Today, a thread on how to evaluate popular military history. Just how accurate is that history book you are reading? How can we evaluate the claims that historians make? We are going to explore this through the use of of some examples, both positive and negative. 1/33

Fair warning, I am going use two authors who are much more popular than I am, as negative examples. This isn't a hit at them as writers: they are great writers. They are much better at writing than I am. It does show that we can't always be all things to all peoples. 2/33

Unlike many historical fields, military history, has a popular authorship. That is to say, people who are non-specialists (who did not obtain graduate degrees in the field they are writing in) author books that appeal to the broad audience that military history garners. 3/33

These books are well written, but contain some factual or interpretive errors. So, today, I am giving some brief guidelines that I use when evaluating a book, so that you can use your own best judgement when thinking about claims made by an author. 4/33

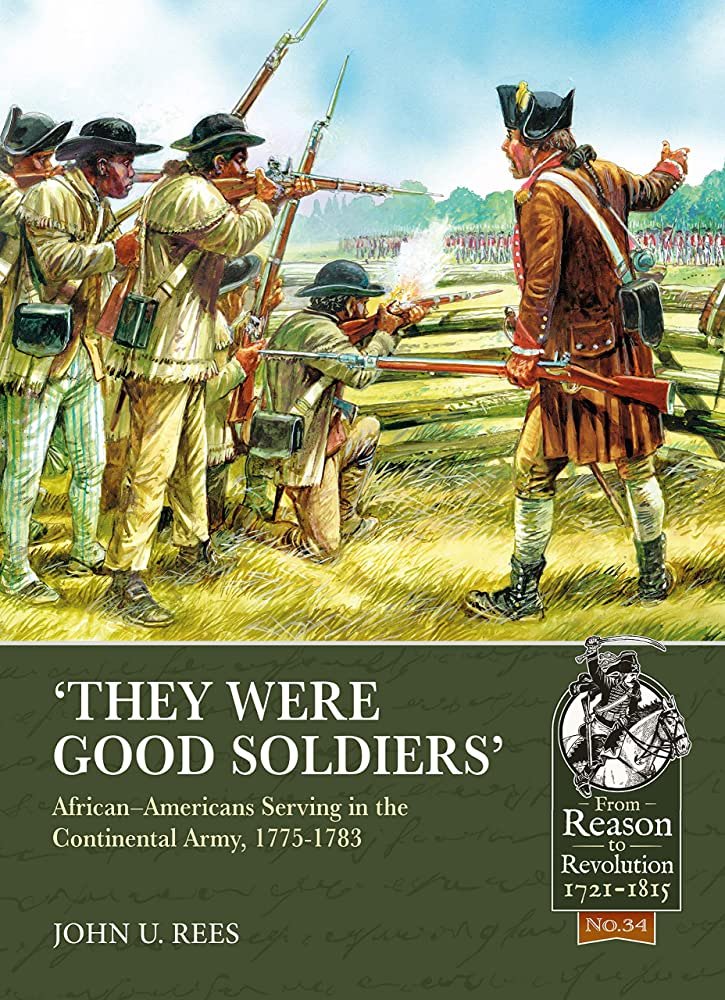

This post is not a screed against writers without Ph.Ds. I have good friends outside the academic world who not only write history, but write history well. John U. Rees, the author of They were Good Soldiers, with Helion & Co. is a perfect example of this type of author. 5/33

John has spent a life as an amateur (one who works for the love of the subject) historian, and has learned more about the Continental Army of the AWI than any specialist scholar I know. When you read John's work it is clear that he has done the necessary research. 6/33

I am increasingly concerned, however, that non-specialists make it difficult for professional historians to effectively challenge myths. In May of 2019, journalist and award-winning author Rick Atkinson gave a engaging talk at George Washington's Mount Vernon. 7/33

In a hour of speaking, Atkinson held forth knowledgably on many topics. When he turned to the subject of combat during the American War of Independence, however, he began to falter. 8/33

Atkinson asserted that, "Unlike modern war, killing is usually intimate, at very close range, face to face, often with the bayonet. That's partly because eighteenth-century muskets were mostly inaccurate beyond fifty yards and usually hopeless beyond one hundred yards." 9/33

Atkinson's stereotyping regarding eighteenth-century warfare is followed by Patrick K. O'Donnell, in his treatment of an elite Maryland regiment the Continental Army, Washington's Immortals. Like Atkinson, O'Donnell has written award-winning books on recent conflicts. 10/33

O'Donnell summarizes infantry combat in the period as follows:

"Because muskets were so inaccurate, troops practiced laying down concentrated fire in large numbers. Soldiers of the time lined up in rows, sometimes eight or ten ranks deep, and fired en masse." 11/33

"Because muskets were so inaccurate, troops practiced laying down concentrated fire in large numbers. Soldiers of the time lined up in rows, sometimes eight or ten ranks deep, and fired en masse." 11/33

O'Donnell clearly misleads the reader, as firing lines in the eighteenth-century were ranged between two and four ranks deep, and during the war he is discussing, two was the norm. In Washington's Immortals, O'Donnell does not provide a reference for this quotation above. 12/33

O'Donnell found this quote, likely in Michael Stephenson's Patriot Battles, a passable secondary work, who in turn, found it in Major General Basil Perronet Hughes 1974 work, Firepower: Weapon Effectiveness on the Battlefield, 1683-1850. 13/33

So, to review, O'Donnell has used a quote in his book, that was quoted in book from 2007, which in turn was quoting original material from 1974. In doing so, he made claims which contradict the more recent scholarly assessments (Duffy, 1987). 14/33

Now, it might seem that I am picking on Atkinson and O'Donnell, both of whom are far more well-known than I will ever be, and who are the award-winning authors of many books. They are both excellent writers, and many of their books are outstanding. 15/33

The trouble arises when these authors, who do not have formal historical training, having written many well-received books, begin to think that they can write in all periods of history with equal skill. The casual reader of military picks up paperbacks of these books. 16/33

They assume that because the author is well-known, and claims to be a historian, that they have done the necessary research and know what they are talking about. This perpetuates myths asserted when non-specialists use much older secondary works to frame their perspectives. 17/33

What I hope to do in the remainder of this post, then, is provide a checklist that the casual reader of military history can use to evaluate the abundant works of popular history which they might find at the local bookstore. 18/33

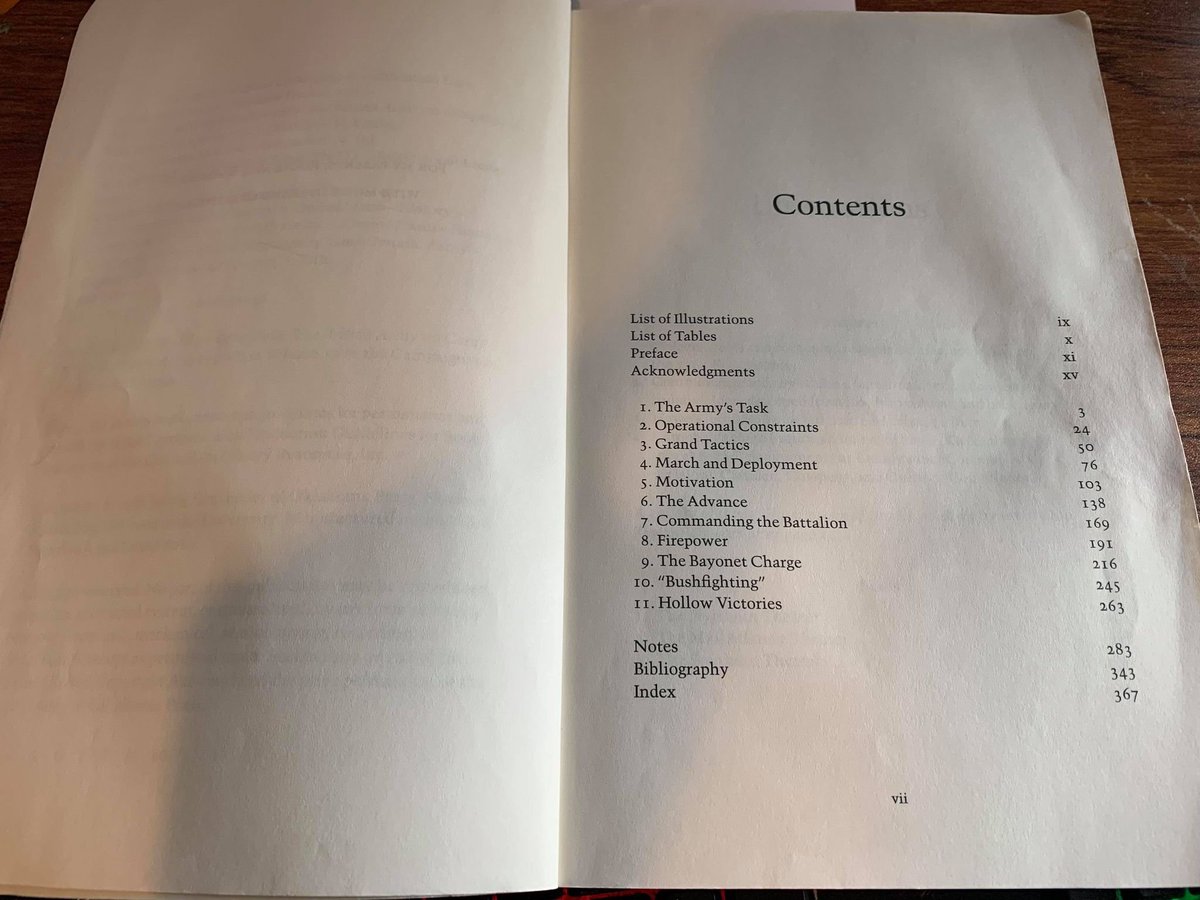

1. Survey the Contents.

A necessary first step for anyone who seeks to judge a book by more than its cover. Open the book to the "table of contents" page. Is there an endnote section, or a bibliography, or even a "suggested further readings" section? 19/33

A necessary first step for anyone who seeks to judge a book by more than its cover. Open the book to the "table of contents" page. Is there an endnote section, or a bibliography, or even a "suggested further readings" section? 19/33

If the book has all of these things, regardless of who the author is, or who the publishing house might be, it is apparent that the author has at least tried to provide an apparatus for where the reader can evaluate their claims based on evidence. 20/33

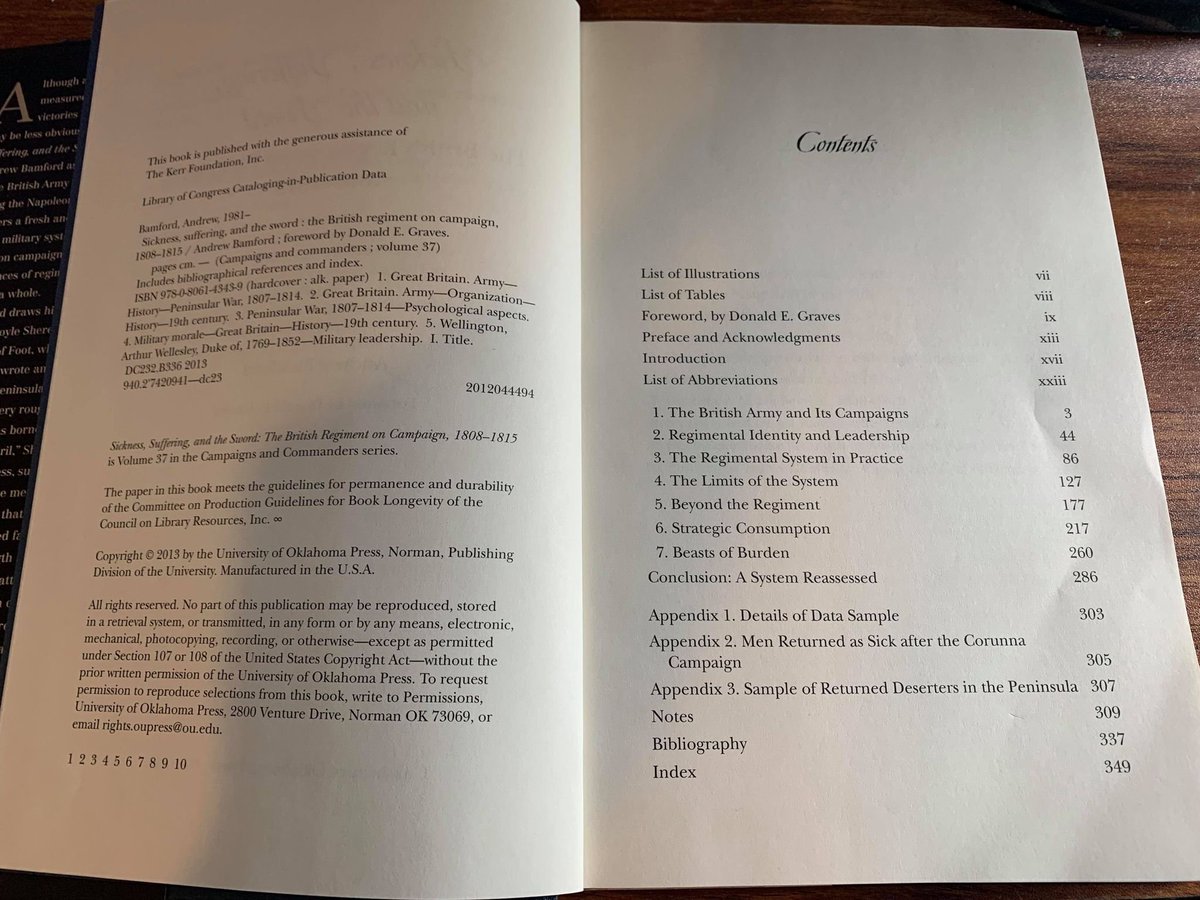

2. Look at the Publication Information

Almost all books have a page, usually opposite of the table of contents, which list of information like: Where was the book published? If it came out with a university press, it went through peer review. 21/33

Almost all books have a page, usually opposite of the table of contents, which list of information like: Where was the book published? If it came out with a university press, it went through peer review. 21/33

Peer Review: the chapters of the book have been scrubbed the author's personal information, and reviewed by multiple, other historians who specialize in this area. This is not a fool-proof answer for problems, academic historians make mistakes and can be wrong. 22/33

Secondly, look for when the book was published: books which were published, broadly, after 1960, began to be subjected to much more rigorous scholarly review and quotes and claims are more likely to be footnoted with primary-source evidence. 23/33

3. Leaf through a few pages

Starting from your place at the publication information, select four or five pages, at random, from the main chapters of the book. Examine each page. Are there quotes? Do these quotes have citations? 24/33

Starting from your place at the publication information, select four or five pages, at random, from the main chapters of the book. Examine each page. Are there quotes? Do these quotes have citations? 24/33

4. Engagement with Historiography

At this point, I am sure some of my readers' eyes are beginning to glaze over. How well an author connects with historiography, or the collected works of historical literature on a specific topic, can give you valuable information. 25/33

At this point, I am sure some of my readers' eyes are beginning to glaze over. How well an author connects with historiography, or the collected works of historical literature on a specific topic, can give you valuable information. 25/33

First of all, referencing other arguments that have been made demonstrates that the author of the book you are holding has read widely, and is not unnecessarily covering ground that other historians have already trod. 26/33

5. Examine the Bibliography or Notes

In this step, judge how much material the author has collected. Specifically, you should hope to find collections of both primary and secondary sources. Primary sources (quotations from the period being studied) are very valuable. 27/33

In this step, judge how much material the author has collected. Specifically, you should hope to find collections of both primary and secondary sources. Primary sources (quotations from the period being studied) are very valuable. 27/33

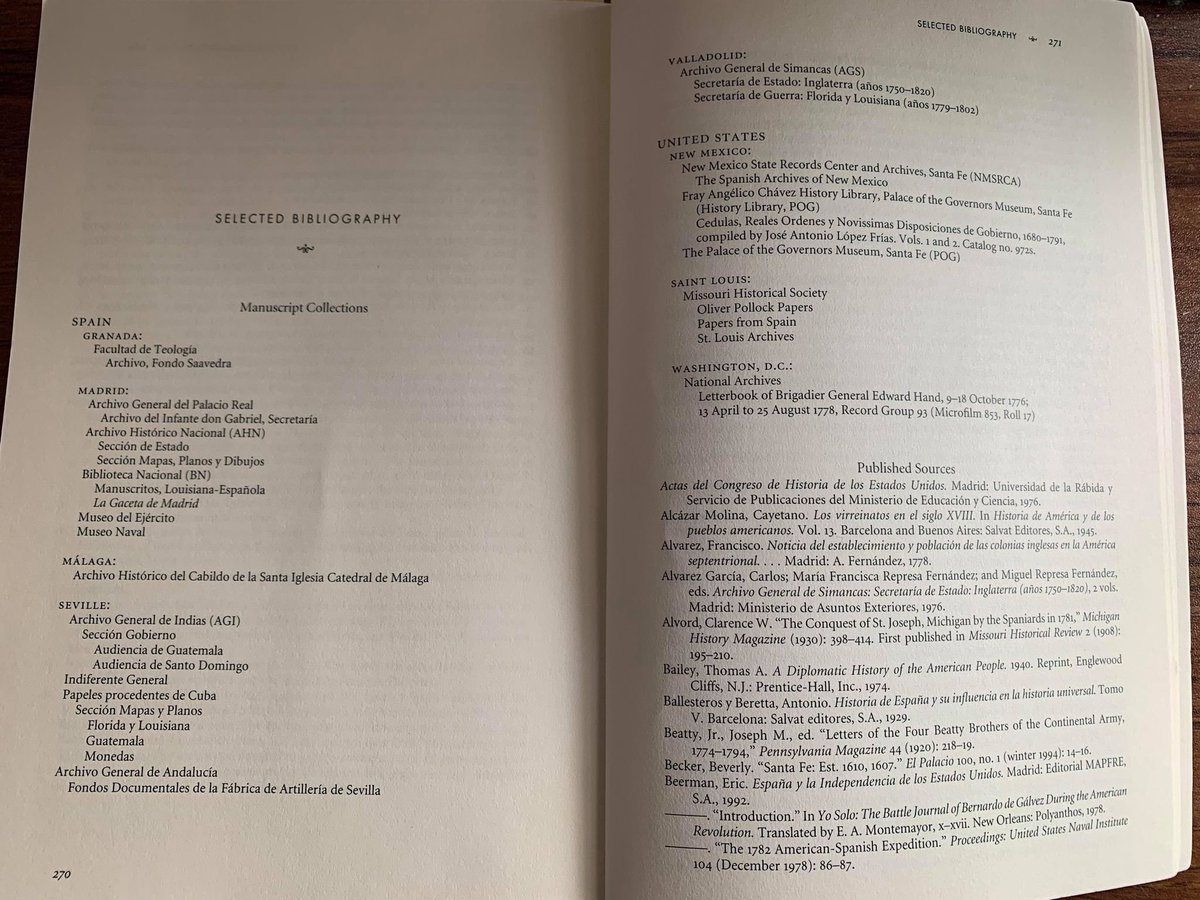

A good work of history will often list these sources separately, and even break down primary sources and secondary sources into sub-categories: Archival Material, Publish Primary Sources, Periodicals, Unpublished Dissertations, etc. 28/33

6. Think about the qualifications of the Author

By now, you will already have some sense of the level of expertise that the author has brought to bear on their subject. With that said, it may still be helpful to examine their stated qualifications. 29/33

By now, you will already have some sense of the level of expertise that the author has brought to bear on their subject. With that said, it may still be helpful to examine their stated qualifications. 29/33

Have they held a long-term interest in the topic, or have they mostly published in other fields? None of these questions should cause you to dismiss the book out of hand, which is why I place this criteria last: it is probably the least important. 30/33

Armed with this guide, I hope you have the resources necessary to evaluate the quality of your reading material, on whatever your topic may be. Historians should all be able to write their books for a wide audience, but make sure that they are supporting their claims. 31/33

Finally, please don't ask: "what is your beef with Rick/Patrick." They are both great writers, who have written incredible books on WW2 and modern conflict. 32/33

I look forward to their future books, and if they are reaching a wide audience with accurate information, no one will be more pleased than I am.

For sources, etc, you can read the thread here: kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2021/06/separa…

33/33

For sources, etc, you can read the thread here: kabinettskriege.blogspot.com/2021/06/separa…

33/33

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter