“Funny” story: the US used to have a whole industry of private investigative epidemiologists people could hire to trace the source of their illness.

Why? Because there used to be a lot more really awful infectious diseases and people are willing to pay when the stakes are high.

Why? Because there used to be a lot more really awful infectious diseases and people are willing to pay when the stakes are high.

https://twitter.com/sinz54/status/1659144923793469441

Morale of this story: when rich people don’t have good options to protect themselves and their families, capitalism finds a way.

We have good tools we could use. But if we don’t use them, people are very likely going to get litigative.

We have good tools we could use. But if we don’t use them, people are very likely going to get litigative.

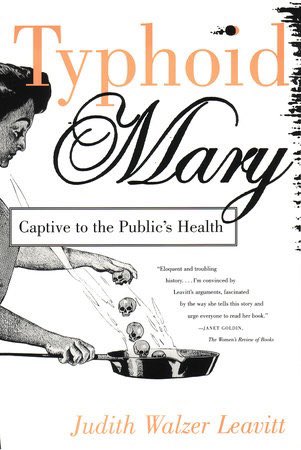

Curious to read more? I recommend Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health. By Judith Walzer Leavitt

Back in 2020, we read this book together as part of the #EpiBookClub. Check out the tweets below👇🏼 and at #TyphoidMaryBook

https://twitter.com/epiellie/status/1269384697299296256

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter