This is the Queen's Stepwell in Gujarat, India, built nearly 1,000 years ago.

It is beautiful, but it isn't unique — India is filled with hundreds of stepwells just like it.

Here is the story of the world's most extraordinary underground architecture...

It is beautiful, but it isn't unique — India is filled with hundreds of stepwells just like it.

Here is the story of the world's most extraordinary underground architecture...

Water management was (and remains) one of the biggest challenges for any human civilisation.

When you have a large group of people living in one place you need to provide water for drinking, bathing, washing, and the irrigation of crops.

The only question is: how?

When you have a large group of people living in one place you need to provide water for drinking, bathing, washing, and the irrigation of crops.

The only question is: how?

In India, sometime between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD, there arose a very special way of managing water: stepwells, known variously as baoli, bawri, or vav.

They were a solution to the problem of water supply in arid regions without consistent rainfall.

They were a solution to the problem of water supply in arid regions without consistent rainfall.

Why are they called stepwells? It's in the name.

Like all wells, they are essentially just holes down to the water table, which is where the earth is saturated with water.

The difference is that they incorporate steps or terraces leading down to the bottom.

Like all wells, they are essentially just holes down to the water table, which is where the earth is saturated with water.

The difference is that they incorporate steps or terraces leading down to the bottom.

The first stepwells were relatively simple — perhaps something like this, the Adi Kadi Vav, carved straight into the rock.

But they rapidly became larger, more complex, and more ambitious. Many go five storeys deep into the earth; some go even further than that.

But they rapidly became larger, more complex, and more ambitious. Many go five storeys deep into the earth; some go even further than that.

Stepwells have several ingenious design features.

In order to deal with the inconsistent weather of regions which were dry for most of the year and then soaked in the rainy season, they act as cisterns which fill to the brim during heavy rainfall — water storage.

In order to deal with the inconsistent weather of regions which were dry for most of the year and then soaked in the rainy season, they act as cisterns which fill to the brim during heavy rainfall — water storage.

And, by virtue of their steps, they allow the water to be accessed at any time, no matter how high or low its level is.

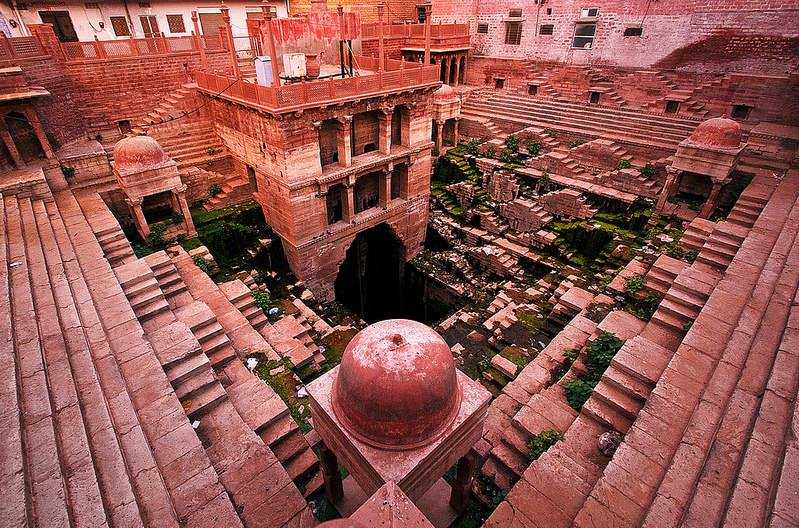

This is Toorji's Stepwell, built in the 1740s, seen at two different points in the year.

This is Toorji's Stepwell, built in the 1740s, seen at two different points in the year.

But what started as a way of effectively accessing water became something more, and one of the world's most extraordinary architectural traditions was born.

These stepwells were a crucial part of everyday life; their architecture soon reflected this importance.

These stepwells were a crucial part of everyday life; their architecture soon reflected this importance.

And the design of stepwells evolved to meet the challenges of their changing use.

Some of them incorporated covered galleries to provide relief from the heat of sun, along with space to shelter for travellers, traders, and pilgrims resting from their journeys.

Some of them incorporated covered galleries to provide relief from the heat of sun, along with space to shelter for travellers, traders, and pilgrims resting from their journeys.

The stepwell became a definitive form of public architecture, open to and used by all, a universal feature of daily life and a hive of social activity.

They were usually funded by wealthy patrons, who sought the prestige of providing such an important civic monument.

They were usually funded by wealthy patrons, who sought the prestige of providing such an important civic monument.

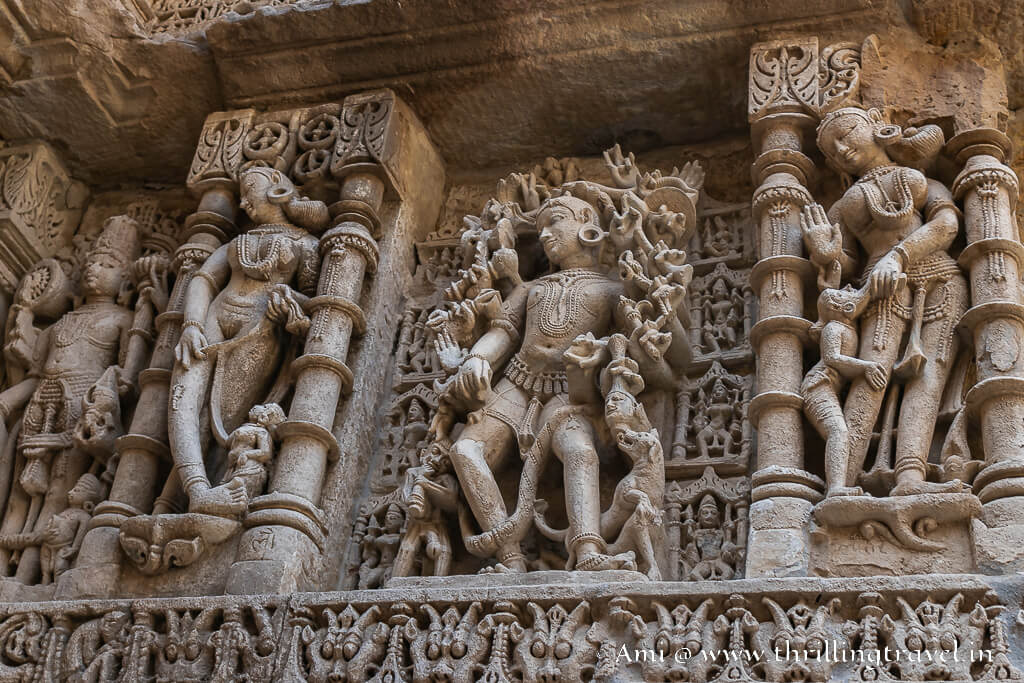

In many cases these stepwells became full-blown temples, their walls adorned with sculptures of the gods and goddesses, their columns and chambers lined with elaborate ornamentation, prayer niches, and shrines.

Sites of spiritual as well as functional and social significance.

Sites of spiritual as well as functional and social significance.

Or in the case of stepwells built by India's Islamic dynasties, where representational art (depicting humans or living creatures) was avoided, they were nonetheless decorated with sumptuous and intricate stonework.

That they were functional places did not preclude beauty.

That they were functional places did not preclude beauty.

To build a stepwell was a huge challenge; this is underground architecture, after all, fraught by the risk of collapse under pressure from the earth pushing in from either side.

And yet they stand, centuries on. Stepwells aren't only beautiful; they are triumphs of engineering.

And yet they stand, centuries on. Stepwells aren't only beautiful; they are triumphs of engineering.

This combination of factors — the necessity for providing water, the engineering challenge, the social importance, the opportunity to create something beautiful — prompted some of the most striking, unusual, and impressive architecture anywhere in the world, as at Chand Baori.

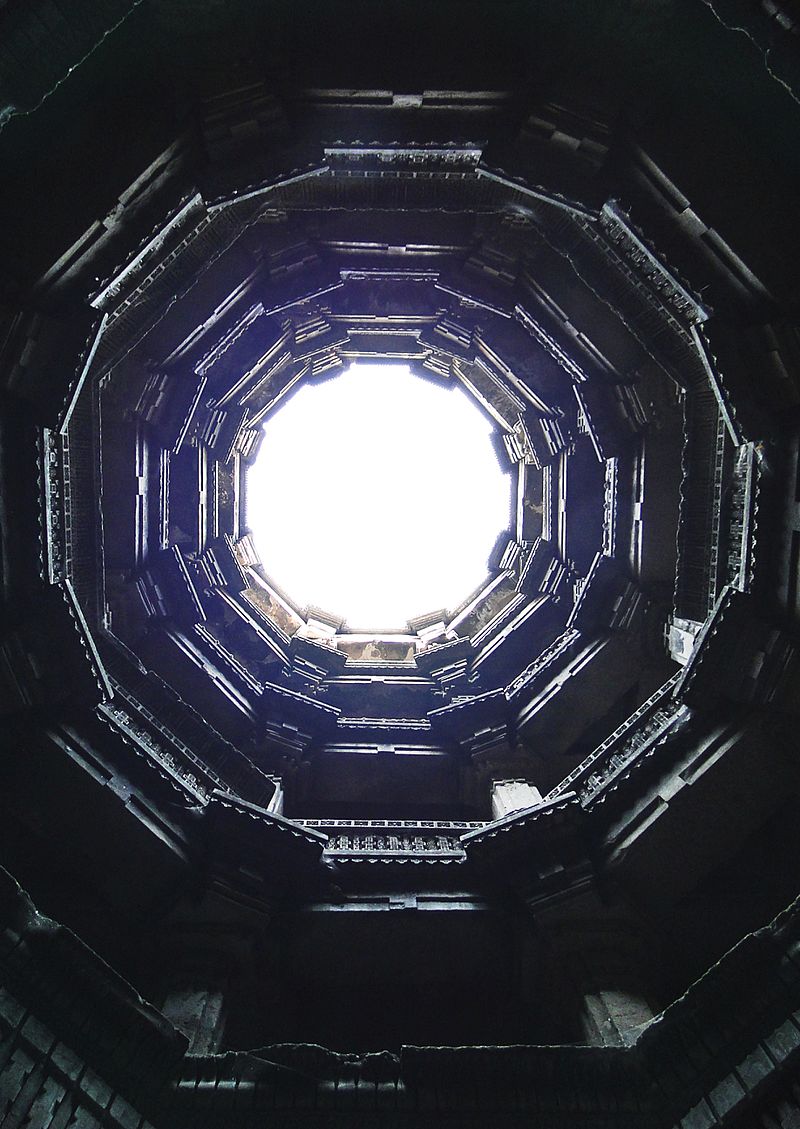

This is architecture which invites us to look *down* rather than — as with most buildings — up.

We see into the earth, as the structure opens below us; no wonder stepwells have been called inverted temples.

We see into the earth, as the structure opens below us; no wonder stepwells have been called inverted temples.

There are thousands of stepwells in India, but many of them have been lost to time, silted up and buried, collapsed, or simply forgotten.

Though indispensible for centuries, they were made obsolete by modern plumbing and water infrastructure, and thereafter abandoned.

Though indispensible for centuries, they were made obsolete by modern plumbing and water infrastructure, and thereafter abandoned.

Still, their social and spiritual importance was irreplaceable, and there are stepwells which have endured as temples and sites of worship.

Not to mention those that remain central parts of their community, whether as tourist hotspots or places for a swim!

Not to mention those that remain central parts of their community, whether as tourist hotspots or places for a swim!

There's nothing quite like the stepwells of India, a type of underground architecture which combined the vital function of providing water with masterful engineering, majestic architecture, delightful ornament, and social and spiritual purpose.

Public architecture at its finest.

Public architecture at its finest.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh