Do you ever feel that older cities are just more interesting than new ones?

Well, it isn't just because they're old.

It's because of something called "vernacular architecture"...

Well, it isn't just because they're old.

It's because of something called "vernacular architecture"...

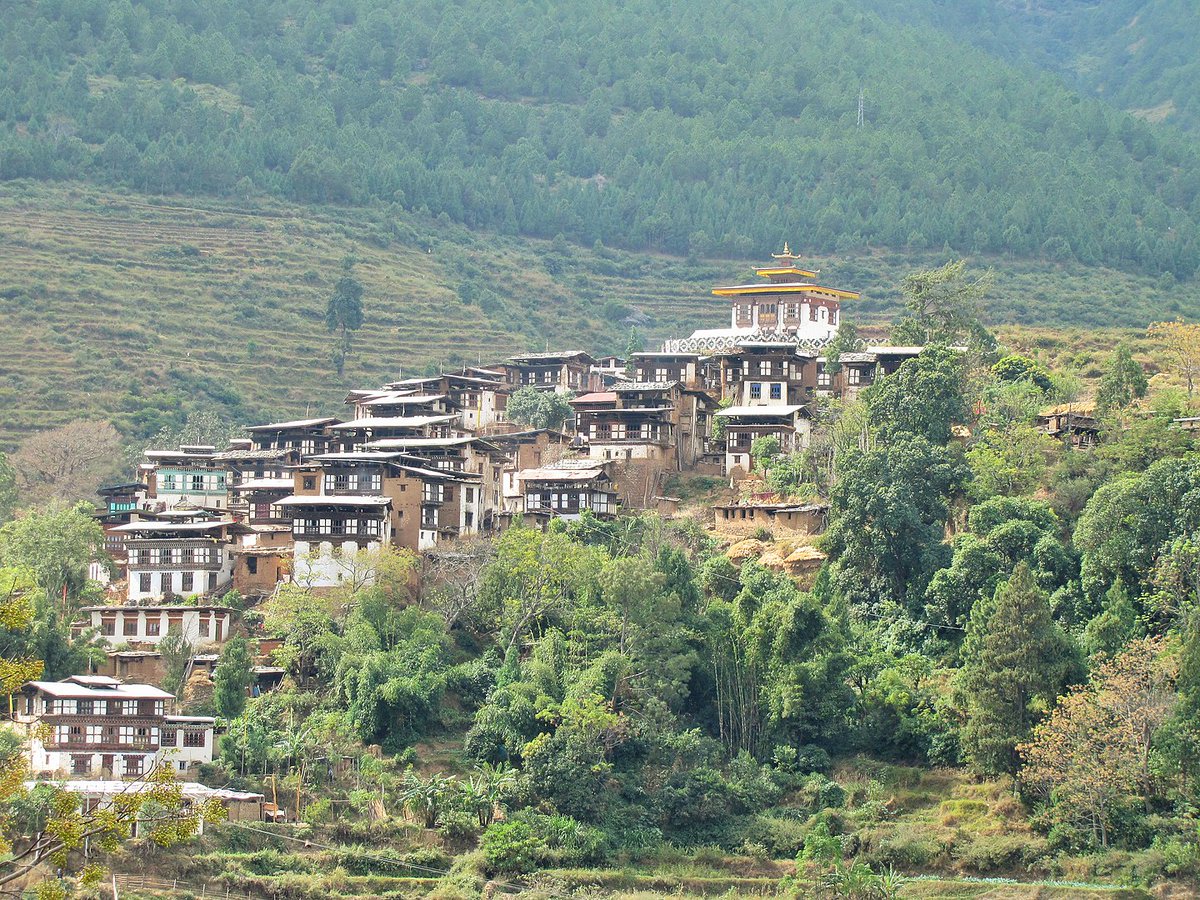

What makes the cobbled streets of York so charming? Or the jettied houses of Plovdiv? Or the terraced villages of Bhutan? Or the round tulou houses of Fujian?

The answer is vernacular. What is it? Well, vernacular clearly isn't a specific style of architecture.

The answer is vernacular. What is it? Well, vernacular clearly isn't a specific style of architecture.

Before industrial mass-production, rigorous town planning, bureaucratised building regulations, architecture schools, and engineering degrees...

...things were built according to local needs and constraints and traditions, using locally available materials.

...things were built according to local needs and constraints and traditions, using locally available materials.

So vernacular is a *way* of building.

And it's how most things were built for most of history, all around the world.

Whether Shibam in Yemen or Dinan in France, both were built without architects and engineers who were "professional" in the modern sense.

And it's how most things were built for most of history, all around the world.

Whether Shibam in Yemen or Dinan in France, both were built without architects and engineers who were "professional" in the modern sense.

But how did focus on need (function) and available building materials (convenience/cost) make these old places all look so different?

Such principles also underpin most modern construction, and yet cities around the world look more similar than ever.

Such principles also underpin most modern construction, and yet cities around the world look more similar than ever.

There's a few key differences. One is that "available building materials" used to mean something very different.

Whereas now steel and concrete and glass are globally available and ubiquitous construction materials, that wasn't the case in the past.

Whereas now steel and concrete and glass are globally available and ubiquitous construction materials, that wasn't the case in the past.

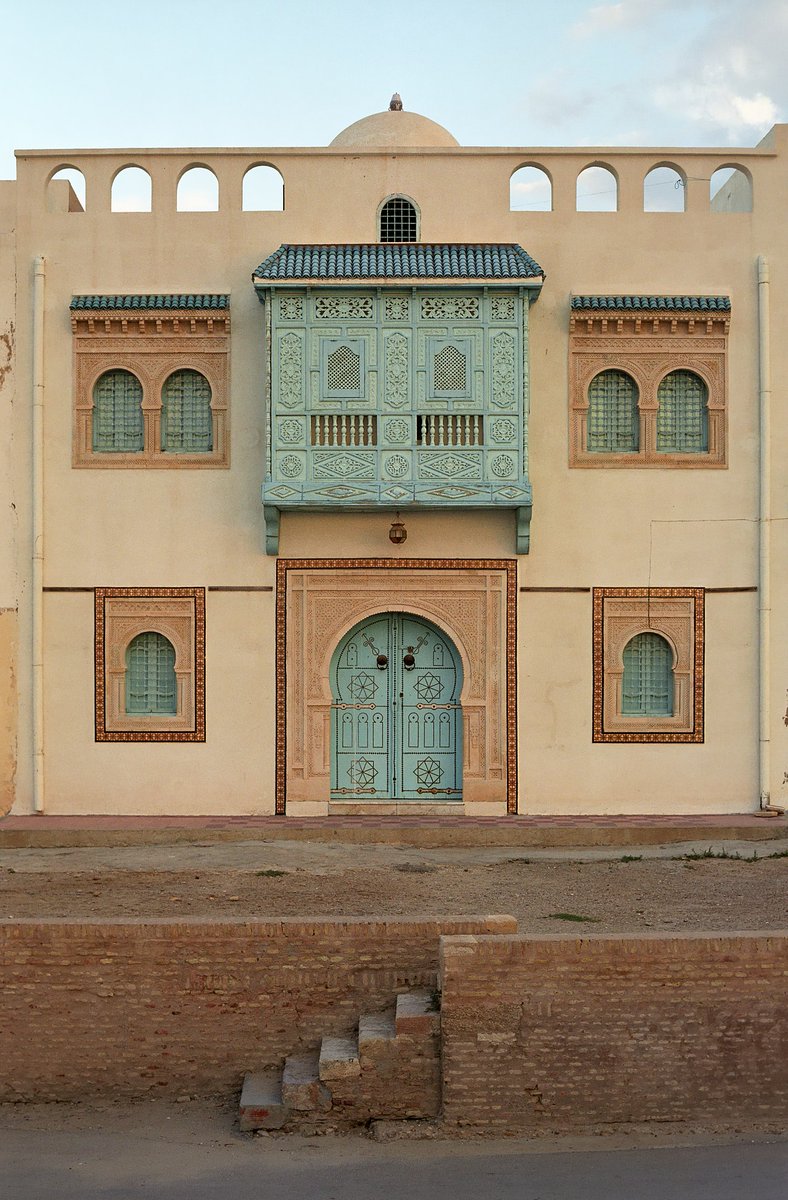

People used whatever they could, be it marble, bamboo, limestone, pine, mudbricks, slate, turf, oak, clay, reeds...

What was available as a construction material varied from region to region, hence a natural variety in regional architectures.

What was available as a construction material varied from region to region, hence a natural variety in regional architectures.

Another difference is that less globalised (and less nationalised) cultures tend to produce highly localised, more divergent styles.

How the problem of needs versus resources was solved differed immensely from region to region, simply because they were less interconnected.

How the problem of needs versus resources was solved differed immensely from region to region, simply because they were less interconnected.

And that's why traditional architecture varies so wildly.

Each region and culture found its own way of doing things, according to local needs, traditions, and constraints.

Hence why you can (often) tell which region or country you're in simply by its buildings.

Each region and culture found its own way of doing things, according to local needs, traditions, and constraints.

Hence why you can (often) tell which region or country you're in simply by its buildings.

This sort of carefully tuned regionalism doesn't explain everything, however.

Another important factor is that there weren't as many government-imposed restrictions on how houses should be built or towns should be planned.

People just got on with it...

Another important factor is that there weren't as many government-imposed restrictions on how houses should be built or towns should be planned.

People just got on with it...

...thus producing the opposite of a planned town with homogenised architecture and standardised streets.

When lots of people do lots of different things with relatively little oversight over the course of several decades or centuries, the result is a street layout like this.

When lots of people do lots of different things with relatively little oversight over the course of several decades or centuries, the result is a street layout like this.

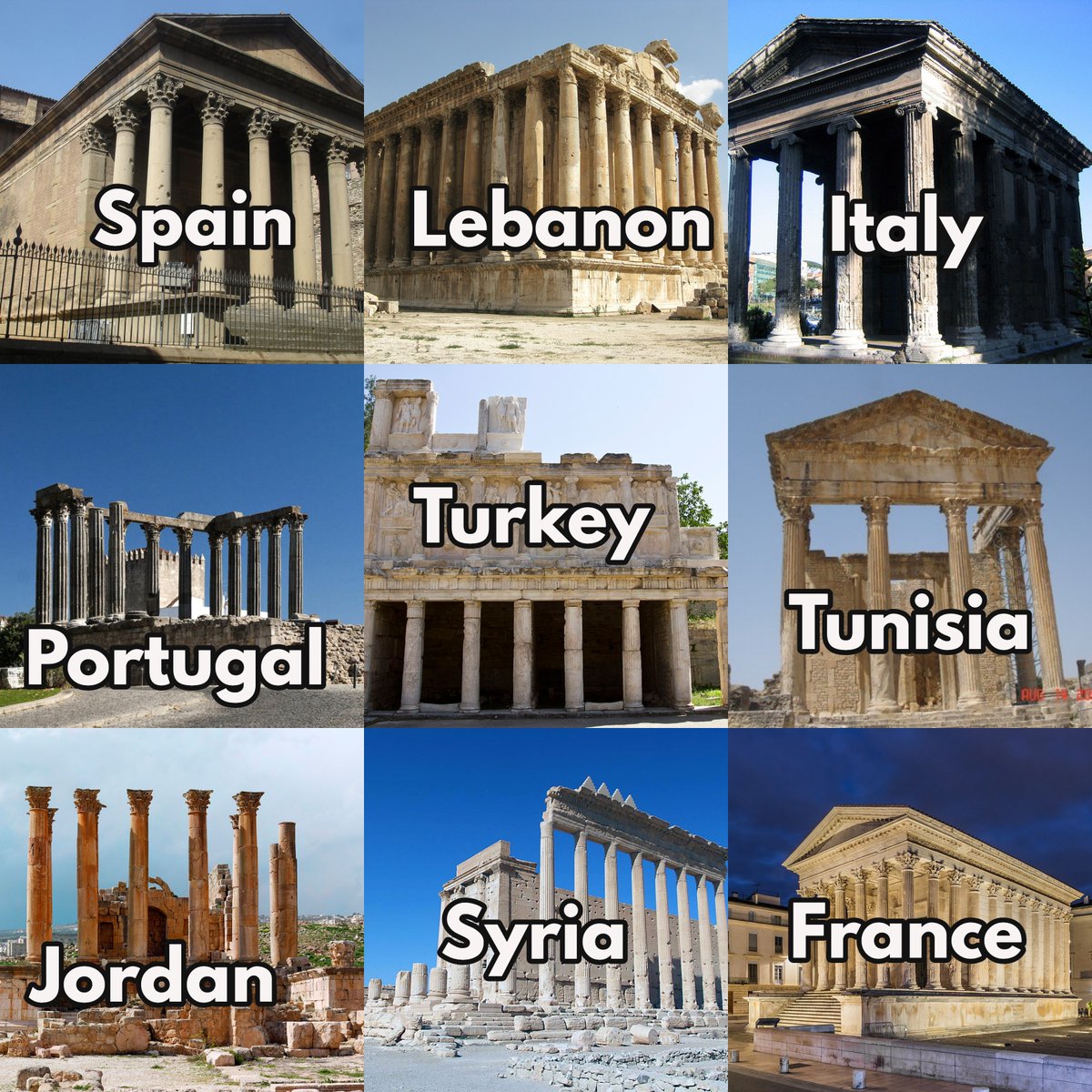

Then again, though the grid plan seems like a modern invention, it is actually thousands of years old.

From Mesopotamia to China to Mesoamerica, cities have been laid out on grids since the start of human civilisation.

Regulations or town plans are not new.

From Mesopotamia to China to Mesoamerica, cities have been laid out on grids since the start of human civilisation.

Regulations or town plans are not new.

Just consider Ancient Rome, which took its grid-based urban planning and strict architectural style wherever it went, from Britain to Algeria to Jordan, and everywhere in between.

This might be "traditional" in some sense, but it isn't really vernacular.

This might be "traditional" in some sense, but it isn't really vernacular.

Something like Le Corbusier's speculative Plan Voisin for Paris, or even the endless rows of cookie-cutter houses in suburbs, are a result of the same thinking behind Ancient Roman urban planning.

Vernacular, meanwhile, encourages variety and diversity — it's more interesting.

Vernacular, meanwhile, encourages variety and diversity — it's more interesting.

Strict town plans and building regulations are useful and important — they help with things like transport or sanitation, and mitigate against risks like flooding or fire.

But, imposed too strictly, they mean it is now illegal to build something like France's Mont Saint-Michel.

But, imposed too strictly, they mean it is now illegal to build something like France's Mont Saint-Michel.

So vernacular architecture results in regionally and culturally specific styles of building. It's why different countries and places... look different.

And it's part of why we are so drawn to older places, and why tourists flock to every town with the slightest bit of history.

And it's part of why we are so drawn to older places, and why tourists flock to every town with the slightest bit of history.

Because, unlike places with globally standardised architectural styles and overly strict town planning, the older, vernacular places speak to their history, region, and culture.

And, by virtue of being less planned, they are filled with personality, character, and charm.

And, by virtue of being less planned, they are filled with personality, character, and charm.

Vernacular architecture also tends to be more human-scale as a direct result of how it was built.

Such places are therefore often more suited to social integration and to community, to healthier and happier lifestyles, and all the other benefits of human-scale design.

Such places are therefore often more suited to social integration and to community, to healthier and happier lifestyles, and all the other benefits of human-scale design.

Not to mention that vernacular architecture is much more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

Long before climate control, people figured out how to make buildings cool in summer and warm in winter — and they did it by using local materials, rather than importing them.

Long before climate control, people figured out how to make buildings cool in summer and warm in winter — and they did it by using local materials, rather than importing them.

Insensitivity to local climate, ecological unsustainability, designed for cars rather than communities, badly scaled for human beings, bland and uniform aesthetics...

These are just some of the problems of modern urban design which the vernacular might help us solve.

These are just some of the problems of modern urban design which the vernacular might help us solve.

I've written about vernacular architecture before — from Shibam to Plovdiv — in my free, weekly newsletter.

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider joining 80k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider joining 80k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh