless you are content with it."

And so, facing death, Boethius was not miserable. Philosophy consoled him, and he found happiness at the very end of his life.

After his death the Consolation (which has been simplified here) was translated and printed by every generation throughout the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and into the 20th century.

If there had been charts, it would have been a best-seller for 1,500 years...

If there had been charts, it would have been a best-seller for 1,500 years...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter