As parliament debate #AccessToNature today, a personal essay.

Deep in my valley is a tree so old it makes my bones ache. There are only a handful like it in the country, and its boughs harbour some of our oldest stories.

Yet almost no-one has ever seen it. 🧵

Deep in my valley is a tree so old it makes my bones ache. There are only a handful like it in the country, and its boughs harbour some of our oldest stories.

Yet almost no-one has ever seen it. 🧵

That’s because it resides on a 5,000 acre private estate at the border of England & Wales.

The estate is old: Norman Conquest old. With the same family, the Scudamores, holding it since the 11th century.

But the tree is older still...

The estate is old: Norman Conquest old. With the same family, the Scudamores, holding it since the 11th century.

But the tree is older still...

The Jack O’Kent Oak is named after a folk trickster of the border country, famed for outwitting the devil. Jack is said to have tied his hounds to the tree’s trunk, and discoursed with the devil from its branches.

He is our valley’s Twm Siôn Cati. Our poundshop Doctor Faustus.

He is our valley’s Twm Siôn Cati. Our poundshop Doctor Faustus.

So, the tree is famous. But famous for who?

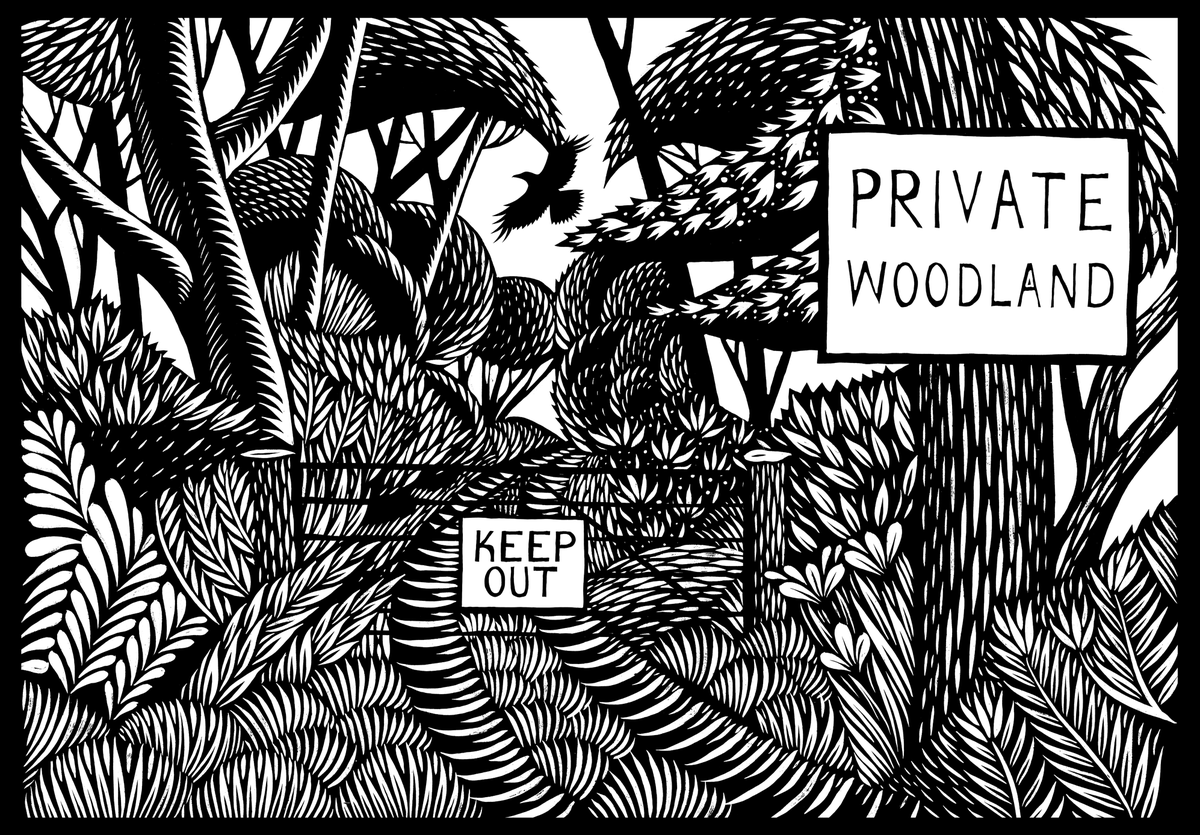

As the website reads, “The deer park is permanently closed to the public.”

Or so it is today. The historical record reveals a different story.

As the website reads, “The deer park is permanently closed to the public.”

Or so it is today. The historical record reveals a different story.

Old maps show a public footpath crosses the estate, connecting the village below to the common above.

Yet at some point in the mid 20th century, it “disappeared” from the Ordnance Survey.

It passes right by the tree.

Yet at some point in the mid 20th century, it “disappeared” from the Ordnance Survey.

It passes right by the tree.

I don’t know how the path got magicked off the map.

But Kentchurch is not alone in being a large estate with a spectral footpath. Many used their power to redesign the Definitive Map in their interests. And if the cut-off deadline is not removed, they could be lost forever.

But Kentchurch is not alone in being a large estate with a spectral footpath. Many used their power to redesign the Definitive Map in their interests. And if the cut-off deadline is not removed, they could be lost forever.

Worse than lost footpaths, across the country, whole villages were moved or destroyed to make space for estate parklands; all to create a picturesque of confected isolation.

So I set off to document the old path. ‘Trespassing’ the line where old rights still glimmer if you know where to look; connecting a heritage once held by everyone – and now by no one at all.

Initially, the weather was... unfavourable.

Initially, the weather was... unfavourable.

…But it soon cleared up. And, as I dropped off the common at Garway Hill, I started to notice hints of what had once been.

Like this stile: now obscured by barbed wire.

Like this stile: now obscured by barbed wire.

The further I went the more traces I found. Sunken tracks worked into the hillside by generations of feet, carts, wildlife, livestock.

Sites of movement, but also connection: linking commons, communities and their stories together.

Sites of movement, but also connection: linking commons, communities and their stories together.

Now, there was no one.

I scrambled over the deer fence and took in the view. Ravens cronked above, a Great Tit kicked off in the nearby scrub. Otherwise, silence.

Later, I’d stumble across an old cottage in the adjacent wood, long abandoned too.

I scrambled over the deer fence and took in the view. Ravens cronked above, a Great Tit kicked off in the nearby scrub. Otherwise, silence.

Later, I’d stumble across an old cottage in the adjacent wood, long abandoned too.

Heading deeper into the park, I searched for the great oak.

It’s claimed Britain has so many ancient trees due to the preservation of estates like this. On the continent, revolution came, & erstwhile estate woodlands were converted into forestry, their veteran trees hacked down.

It’s claimed Britain has so many ancient trees due to the preservation of estates like this. On the continent, revolution came, & erstwhile estate woodlands were converted into forestry, their veteran trees hacked down.

Silver linings, perhaps? Except, of course, many estates in Britain did the same thing.

And as I walked through the park, it seemed the superabundance of fallow deer was steadily killing off much of the medieval wood pasture, converting it to heathland.

And as I walked through the park, it seemed the superabundance of fallow deer was steadily killing off much of the medieval wood pasture, converting it to heathland.

Despite that, it must be said that large parts of this estate were in much better condition than the land around them.

No industrial farming here, and some gorgeous messy habitat outside of the deer fence, where nature is abundant. Here's a vid from a trip with my friend Rosie.

No industrial farming here, and some gorgeous messy habitat outside of the deer fence, where nature is abundant. Here's a vid from a trip with my friend Rosie.

I traced the footpath - now a track for the keeper’s 4x4 - to the centre of the park. And there I found it: the Jack O’Kent Oak in all its gnarly splendour.

Bees had built a nest in one of its hollows. I could see the charred memento of a lightning strike in its tops.

Bees had built a nest in one of its hollows. I could see the charred memento of a lightning strike in its tops.

And at its foot: a seat.

And so I sat. Perhaps for half an hour, maybe more.

I find being with something so old yet alive does unusual things to the mind. Time stretches. There’s a reorientation of the ego, a dual sense of finitude amid infinity that's strangely comforting.

And so I sat. Perhaps for half an hour, maybe more.

I find being with something so old yet alive does unusual things to the mind. Time stretches. There’s a reorientation of the ego, a dual sense of finitude amid infinity that's strangely comforting.

...though perhaps a little less when I’m worried about being busted by the keeper. A 4x4 sailed by in the distance. Happily, they didn't see me.

Trees like this oak root religions, seed stories. They are sacred in a way that is both soft & open.

But when we enclose culture behind fences we amputate those stories from their source. The less we have these old things to anchor us, the harder it is for something new to grow.

But when we enclose culture behind fences we amputate those stories from their source. The less we have these old things to anchor us, the harder it is for something new to grow.

When campaigning for @Right_2Roam I’m often asked: “you already have 140,000 miles of footpath! Why do you need more?”

And there are many practical answers: the fate of Kentchurch’s footpath illustrates one.

And there are many practical answers: the fate of Kentchurch’s footpath illustrates one.

But there’s something deeper in that question that I find saddening.

Because when someone asks "Why do you need more?” I want to respond with the simple, obvious question:

Why do you need less?

Because when someone asks "Why do you need more?” I want to respond with the simple, obvious question:

Why do you need less?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh